By Eric Kuhn

As the states of the Upper Colorado River Basin work through how to build a “demand management” account in their reservoirs to protect against shortages, water from retiring coal plants could play a crucial role. With few alternatives for use of the water, simply banking it in Upper Basin reservoirs is an attractive option.

In a recent KUNC piece, Luke Runyan discussed the impact of Tri-State G & T’s decision to close its coal-fired power plant near Craig, Colorado. Luke focused on the impact of the closing on the local community and options for the water rights that will be freed up when the plant is closed. The Craig Station is one of ten major coal-fired power stations that were built in the Upper Colorado River Basin from the mid-1960s through the early 1980s. Several smaller plants were also built in the 50s, now all shut down. These plants were spaced throughout the basin with three in Utah, two each in Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico, and one in Arizona’s small portion of the Upper Basin, the Navajo Generating Station near Page, AZ.

For many reasons – their age (most are approaching their design life), high operational costs, and the need to reduce carbon emissions – these plants are being de-commissioned. In 2014, three of the five units of the San Juan Plant in Northwestern New Mexico were shuttered followed by two of the four units of the neighboring Four Corners Plant in 2017. Last year, the Navajo Generating Station produced its last power and Tri-State made the decision to completely close the Craig Station by 2030. Further, last year the owners of the remaining operational units of the Four Corners and San Juan Plants in New Mexico and the Naughton and Bridger Plants in Wyoming made it clear that each will be shut down sometime in the next decade or so. By the early 2030s it’s likely that there will be no operating coal plants in the Upper Basin (the possible exception being one of the plants in Utah). This raises the question explored by Luke Runyon. What will happen to the water that these plants were once consuming?

The source of cooling water for all these plants is the Upper Colorado River or one of its tributaries. According to the Bureau of Reclamation’s Consumptive Uses and Losses Report, their 1991-2018 annual consumption averaged 162,000 acre-feet per year. At the peak in 2006, these plants were collectively consuming over 170,000 acre-feet of the Upper Basin’s compact share. In 2018, it had fallen to 144,000 acre-feet. Recognizing that the total consumptive use in the Upper Basin is a bit over four million acre-feet per year (not counting CRSP reservoir evaporation), a reduction of 4% may not seem like a big deal, but a closer look suggests that it could be very significant.

Upper Basin use

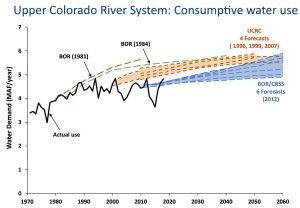

First, the Upper Basin’s total annual consumptives use have been flat since the late 1980s (see this nice analysis by Jian Wang and David Rosenberg at Utah State). The reasons are simple. The last major irrigation and export projects (trans-mountain diversions) were largely completed by the mid-1980s. Except for the Lake Powell Pipeline (which may not be considered an Upper Basin use under the compact), there are no serious proposals for new export or irrigation projects (Denver Water’s Moffat Expansion and Northern Water’s Windy Gap Firming Project are tweaks to existing projects). Some have suggested the plant water could be sold or made available to existing export or irrigation projects. That is very unlikely. The diversion points for the existing trans-mountain diversions are far from the locations of these plants. Moving plant water to the Continental or Great Basin Divides would be very expensive. The non-use of the plant water rights could in some years benefit existing irrigation supplies, but for the most part irrigation users already have senior rights and the irrigation of new lands would require large new public subsidies, an unlikely event. Further, much of the internal municipal growth within the Upper Basin is displacing existing irrigated agriculture where the net change in consumptive use is small or even negative. Since it’s subject to the vagaries of regional precipitation and water supply conditions in adjacent basins such as the South Platte where water is exported to, consumptive uses in the Upper Basin will continue to be variable on a year-to-year basis, but it is clear that the loss of 160,000 acre-feet of consumptive use over the next decade will be measurable and will likely contribute to a downward trend.

Second, 160,000 acre-feet of consumptive use per year is actually a lot of water. Only a few of the Upper Basin’s largest projects, the C-BT and Uncompahgre Projects for example, consume more. Water efficient cities such as Las Vegas or Phoenix could serve more than 1.5 million people with this amount of water. It’s over half of Nevada’s use from Lake Mead and close to half of the average annual use of the upper states of New Mexico and Wyoming. Between equalization releases (the last one was 2011), Lake Powell has “memory.” It stores every extra acre-foot of inflow. Without the coal plant use, an additional 1.4 million acre-feet of post-2011 water would be in storage there today.

Finally, for the implementation of the drought contingency plans (DCPs), 160,000 acre-feet of water could be a very useful and significant asset. The States of the Upper Division are currently studying the implementation of demand management. The federal legislation approving the DCPs gives these states access to 500,000 acre-feet of Lake Powell storage space. A strategy to fill this space with 100,000 acre-feet of conserved consumptive use per year (primarily from existing agriculture) over five years would be a huge political challenge and cost $25 million per year or more. The 160,000 acre-feet of unused plant water would fill that same space in about three years. The challenges for the upper states will be first to take a realistic look at their future demands and factor in both the upward and downward trends, and to figure out how to incorporate these plant closures into their post-2026 river management strategy. If they can’t, gravity will ensure that the Lower Basin is the ultimate water beneficiary of the closing of these plants.

Another net zero gain with what UT and CO plan to extract.

Pingback: CRWCD News Drop 3/5 - Colorado River District

Pingback: Yes, there is good news in dark times: A water dividend for the Colorado River as coal plants close