The sun is shining, the grass is green

The orange and palm trees sway

There’s never been such a day

In Beverly Hills, LA

But it’s December the 24th

And I’m longing to be up north– Irving Berlin

The backyard of my childhood home, in the foothills above Upland, California, was a remnant of an old orange grove. It still had a concrete irrigation standpipe (I think that’s what they’re called?) like the one in the picture. No water came out – such are the traces of Southern California’s agricultural past as we brought water to the land, grew food, then moved on.

There were still groves checkerboarded through our neighborhood in the 1960s when I grew up, a past I romanticize – the smell when the trees were in blossom, the sound of wind machines on the rare cold mornings, the way my parents’ bridge game with their friends Dick and Elizabeth Fleming would stop so Dick could listen turn up the radio to listen to the fruit frost report.

I had a longstanding tradition when I worked for the Albuquerque Journal of writing a White Christmas story, generally about how it was not going to be one in Albuquerque that year. I learned early the benefit of exploiting editors’ needs to fill the paper on slow news days to write the oddball stuff, the week before Christmas is invariably slow, and so I got away with a great deal in my annual riff about why it was, yet again, not likely to be a White Christmas.

I was goofing, but I took the work seriously:

It’s perhaps worth remembering the first verse of Berlin’s White Christmas — the “lost verse” that is often left out in our recreations of hearth and home.

In it, the song’s narrator is stuck “in Beverly Hills LA,” where “the orange and palm trees sway” — stuck in a place with no snow, and “longing to be up north.”

New Mexico is on a climate/cultural border between the snowless “Beverly Hills LA” and the Connecticut farm in the 1942 movie “Holiday Inn,” starring Bing Crosby, which introduced Berlin’s dreamy cinematic vision of snow at Christmastime. Unless you live in the high country, a white Christmas is better imagined than experienced.

Nathan Masters wrote earlier this month on the loss of snow in Los Angeles:

For generations, Angelenos could count on waking up, at least once or twice in their lives, to a wintry scene: children pelting each other with snowballs beneath powder-dusted palm trees.

For me, it was the Friday before Christmas, 1969:

I was in fifth grade, and it was the Friday before Christmas, and my teacher wouldn’t let me go out and play with the other kids because I had a little bit of a cold.

I do not remember the teacher’s name, but I have not forgiven her.

Old Baldy Brand oranges

If you look in the foothills in this citrus crate label, just to the left of the flag pole, that’s where our house was. The Chaffey Brothers, William and George, developed the irrigation colony that became Ontario and Upland.

So there are two threads here, and they are in conflict. In White Christmas, one of the great set pieces of Americana, Irving Berlin sets the real America apart from the orange and palm trees, the artificiality of “Beverly Hills, LA”.

The citrus crate labels I so love are precisely that, an artificial marketing dreamland created to sell Southern California fruit back east. It worked. There was a time, they say, when Riverside County was the richest place per capita in America.

But that gauzy citrus landscape is also the America of my childhood.

So was Irving Berlin’s White Christmas, artificial but with the power of a narrative that was self-executing. Here’s music critic Jay Rosen, from his wonderful book White Christmas: The Story of an American Song:

The longing for Christmas snowfall, now keenly felt everywhere from New Hampshire to New Guinea, seems to have originated with Berlin’s song.

I love the orange crate labels (check out the University of California library collection) in the same way that I love Bing Crosby singing White Christmas. Like the orange crate label artists, Berlin made up a world that, in our own longings, then became real.

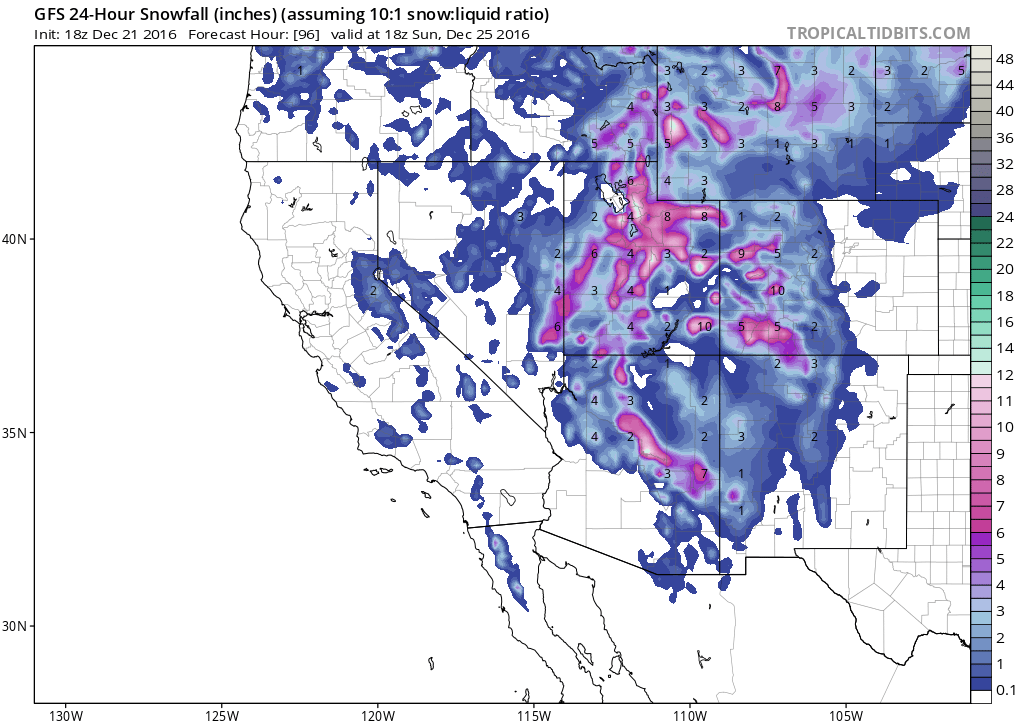

So with that, via NCEP’s Global Forecast System Model, here’s your White Christmas forecast for total snowfall for the 24 hours ending midday Sunday:

sleigh bells in the snow