update, June 24, 2015: Since this post was written in April 2015, a wet spring has reduced the chance of a “shortage” in 2016. It now appears 2017 is the earliest this could happen. The situation described in rest of the post, detailing what happens when a “shortage” is declared, remains the same.

previously

tl;dr There is a clear possibility of a shortage declaration on Lake Mead in August, which would force a reduction in Lower Colorado River water deliveries, primarily to Arizona, in 2016. Nevada and Mexico would also see small shortages. Neither California, nor the states of the Upper Basin (New Mexico, Utah, Colorado and Wyoming) will see any curtailments.

This is a big deal, but it is almost entirely an Arizona big deal. Arizona currently has the slack in its system to absorb the reductions, including possibly deeper cuts if Mead continues to drop, without major disruptions. The Phoenix and Tucson metro areas are not going to dry up and blow away.

Longer details below:

Built in the 1930s in a canyon on the Arizona-Nevada border, Hoover Dam impounds Colorado River water in Lake Mead. It protects valleys along the lower river from flooding, and stores water during wet years for use during dry years in Nevada, Arizona, California, in the United States, and Baja and Sonora in Mexico. From the beginning, California has taken its share of water through an aqueduct that carries water to Los Angeles, and a second that carries farm water to the Imperial Valley. A significant share of the river’s water also supplies farms and communities in Arizona along the river itself, from Parker south to Yuma. But for the first three-plus decades of the dam’s existence, Arizona had no way to get the river’s water to its major population centers in the state’s central desert valleys.

In 1968, in return for political support from California to win federal funding for the Central Arizona Project, Arizona cut a deal: California would not block the project, which would use federal money to build a canal to carry 1.6 million acre feet of water per year up from the Colorado River and into Phoenix and Tucson. In return, Arizona would agree to subordinate its priority for the 1.6 maf water to California’s. (This Reg Manning Arizona Republic cartoon suggests some hard feelings about all this.)

That means that if the river is short, essentially all the cuts come to Arizona’s share of the Colorado River’s water. This is important point number one:

- It takes many more years of shortage before California loses a drop.

Southern California – mostly farmers in the Imperial Valley but also urban/suburban LA and San Diego, won’t lose any water. They’ve got enough to worry about right now with their own drought. Drought in the Colorado River Basin won’t add to their problems.

Important point number two:

- Arizona’s major on-river agricultural water users, primarily the Colorado River Indian Tribes and the farmers of the Yuma area, also would not lose a drop under a shortage. Their rights are older, and not crimped by the 1968 California bargain.

But what does “shortage” actually mean, and who gets to decide when the river has a shortage and deliveries are to be curtailed?

The legal authority rests with U.S. Interior Secretary Sally Jewell, but back in 2005-07 the federal government and states decided the rules for making the decision were too squishy, so they came up with a really crisp definition: when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s August version of its monthly planning document known as the “24-month study” shows that Lake Mead is expected to drop below a surface elevation of 1,075 feet above sea level, a shortage shall be declared.

This is important point number three:

- Don’t freak about about those “Lake Mead drops below 1,075” headlines. Just because Lake Mead drops below 1,075, which it’s likely to do next month, does not mean a shortage declaration then and there.

We’ve all got to wait for the August 24-month study. (You can find the 24-month studies here. If you want to nerd out on Colorado River system numbers, they’re the place to start. A huge hat tip to Dan Bunk and his team at the Bureau’s Boulder City, Nev., River Operations Group that does the hard work of producing them.) In February, the Bureau’s staff concluded there was a 21 percent chance of a shortage kicking in Jan. 1, 2016, and a 54 percent chance in 2017. But that was before this incredibly epically crappy hot dry spring. I’m told that the new 24-month study, out later this week, will be dancing perilously close to the 1,075 number for its Jan. 1 projection. But still, don’t freak out. Wait until August!

So what happens in Arizona if there is a shortage?

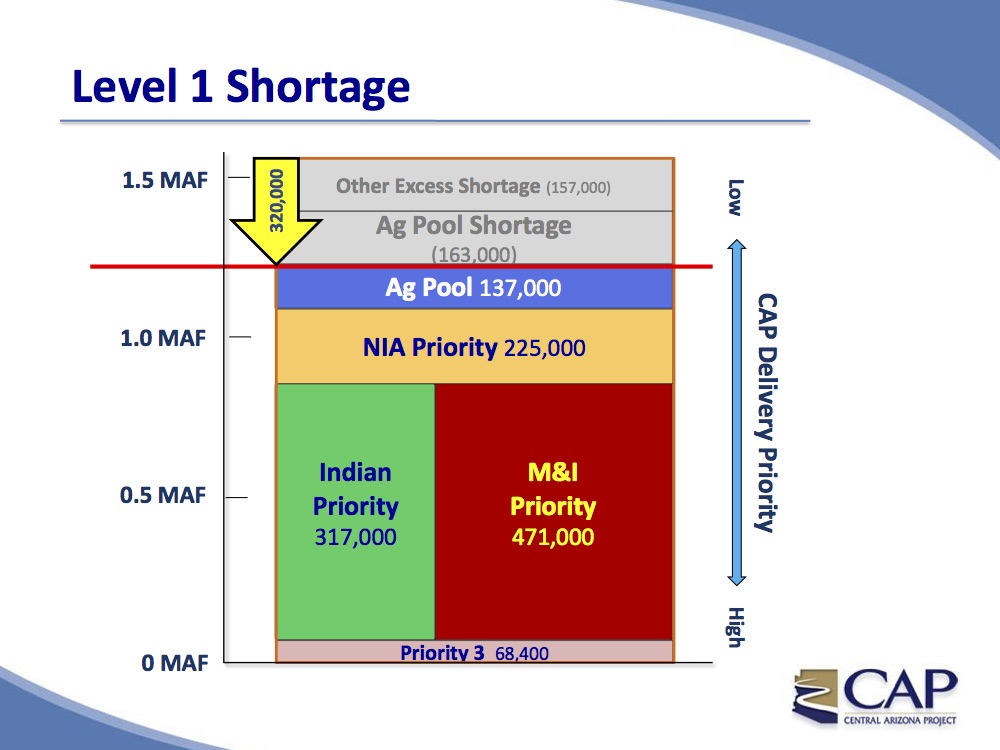

Arizona loses 320,000 acre feet of its 1.6 million acre foot Central Arizona Project allotment, or about 11 percent of its total Colorado River allotment. (Nevada loses 13,000 acre feet, and Mexico will get shorted 50,000 acre feet.)

So who in Arizona gets shorted? The Central Arizona Project allocations were built with the idea that a shortage was a real possibility, so the current priority structure for distribution of water includes both high and low priority uses, as defined by Arizonans themselves. Lower priority uses, included “excess” category for things like groundwater storage for later use and low-priority agriculture would get shorted. A lot of ag water would not, and Indian and city water (Phoenix, Tucson – “M&I” in the chart below) will see no shortage.

Here’s CAP’s explanation of the process:

CAP would manage a shortage by first reducing the excess water deliveries and ceasing portions of its recharge operations. Second, CAP would limit its water delivery to agricultural customers, who have limited rights to CAP water and could turn to pumping groundwater or other sources. If reductions are required beyond this level, then CAP would begin to recover CAP water stored underground. This would be done to protect existing municipal and industrial CAP customers from experiencing reductions in deliveries of CAP water and to recover water stored to meet Arizona’s obligations pursuant to Indian Water Rights Settlements.

“Shortage” here is an orderly process by which Arizona has formulated a plan to conserve water when there’s not enough to go around.

It’s worth comparing this to what is happening in California’s Central Valley. On the Colorado, under the first shortage, Arizona takes an 11 percent hit while everyone else is essentially kept whole. We’re now 15 years into a drought deeper than any contemplated when the Lower Colorado River water delivery system was built, and everyone up to now has gotten a full supply. That’s a pretty robust system. Compare that to California’s Central Valley Project, where “shortages” happen frequently. This year, initial agricultural allocations are zero, and M&I allocations are 25 percent (pdf).

update: A friend wise in the details of the Colorado River, who also happens to live in its Upper Basin, notes that none of this applies in the Upper Basin states of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. Shortage is an entirely different phenomenon, driven by the availability, year to year, of headwaters streamflow. Important point number four: When it’s dry, shortage happens there, and junior users are curtailed, routinely.

Wonderfully explained. Have we reached the point where folks who, like me, haven’t paid enough attention, but, unlike me, have tons of money to invest, will now understand, pay attention and start pulling out of investment in these areas based on this? Even if their industry isn’t directly tied to water?

Thanks for the great summary. A declaration of shortage will have reverberations throughout the basin even if it doesn’t directly affect CA and the upper basin states.

Scot – I’ve been trying to think of what the market opportunities are here. If you’re right, smart investors have already sussed this out, and there must be some commodity or index traded fund or something that is moving based on this sort of thing. What would it be?

Pingback: Lake Powell takes a big hit in latest Bureau forecast | jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: The Upper Basin: the Colorado River shortage that has already happened | jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Lake Powell spring runoff forecast this year now less than half of average | jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: In a Colorado River shortage, Central Arizona will be fine for now | jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: 1080.18: Lake Mead breaks another record, lowest since it was filled | jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Risk of Colorado River shortage declaration rising | jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Colorado: Annual State of the River sessions include vital information on snowpack, stream flows and reservoir operations | Summit County Citizens Voice

You should be more worked up this could seriously affect the enviroment. [ignore the bad spelling]

I hate this article you don’t even care about the enviroment do you

Pingback: Lower Colorado shortage now unlikely in 2016, maybe not in 2017 | jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: The Lower Colorado: no shortage for now, but that pesky structural deficit's still there - jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Blog round-up: Eminent domain and the BDCP, Troglodytes defend the Governor’s tunnels, Optimism and the hazards of technology; Why groundwater regulation fails; and more …MAVEN'S NOTEBOOK | MAVEN'S NOTEBOOK

Pingback: One in five chance of Colorado River shortage in 2017, 50-50 by 2018 - jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Grass lawns becoming less common around metro Phoenix - Arizona (AZ) - Page 7 - City-Data Forum

Pingback: Odds now favor a Lower Colorado River Basin shortage declaration in 2018 - jfleck at inkstain