The latest monthly Colorado River water management report from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (pdf) takes a major step toward the river’s first ever shortage declaration. We’ll know more in a month, but the preliminary estimates now show drops in the level of Lake Powell by the end of this year could trigger provisions of a six year old shortage sharing agreement among the seven Colorado River Basin states that allow a reduction in releases in the 2013-14 water year from Powell, the reservoir spanning the Arizona-Utah border. That, in turn, would mean less water downstream for Lake Mead, which significantly increases the odds of reduced water availability for Arizona and Nevada in the 2015-16 time frame.

Got all that?

This is a classic example of the sort of institutional plumbing that drives water management on the Colorado River. We mostly talk about the physical plumbing – Hoover and Glen Canyon Dam, the Colorado River Aqueduct, the All-American Canal and the like. But the institutional plumbing – the nested set of principles and agreements, compacts, laws and court decisions established over the years collectively known as the “Law of the River” that governs who gets how much water, and when – is equally important, if not more so.

The key piece of institutional plumbing in the coming shortage discussions is the Colorado River Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead, often called the “2007 shortage sharing agreement”. It’s Byzantine, with complex tables of “if Lake Powell’s got x water in it and Lake Mead’s got y water in it, do z” kinds of directives for managing the system. I can’t begin to give a full explanation of the details here, but it’s important to highlight a central feature: Everyone agreed to this. This is not a case of the federal government imposing a water management scheme on the states, or someone suing and persuading a judge to impose the rules. It was the product of negotiation, a collective recognition on the part of each state (and the federal government) that a deal that provided some certainty, even unpleasant certainty, was better than the previous uncertainty over what would happen in a shortage, and the downside risk of losing a legal fight at that point. This is the users of a common pool resource developing the institutional arrangements to collectively manage that resource.

With that as a preface, here’s a timeline of what happens next:

- August 2013: The Bureau of Reclamation makes its best estimate of how much water Lake Powell will have as of Jan. 1, 2014. That estimate is based on the monthly runoff forecasts and normal releases – 8.23 million acre feet of water released from Powell over the Oct. 1 2013-Sept. 30 2014 water year for use in California, Arizona and Nevada. If inflows are low, and those normal release rates would drop Lake Powell’s surface elevation below 3,575 feet above sea level come Jan. 1, 2014, that would trigger a provision under which water is held back in Powell, reducing releases for use in California, Arizona and Nevada. Instead of 8.23 million acre feet, the Bureau of Reclamation would release only 7.48 million acre feet in the 2013-14 water year. It’s called the “Mid-Elevation Release Tier”. The shortage sharing agreement calls for such a decision to be made in August. The preliminary numbers released last week include an estimate of 3,574.97 come Jan. 1. “Based on analysis of a range of inflow scenarios,” the latest Bureau report concludes, “the current probability of realizing an inflow volume that would result in the Mid-Elevation Release Tier in 2014 is slightly greater than 50 percent.”

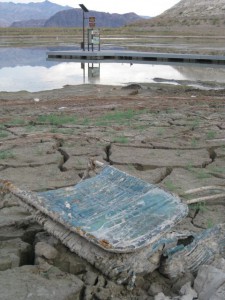

- 2013-14 water year: With 750,000 acre feet less of water flowing in, a Mid-Elevation Release Tier declaration means Lake Mead would then end the 2014 water year with a surface elevation of 1,081 feet above sea level, according to the Bureau’s latest numbers, more than 8 feet lower than if there is a full release from Powell. That would be the lowest Mead’s been at the end of a water year since 1936 (data here), setting the stage for the first ever shortage declaration the following year.

- 2014-15 water year: With Powell forecast to stay low, a second Mid-Elevation Release Tier year would likely follow, leaving Lake Mead 10 feet lower by the summer of 2015. In August 2015, a similar projection to the one described above will be done for Lake Mead. If it shows Mead below 1,075 feet above sea level the following year, a formal shortage will be declared and deliveries to Arizona and Nevada will be reduced incrementally to save water. (I’m a little confused about whether the reduced deliveries would kick in at the start of the water year – Oct. 1, 2015 – or on the following Jan. 1. If you’re steeped in the Law of the River and know the answer, leave a comment or email me at jfleck@inkstain.net.)

I apologize for the complexity. If I can find a simpler explanation, I’ll get back to you, or maybe write a book.

Pingback: Will the #ColoradoRiver 2007 Shortage Sharing Agreement for the come into play this season? | Coyote Gulch

Pingback: Shortage on the Colorado River : jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Going to LA | Frederick Guy

Pingback: ‘There’s no reason to run around like your hair’s on fire’ — John Fleck #ColoradoRiver | Coyote Gulch