By Eric Kuhn

This winter’s decent snowfall has turned into an abysmal runoff on the Colorado River, thanks to the dry soils heading into the winter, along with a warm spring. It’s alarming, but given the large amount of storage capacity in the basin and the recent string of good runoff years in the upper Basin, with five of the last six years close to average or better, most of the basin’s water users will not face significant problems this year. Our bigger concern is what happens next year. Are we headed for a multi-year drought?

Watching the bottom drop out

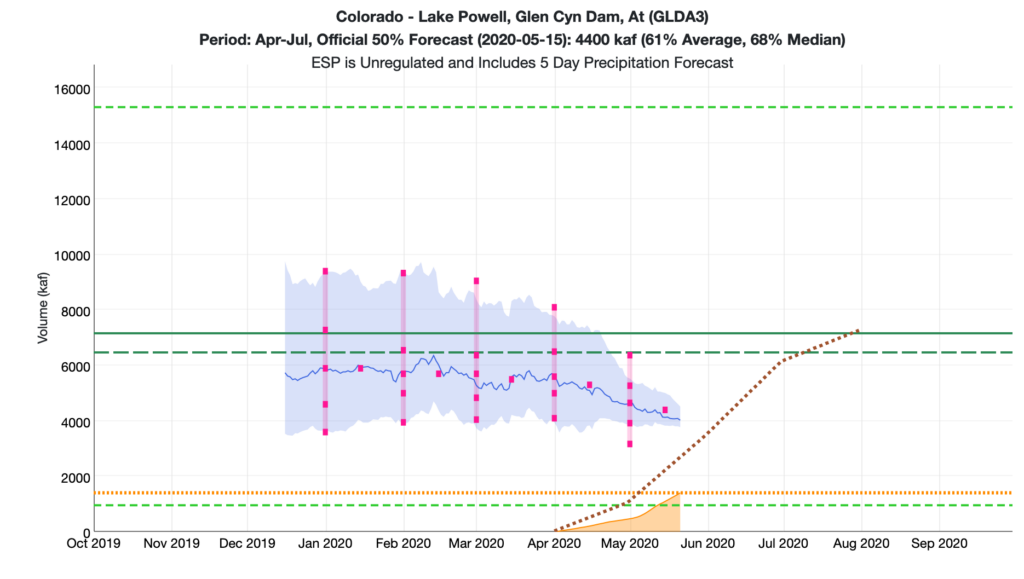

As of the third week of May, the Colorado Basin River Forecast’s Center’s (CBRFC) daily model is closely tracking the minimum probable forecast inflow to Lake Powell used by the Bureau of Reclamation to prepare its April 2020 24-month study. The 24-month studies are an important decision-making tool under the 2007 Interim Guidelines, which govern the river’s operation. The 24-month studies show projected monthly reservoir inflows, storage elevations, water deliveries, power generation, and other system data for the next two years. They support critical operational decisions under the Interim Guidelines and associated drought contingency plans, including annual releases from Glen Canyon Dam and shortage levels for Lake Mead water contractors.

Reclamation’s monthly 24-month studies for January – July are based on the CBRFC’s most probable unregulated April-July inflow forecast for Lake Powell and other key Upper Basin reservoirs. Approximately quarterly Reclamation also publishes 24-month studies based on high flow and low flow scenarios for the remainder of the runoff year – a one-in-ten chance “worst case” and a one-in-ten chance “best case.” This April’s 24 month studies were based on a most probable April – July inflow to Lake Powell of 5.6 million acre-feet, a minimum probable inflow of 4.1 million acre-feet, and a maximum probable inflow of 8.1 million acre-feet. The CBRFC daily model runs now show about 4 million acre-feet, worse than the April minimum probable forecast. For Water Year 2020 (all 12 months not just April- July), the total unregulated inflow to Powell is projected to be 6.7 million acre-feet, about 60% of average, a little more than half of WY 2019’s 13 million acre-feet, but better than the 2018 drought year of which had an unregulated inflow of 5.5 million acre-feet.

Little impact this year, the potential for big impacts in the future

What does this dry 2020 year mean for the operation of the Colorado River basin, specifically, Lakes Powell and Mead? Based on the 24-month studies, the answer is not much. The 2020 operations are already fixed. Glen Canyon Dam will release 8.23 million acre-feet and Lake Mead users will be in a “Tier Zero” shortage under the DCP, requiring a small amount of conservation. Even before the official “Tier Zero” declaration, Lower Basin users were voluntarily saving more than the cuts required under the DCP. And, even if this year’s runoff continues to decline, it is very unlikely to change next year’s projected annual release of 9.0 million acre-feet from Glen Canyon Dam. Based on the April minimum forecast, at the end of calendar year 2020 Lake Powell is projected to be about 20’ higher than the 3575’ elevation trigger that would result in a reduction of Glen canyon releases to 7.48 million acre-feet in WY 2021. 20’ of elevation in lake Powell at current levels is almost two million acre-feet of storage. It’s very unlikely that the forecast will lose or be off by that much water.

This good news is the result of last year’s big winter which gave us an above average runoff, charging Lake Powell and the other Upper Basin Reservoirs. The real concern for the basin is not 2020, but 2021 and beyond – will 2020 be the first year of a multi-year drought period? The last significant multi-year drought in the Colorado River basin was 2012-2013. The second year of a multi-year drought tends to have greater impacts than the first, as water managers try to refill upstream reservoirs, amplifying the multi-year drought impacts on Lake Powell. If 2021 is again dry (below about 70% of average), the storage elevation of Lake Powell could easily drop below elevation 3575’ reducing the annual Glen Canyon Dam release in WY 2022 to 7.48 million acre-feet, pushing Lake Mead into a Tier One shortage. A three-year drought or longer would quickly push Lake Mead downward requiring the large shortages anticipated by the Interim Guidelines and Lower Basin DCP.

Multi-year droughts

Looking at the Bureau of Reclamation’s natural flow data base (NFDB, Jan 2020 version, 1906-2018), two-year droughts are relatively common, three years and longer, less so. The driest two through four-year periods are shown below:

| Two-year periods | average annual flow |

| 2002-03 | 8.163 MAF/year |

| 1976-77 | 8.318 MAF/year |

| 2001-02 | 8.447 MAF/year |

| 2012-13 | 8.708 MAF/year |

| Three-year periods | |

| 2002-04 | 8.589 MAF/year |

| 2001-03 | 9.116 MAF/year |

| 2000-02 | 9.145 MAF/year |

| 1954-56 | 9.878 MAF/year |

| Four-year periods | |

| 2001-04 | 9.198 MAF/year |

| 2000-03 | 9.472 MAF/year |

| 1953-56 | 10.197 MAF/year |

| 1989-92 | 10.487 MAF/year |

As one can see, many of the driest multi-year periods are associated with the 2000-2004 drought period, which is by far the driest five-year period. What should concern us is the threat of anthropogenic aridification making multi-year droughts more common. Three of the four driest two-year and three-year periods as well as the driest four and five-year periods have all happened in the last 20 years, which, not coincidentally happens to include almost all of the warmest years the basin ever recorded in the basin.

Implications for future river management

Being better prepared for future multi-year droughts will be one of the challenges facing the basin stakeholders as they begin to consider the post-2026 river. For example, even though Water Year 2020 has turned surprisingly dry and the basin is under an escalating threat of multi-year droughts, the only parameters used to determine the annual release from Glen Canyon Dam are the projected elevations of Lake Mead and Powell from the 24-month studies. Therefore, the annual release from Glen Canyon Dam for Water Year 2021 will be 9.0 million acre-feet, 750,000 acre-feet more than the normal minimum requirement, putting the Upper Basin under additional risk if next year and beyond are dry. Parameters such as recent trends of naturalized stream flows and regional temperatures, longer-term forecasts, and the consensus messages from climate science are not currently considered.

For the river’s post-2026 operational guidelines, let’s hope that changes.