For better or worse, my decision to not pay the $15 a day for an internet connection at Caeser’s Palace has left me with a bow wave of things to write about after a week spent in an around the Colorado River Water Users Association’s annual meeting in Las Vegas, NV.

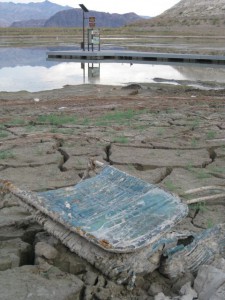

Let’s start with Lake Mead itself, which hovers over Las Vegas like a reminder of trouble to come. But hey, the reservoir’s up this year, what’s not to like? Lissa and I drove the scenic road past the marinas on Mead’s western shore, the Las Vegas playground that was not so playground-y when I was there a year ago. At Boulder Harbor this year, I found a couple of guys fishing off the boat landing that a year ago was mired in mud. The striped bass were biting, and they looked big and tasty.

Thanks to an epic snowpack, the reservoir is up more than 40 feet from where it was when I visited in October 2010 trying to document its drop to historic low levels. There were places where the shoreline was unrecognizable. But at the risk of sounding like a broken record, a close look at the data offers a reminder of the underlying problem. The Law of the River seems to ensure that the Lower Basin states are guaranteed 8.23 million acre feet a year of water released from Glen Canyon Dam. In the water year just completed, the US Bureau of Reclamation released 12.5 maf – 4.3 million acre feet of “bonus water” above and beyond what one might consider the system’s reliable yield. But Mead ended the water year up just 2.9 million acre feet. Some of the 2010-11 bonus water has already been used.

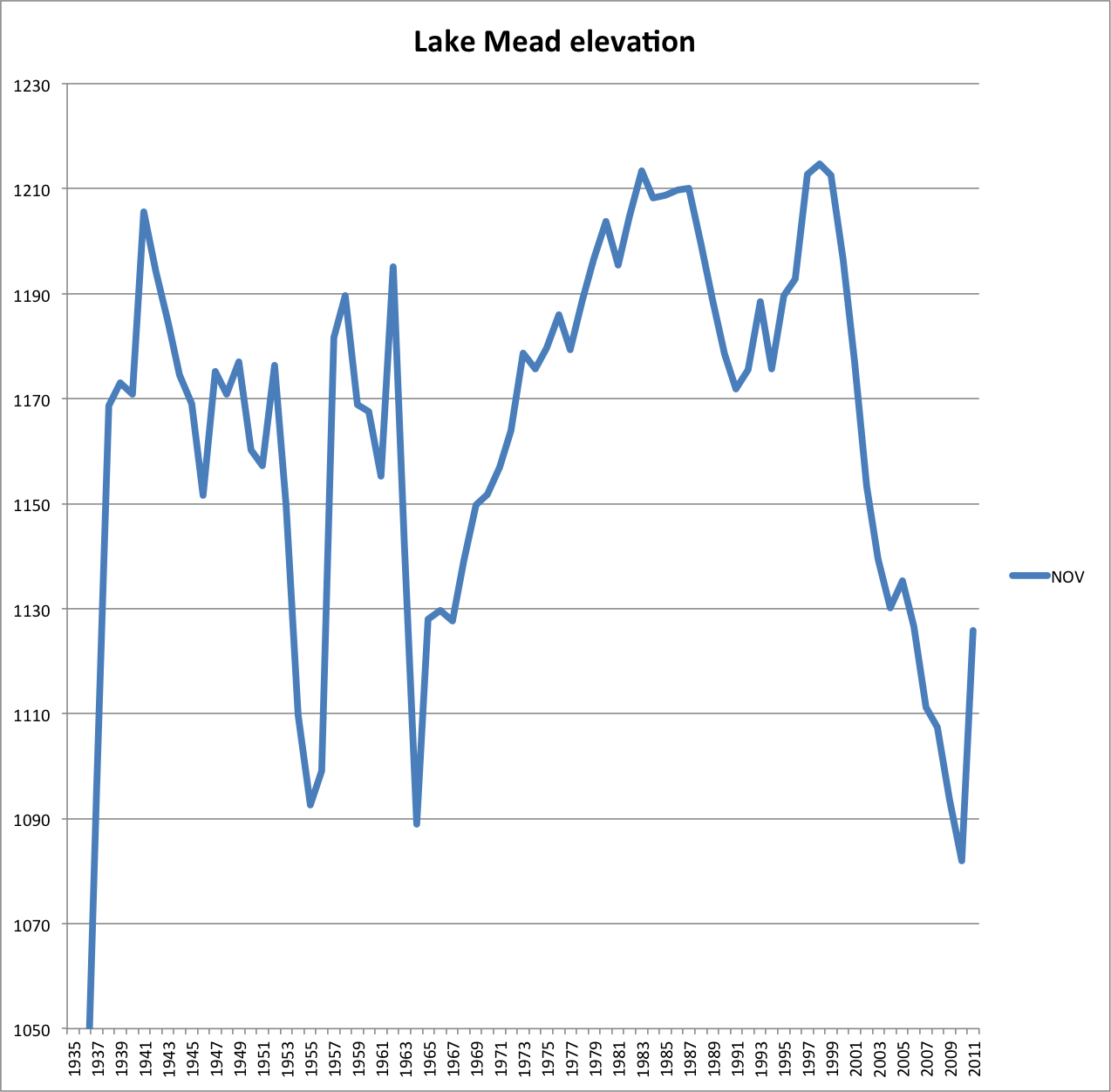

Consider the long term elevation of Lake Mead.

The big long decline you see in the reservoir’s surface elevation, beginning in 2000, coincides with a period during with the full Law of the River release from Lake Mead, 8.23 maf, happened every single year. All it takes is three or four years of such minimally required releases – either because of drought in the Upper Basin, or because the Upper Basin states’ increasing consumption of water they’re legally entitled to but are not currently putting to use, to wipe out this year’s bounty.

In a sense, the Lower Basin’s drought is a situation of its own making.