Palo Verde Irrigation District alfalfa, Blythe Calif., February 2015, photo copyright John Fleck

One of California’s largest Colorado River farm water districts is suing the state’s largest municipal water agency, charging that efforts to move farm water to cities are threatening the viability of agriculture in one of the oldest farming valleys on the river.

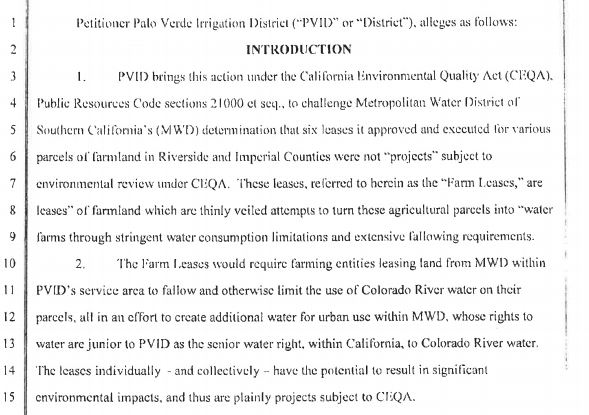

The Palo Verde Irrigation District, in a suit filed last month in Riverside County Superior Court, is charging the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California with “thinly veiled attempts” to turn agricultural land it owns in the Blythe Valley into “water farms” by placing water consumption limits and fallowing requirements on the land in order that water from the parcels could be moved to use in Southern California’s coastal cities.

Sorry, I only have a scan of a fax, but here’s PVID’s opening gambit:

PVID v. MWD

(For those interested in following along at home, it’s Case No. RIC1714672 in Riverside County Superior Court.)

Met and PVID have a long and cordial relationship, with one of the pioneering ag-urban transfer agreements that compensates farmers for fallowing land in dry years to move water to cities. But the relationship has been complicated in recent years by Met’s decision to buy up some 22,000 acres of land in the district. The lawsuit is a first salvo in what’s shaping up as a conflict over whether, if water use is reduced on the land Met owns, that saved water can be then shipped via the Colorado River Aqueduct to coastal Southern California cities.

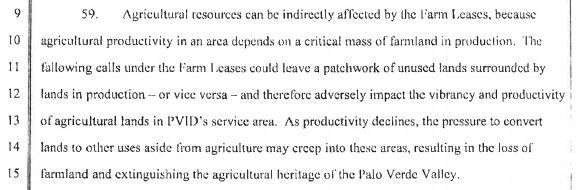

In its suit, PVID argues that there’s what we economics faculty would call “an externality” that must be considered under California’s environmental review statutes:

PVID v. MWD

To be clear, Met has repeatedly insisted that it is not going to dry up the Palo Verde Valley. As Tony Perry put it in the LA Times two years ago:

Their message: No harm will come to the agricultural economy of the Palo Verde Valley. MWD plans to abide by the 2005 agreement, which caps at 35% (26,000 acres) the amount of the valley’s farmland being fallowed. More than 25,000 acres are fallowed currently.

Randy Record, the MWD board chairman, said he wants to reassure farmers and others in Palo Verde that the local economy will not be hurt.

“I’m a farmer myself,” Record said. “For me, the [fallowing] program is not a success unless it benefits both parties.”

But for what it’s worth, now they’re all in court.

This implicates deep questions in these ag-urban water transfers – should preserving agricultural communities be a policy goal, and if so how to achieve it?

This is a conflict that will be closely watched across the West, because if rather than negotiating complex water transfer deals with ag agencies cities can simply buy up farm land and take the water, the policy landscape (and the underlying real landscape, shaped by those policies) becomes a very different thing.