The Rio Puerco, just upstream from its confluence with the Rio Grande. Sept. 19, 2025, by John Fleck

Deepening and widening of stream channels in the Southwest is a phenomenon that has taken place within the memory of men now living. It began at different dates from 1860 on and has progressed at different rates on several streams, as summarized in a recent paper.²? The flood plains of numerous minor streams are yet undissected, but nearly every one of them is menaced by a deep channel, or arroyo, which visibly increases headward each year. These channels, or arroyos, not only grow headward through the smooth flood plains of the valleys but constantly widen by lateral cutting and the growth of minor tributaries. It seems inevitable that the present flood plains will eventually disappear and new flood plains will form at lower levels.

- Bryan, Kirk. “Channel erosion of the Rio Salado, Socorro County, New Mexico.” US Geological Survey Bulletin 790 (1927): 17-19.

The Rio Puerco, a tributary of the Rio Grande in New Mexico, has deepened and widened its channel, or arroyo, since the settlement of the region. This process of accelerated erosion still continues. Historical evidence, largely the notes and maps of government land surveyors, is cited to show that the cutting began between 1885 and 1890. The deepening of the arroyos has decreased the agricultural and grazing value of the country, resulting in the abandonment of six small towns and numerous ranches. The coincidence between the introduction of large numbers of stock and the cutting of arroyos indicates that overgrazing precipitated this form of destructive erosion. The ultimate cause, not completely discussed in this paper, appears to lie in cyclic fluctuations in climate.

- Bryan, Kirk. “Historic evidence on changes in the channel of Rio Puerco, a tributary of the Rio Grande in New Mexico.” The Journal of Geology 36, no. 3 (1928): 265-282.

Kirk Bryan, a child of Albuquerque, was still in his 20s when he was tromping around the Rio Puerco and Rio Salado, gathering data to inform the plans for the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District and trying to make sense of the messy reality of these two fascinating tributaries to the Rio Grande. He bore the label “geologist” before the branch of the science now labeled “geomorphology” had grown strong enough to stand on, and in the decades that followed this work he did much to establish the foundations for our understanding of arid landscape rivers.

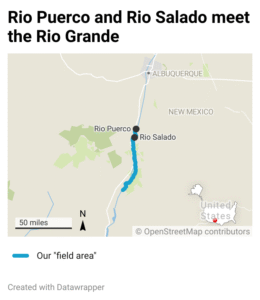

In choosing this stretch of the Rio Grande to write about for the next project – from the confluence of the Rio Puerco downstream to to Elephant Butte Reservoir, what I’ve taken to calling our “field area”- we’ve granted ourselves permission to reach upstream on the Puerco and Salado, and also upstream into our evolving understanding of the geomorphology of these two remarkable streams.

Joseph Burkholder, the chief engineer for the nascent Conservancy District, dispatched Kirk Bryan and George M. Post (whodat?) to sort out the challenges posed by the Puerco as it dumped its massive sediment load into the main stem of the Rio Grande downstream of Belen, New Mexico. From Burkholder’s report:

The Rio Puerco is the largest producer of silt, being the tributary having the largest drainage area and being subject to frequent silt-laden floods. In the report by Kirk Bryan and George M. Post on the “Erosion and Control of Silt on the Rio Puerco, New Mexico”, it is stated that nearly 400,000 acre feet of valley soil has been carried away by the erosion of streams and arroyos in the Rio Puerco valley during the last 40 to 50 years. It is also estimated that some 9,000 acre feet of silt is brought to the Rio Grande annually from the Rio Puerco, which is therefore held responsible for almost one half of the 20,000 acre feet of silt which is annually deposited in the Elephant Butte Reservoir.

The sediment is a central feature of the new project – river management as sediment management.

One of the things that interests me as I work my way through Bryan’s early work is the very human way he is doing his science, describing the relationship between people and their rivers: “decreased the agricultural and grazing value of the country”; “abandonment of six small towns and numerous ranches”; “most of the agricultural land in the valley has been destroyed.” A century of research since he published in the 1920s has only enriched our understanding of the interplay between climate and human impacts on the landscape. His basic thesis about the Puerco in the 1928 paper – yeah, grazing for sure, but also climate – has grown richer in its nuances and details, but the basic tension between those two causal threads seems to remain.

Trying to reach the confluence

I’ve been trying to carve Fridays out of my calendar for “field work.” It’s an hour’s drive to the field area. With a couple hours riding around on my bike looking at stuff (field work!), I can be back in time for lunch and an afternoon to write.

We’ve had a nice blast of late summer rains over the last couple of weeks, and the Puerco has been running (it mostly doesn’t), so I threw a bike in the car this morning and drove down to take a look. Down a decent dirt road, atop what passes for a levee, I was greeted by a riot of blooming chamisa doing their “it rained, let’s get on it” routine. The cloud deck hung on through the morning hours, perfect riding weather, and the rains had packed down the road enough that it was easy going – only a few sandy patches.

The Puerco had been been up over 100 cfs for the last few days, but was down to 20-ish this morning when I finally had a chance to go see the muddy mess for myself. 100 cfs is the highest flow this year, but that’s a trickle compared to the recorded peak flow of 18,800 cfs in September 1941. I saw it in September 2013 at maybe 9,000 cfs (not sure exactly, it had blown out the gage).

I tried again to get to the confluence (I’d tried last month and was thwarted by sketchy no trespassing signs), this time from the north on land that seemed less likely to be legally encumbered. I’d talked to some elk hunters on one of my last field expeditions who suggested it was doable. After three miles the road fizzled into some skanky double-track, then shrank to path, which someone (hunters? I saw a few shotgun shells here and there.) had kindly cut through an otherwise impenetrable thicket of bosque, but the path petered out into the river bed of the Puerco itself about a hundred yards short of the actual confluence. It was such a gloppy muddy mess I decided against pushing on.

I’ll be back when it’s dry.