A small flowing river to the right, a dry arroyo to the left, a railroad bridge crossing the dry arroyo, a mountain in the distance, a bicycle laying in the sand in the foreground.

SAN ACACIA – It’s three river miles upstream from the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District’s San Acacia Diversion Dam to the Rio Grande’s confluence with the Rio Salado, but the river’s twisty here. It wasn’t much more than two miles of bike ride along the MRGCD’s Unit 7 Drain service road to get to the railroad bridge over the Salado. Although not a bike ride the whole way. Super sandy. Lots of walk-a-bike.

From the Salado, it’s another eight miles (again river miles, but less twisty) to the Rio Puerco.

The sand is typical of the Salado’s coarse-grained sediment load. The Puerco tends to be more silts and clays. Together, they remind us that rivers bring with them more than water.

On August 13, 1929, both the Puerco and the Salado were flashing together. The flow on the Salado that day was later estimated at 27,000 cubic feet per second. The Puerco’s flow was estimated at 31,000 cubic feet per second. The Rio Grande today when I rode out there was maybe ~250 cfs, based on the gage upstream at Bernardo. The Salado, as you can see, was 0 cfs, which is what it almost always is. Until it isn’t.

The flood of August 13, 1929, seems to have destroyed the community of San Acacia (that’s what the breathless newspaper accounts of the day all said, Further Research Needed). Among the losses was the home of Philip Zimmer, patriarch of a storied San Acacia family. Here’s the Associated Press:

One of the tragedies of the floods was the destruction of the famous Zimmer library of antique Spanish books which Mr. Zimmer had found years ago on Indian hill. The library was estimated to be worth $50,000 and it could not be replaced. The priceless volumes were ruined by the flood waters.

The Zimmer estate was one of the finest in this section of the Rio Grande valley and had one of the largest orchards in the valley.

The story of the 1929 destruction of San Marcial, 47 river miles downstream, gets most of the storytelling love, but I’m interested in San Acacia. Geomorphology is always destiny for river communities, and in this regard San Acacia is in no way unique. But it’s presence at the mouth of a narrow canyon, just downstream from two big, silty Rio Grande tributaries, is a great story I’d like to figure out how to tell.

It’s a narrow gap between two volcanic bluffs, maybe 600 feet wide at its narrows. Through this gap flows the railroad (Can I skip all the mergers and acquisitions and just call it “the Santa Fe”?); the MRGCD’s Unit 7 Drain; the river’s main channel.

The MRGCD’s San Acacia Diversion Dam forms a low 660-foot plug across the gap, and the piles of dirt attest to the contributions of the Puerco and the Salado. Back in September 2013 I saw the river at 9,000 cfs here, the biggest flows since 1985, the Puerco and Salado both dumping flash flood waters into a roiling muddy power that is part of what draws me back again and again. I can’t fathom 31k cfs from the Puerco and another 27k from the Salado.

Downstream of the gap, you’ve got the Santa Fe, the Rio Grande’s main channel, and the headings for the Socorro Main Canal and the Low Flow Conveyance Channel. Splitting off the Socorro Main is the Alamillo ditch (which provided a convenient escape route on today’s ride from a very fit and hard-working dog displeased with my presence).

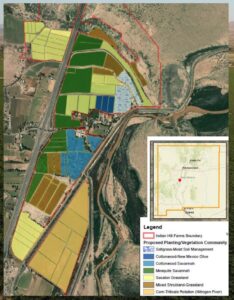

The Alamillo heads due west away from the river, across a gorgeous fan of Salado and Puerco sediment, green with alfalfa as I rode along the ditchbank today. The land, known as Indian Hill Farms, was until recently owned by the late Corky Herkenhoff, one of Philip Zimmer’s descendants.

KRQE had a story about Pattern Energy, the company building the big SunZia renewable energy power line, buying Indian Hill Farms with plans to convert it into habitat as mitigation for power line construction. At a Sandia Labs presentation last fall, Pattern’s Jeremy Turner shared preliminary plans for the conversion of Indian Hill Farms to saltgrass and cottonwoods and savannah.

Before his death, I spent time with Corky piecing together some of the history of Indian Hill Farms, originally planning a chapter for Ribbons of Green, the book Bob Berrens and I were writing about the Rio Grande and the making of Albuquerque. It was fascinating stuff, but it fell out of the narrative as our geographic scope shrank between envisioning the book and actually putting words to paper.

As I play with ideas for the next book, I’ve got a long string on my hard drive about the floods of September 2013, a text from Corky telling me he’d driven up to check on the Salado and that it was flashing, hard. We knew the Puerco was flashing as well, it’s got a gage, but Corky had to drive up to look to see what the Salado was doing.

The thread on my hard drive includes data from the USGS about the volume of sediment that blasted into the Rio Grande’s main channel that September day – A LOT – and visceral feel of watching that thick soupy sludge roaring over the San Acacia Diversion Dam, the way I kept running into other water nerds down there that day. We all had to see it.

Corky, who grew up hanging out summers at his grandma’s San Acacia farm before taking over the operation as a young man in the 1960s, told me one time that the Salado and the Puerco had distinctive smells when they were flashing, that he could tell the difference. I asked a couple of Conservancy District guys at the San Acacia Dam, just down the road from Corky’s farm, if they could tell the difference by the smell. They said “no.” I told them they Corky told me he could tell the difference. They smiled and nodded. They believed Corky could.

There was a tenderness in the way Corky pronounced “Salado” that always charmed me – “suh-*low*”, almost rhyming with “cow” but with a barest shadow of the “d” somehow tucked into the middle of the second syllable. It suggested an intimacy with the river, with the place. Not a lot of people love the Salado, or even know that it exists.

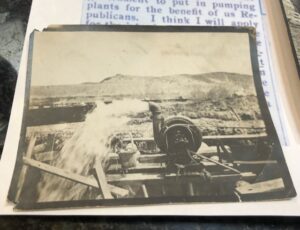

On one of my last visits, Corky had a bunch of old pictures to show me, including this one, of his great-grandfather Philip Zimmer’s first groundwater well, circa 1904. Looking this evening at the New Mexico Office of State Engineer’s water rights maps, I see a permitted irrigation well on the northeast corner of Indian Hill Farms. I don’t understand its lineage, I have no idea if there is a legal water rights tendril extended back to Zimmer’s 1904 well. Further Research Needed. But there is a tendril nevertheless, a storytelling thread worth tugging.

What matters more for that thread is the current owner: Sunzia Transmission, Llc, 1088 Sansome St., San Francisco, CA, 94111.

Glad that you are reporting on Corky. He was a great framer and inspired me to get involved with water issues. RIP Corky.

Nice!

It’s wild to think about the Salado and Puerco with five-digit flows. Or four-digit flows, for that matter.