This line from a paper a few years back by Edella Schlager and Tanya Heikkila may seem obvious, but in the context of current discussions over the future of Colorado River management, it bears repeating:

A water allocation rule that allocates more water than is available in a river is not well matched to its setting.

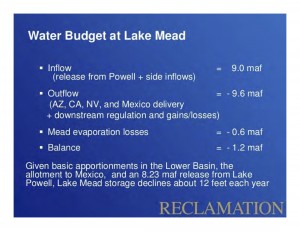

Yup. That in a nutshell is the problem highlighted by this oft-revisited Bureau of Reclamation slide demonstrating how the Lower Colorado River Basin’s water budget works. Everyone here is following the rules, living within their legal allocation, and Lake Mead keeps dropping because the Law of the River has allocated more water than is available in the river.

This is the critical thing to understand as we see the beginnings of the new “Colorado River System Conservation Program” taking shape, which would create a framework to pay farmers to leave water in the river. It’s not enough to simply save water. The way we go about it must be embedded within, and take into account, the rules governing allocation and distributions of Colorado River water.

Jim Lochhead, now head of Denver Water, wrote an excellent introduction to the problem a decade ago in a remarkably candid history of the Colorado River water wars of 1990-2003 (paywalled). In the early ’90s, it was clear that overuse was an increasing problem. The overuse then came in the form of California’s dependence on surplus that other states had not been using. Nominally, California’s allocation of Colorado River water was supposed to be 4.4 million acre feet of water per year, but since the 1950s, it had been dining on surplus left unused by other states. With Las Vegas’s growth and Arizona’s completion of the Central Arizona Project, the surplus was disappearing, and California had to figure out a way to get from the 5-plus maf it had been using most years down to 4.4 maf.

Imperial Valley ag still thrives despite drought and cutbacks in delivery of Colorado River water to California

In the decade since that time, Southern California has been remarkably successful at making the adjustment. Coastal Southern California’s economy is still as robust as ever, even in the face of the current drought, and the Coachella-Imperial-Palo Verde farm belt is still thriving with big ag. The details of how they did it – the largest ag->urban water transfer in history – are interesting (buy my book! as soon as I finish writing it!). But a critical necessary condition, before the details of fallowing and ag efficiency were worked out, was the need for a change in the “water allocation rules” that Schlager and Heikkila are talking about. The water wars of 1990-2003 that Lochhead writes about were all about the basin states and the federal government realizing the water allocation rules were inadequate. One could argue that the “structural deficit” was in a sense even larger then, and that first round of action was about reducing it.

When you look at the size of the current structural deficit in that Bureau slide above – 1.2 million acre feet per year – the Colorado River System Conservation Program looks modest indeed. We’re likely to see more details as the agreements are finalized over the next week, but at the going price of water, the $11 million effort looks like enough money to generate 75,000 to 100,000 acre feet of water savings. It sounds like most of the initial attention will be initially be focused on the Lower Basin, with Reclamation hoping to issue “requests for proposals” this year to farmers interested in fallowing land for a price per acre foot of water yet to be determined. With Palo Verde, Coachella and Imperial all actively engaged in the already existing California ag->urban transfer programs, much of the action is likely to be on the Arizona side, especially Yuma and Wellton-Mohawk (though I’ve also heard mention of some possible interest across the river with the Bard Irrigation District, which is on the California side of the border but gets Yuma Project water).

When I asked recently whether 75k – 100k acre feet was enough, given a structural deficit an order of magnitude larger, one of the people working on the program pointed out that this is a pilot program, to learn how to do it, then added, “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.”

The 1990-2003 experience suggests that the water conservation piece of this may be the easy part. As a nice new Western Resource Advocates white paper explains, we know how to conserve the water. The key piece here, and the reason the System Conservation Program is so interesting and important, is that we need to get the water allocation rules and river management policies right in order to cause those conservation savings to happen.

Pingback: Eating the #ColoradoRiver shortage elephant, one bite at a time — John Fleck | Coyote Gulch

Pingback: Blog round-up: Groundwater and the public trust doctrine, California style; why the response to drought has been so weak, our thirsty lawns, and more … » MAVEN'S NOTEBOOK | MAVEN'S NOTEBOOK