DALL-E thinks we need a very large table for this, suggesting a broad need for “collective agency” to go along with our “collective action”.

The news out of last week’s Colorado River Water Users Association is that, behind the scenes, a deal is taking shape with the potential to bring Colorado River Basin water use into balance with water supply.

The deal would eliminate the “structural deficit”, and creates a framework for a compromise over the Upper Basin’s Lee Ferry delivery/non-depletion obligation.

This is huge. But so are the caveats – in terms of both the challenges remaining for a deal, and the definition of the problem we are trying to solve.

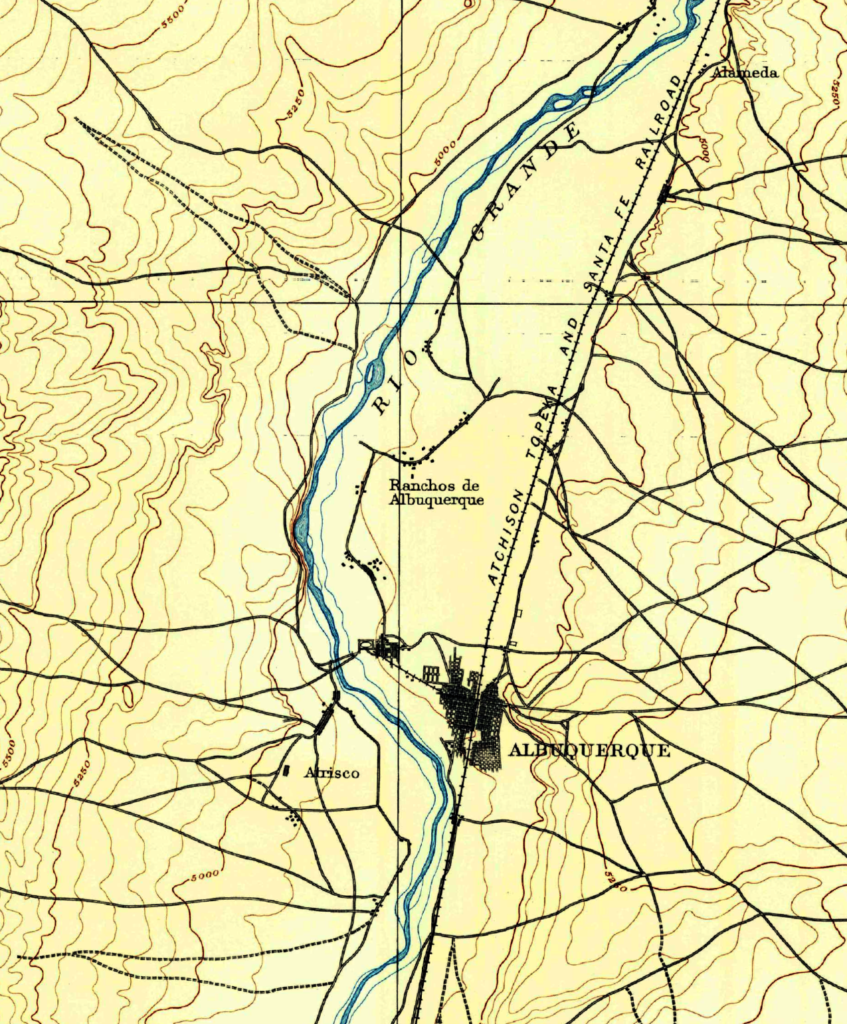

The U.S. Lower Basin states – California, Arizona, and Nevada – have converged on a set of numbers to permanently reduce their use on a year-in, year-out basis by a minimum of 1.25 million acre feet per year, eliminating the “structural deficit” – the year-in, year-out gap between inflows and outflows that has drained Lake Mead over the last two decades.

California and Arizona seem to have found a path to a compromise (the details of which have not been made public) after the early-2023 cage match that seemed to place us on the path to interstate litigation, with six states arguing for sharing the pain and California insisting on a priority administration that would have largely placed the burden of the impact of climate change on Arizona.

If separate negotiations with Mexico lead to additional reductions south of the border (which is how this has played out in the last two rounds of basin scheming), total durable, permanent Lower Basin reductions on the order of 1.5 million acre feet a year appear to be within reach.

If more cuts than that are needed to balance the system, the Lower Basin states at CRWUA made it pointedly, publicly clear that they are asking the Upper Basin states to share in the additional pain.

Implicit in that final point is the opportunity for a version of what we used to call the “Grand Bargain” – a Lower Basin concession that the river’s flow may not be sufficient to deliver 82.5 million acre feet per year. That would require even deeper cuts in the Lower Basin. To avoid interstate litigation over a Colorado River Compact delivery shortfall, the Lower Basin is offering a “Modest Bargain” of a sort – an Upper Basin contribution of water matching in some way (it’s not clear in what proportion to the additional Lower Basin cuts) in return for the Lower Basin not wading into a legal fight over the meaning of Article III(d) of the Colorado River Compact.

To the extent that this moves from the meeting rooms and hallway conversations of CRWUA to public view, the seven states need to come together on something that can be put down in writing, publicly, by (I think) March in order for the Bureau of Reclamation wizards to begin the modeling work. So this is on a very fast track.

This is a very big deal, and very good news. But….

Some terms and conditions may apply

There are a bunch of caveats.

The final AZ-CA-NV split of the 1.25-ish million acre feet is not fixed, but it is close, converging on a set of numbers that make sense, respecting some of California’s senior priority status, but not insisting on it as thoroughly as the state’s proposal of last February.

Suffice to say that the remarkable Lower Basin use numbers this year – currently at 5.8 million acre feet for the three U.S. states, the lowest total U.S. draw on Lake Mead since the modern record-keeping regime began in 1964 – shows that cuts like this are totally doable without wrecking the economies of the three states.

If we don’t have three-state numbers yet, we’re a lot farther from figuring out how each of the three states will divvy up the cuts among their users. This will be hard. Well for two of the states, anyway, Nevada just has one major user to do the divvying.

But will voluntary cuts of the scale needed be possible without the big inflow of federal cash that has helped so much this year? The precedent set by all the money sloshing around the Lower Basin right now poses a challenge.

And what of the Upper Basin’s relentless “it’s a Lower Basin over-use problem!” rhetoric over the last year. Now that the Lower Basin folks have basically said “Yup, and here’s what we’re gonna do about that”, have the Upper Basin folks painted themselves into a corner that makes the broader compromise needed on the next steps that much harder?

Who’s at the table right now?

All of this is predicated on a narrow definition of the problem we are trying to solve, which is basically a mass balance problem – figuring out how to match our use of water with the supply available, rather than over-using and draining the reservoirs. This is important! But it’s not the only thing.

This is a process dominated by the economically and politically powerful current water users. If we have a collective action problem here, we also have a “collective agency” problem. It is a system under which “agency” – the power to influence outcomes – is tightly controlled and narrowly distributed.

What about interests other than the big water agencies and their representatives in state government? This is clearly a state-to-state conversation right now, heading toward a desire for a seven-state proposal come March. In the last two rounds of this – the 2007 Interim Guidelines and the Drought Contingency Plan – the states’ proposals have carried the day.

What about the Colorado River Basin’s 30 Tribal Sovereigns? It’s not clear to me how their needs and interests are being incorporated into this process. In this regard, one is reminded of Neil Gorsuch’s dissent in this year’s Navajo decision, where he analogized to the tribe standing in line after line again and again at the DMV, only to be told that this isn’t the right line. Then which is?

What about non-water-consuming environmental values, which have similarly had a hard time figuring out which process might be the right one? The states could, in theory, act on behalf of those non-water agency interests in the deal they’re so furiously negotiating. Will they? Will the federal government step in and insist if the states don’t?

There was hope as we headed into the negotiation of the post-2026 river management regime that broader interests and values would be represented. It will be interesting to see what else beyond a seven-state proposal gets consideration in the discussions to come.

A note on sources and methods: I spent last week resting, looking at art, watching falling snow, reading a book (actually several), and not going to CRWUA. My deep thanks to my many friends who attended and filled me in what they heard and saw. All errors are mine. (Also, is that a Cocker Spaniel in the picture, a couple of seats to the chair’s left?)