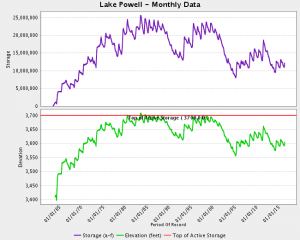

The trick now is for the three U.S. states sharing the Colorado River’s water downstream of of Lake Mead – Nevada, Arizona, and California – to negotiate some sort of a deal that reduces their collective take on the river. That’s trick one. Trick two is for state negotiators to then sell the deal back home to sometimes recalcitrant local water agencies that take a dim view of giving up water.

As, for example, San Diego?

First, the case for a deal:

Under current law, California has first dibs on much of the river’s water. California’s rights to the Colorado are so secure that the Central Arizona Project —a 336-mile series of canals and pipelines that brings river water to 80 percent of Arizona’s population— would have to run dry before California has to lose a single drop.

That is the consequence of a deal worked out in the late-1960s. That might be the law, but it’s now hard to imagine letting civilization in Arizona wither while California is unscathed.

Water officials involved in the negotiations worry that without a new deal, politicians will eventually decide everyone’s collective fates rather than technocrats like themselves with experience managing water.

That’s Ry Rivard getting to the heart of why California looks like it may be willing to make a deal on the Colorado that gives up water to which the state might feel legally entitled. But then:

The San Diego County Water Authority is not involved in the negotiations. Instead, it’s on the sidelines and taking a dim view of the talks. The Water Authority calls them a “dubious closed door process.”

This is one of the key arguments I make in my book (pre-order now!) – the importance of the interface between large scale basin-facing management processes and all the local agencies back home that actually distribute the water. Our success or failure at that interface is precisely our success or failure at keeping the system from crashing.