ESTANCIA – It occurred to me yesterday why I’m so fascinated by the pinto bean farmers of the Estancia Basin. They are very much like the trees prized by the scientists who use tree rings to piece together ancient climates: at the edge of their range, and therefore sensitive to small changes in climate that a fatter and happier tree might take in stride.

Lissa and I were on a wander Sunday through the basin, which runs down the east side of New Mexico’s central mountain chain, an hour east-southeast of Albuquerque. I’m fascinated by the place because it’s a perfect lab for the sort of climate storytelling I’m interested in. In the late Pleistocene, during the tail end of the last ice age, the enclosed basin held a lake that rose and fell with the changing climate. By some 10,000 years ago, the lake was gone, save for one brief resurgence. In more modern times, the Tompiro lived in the region, in cities like Gran Quivira, on a hill at the far southern edge of Torrance County. They traded the salt that can still be found in the playas in the bottom of old Lake Estancia. It is those same playas, dug by the wind, that gave scientists their first glimpses of the layering of the lake’s sediment that makes ancient Lake Estancia one of interior North America’s great paleoclimate tales.

Gran Quivira offers one of the southwest’s spectacular tales of drought-triggered collapse, made interesting by the social and political complexities of the arrival of the Spanish half a century before the Tompiro abandoned the region for good.

But it’s the pinto bean farmers who have captured my interest of late. The basin’s a tough place to live, and it was only homesteaded after the good land to the east was gone. It’s marginal stuff for dryland farming – Estancia, in the basin’s center, averages a bit less than 13 inches (33 cm) of precipitation a year. Remember that John Wesley Powell, in the 19th century, called 20 inches (51 cm) the dividing line for rain-fed agriculture. Beyond that – beyond the 100th meridian that roughly followed the 20-inch contour line – agriculture without irrigation was a risky endeavor in many years, Powell opined. But who listened? For a time, in the early 20th century, the folks who lived there liked to call the Estancia Basin “The Pinto Bean Capital of the World.” In 1938, the local high schools – Encino, Cedarvale, Corona, Willard, Mountainair, Moriarty, Estancia – banded together to form the “Bean Valley Conference,” kids competing in basketball, football, baseball and track.

In the old ag census data, you can see bean farming fall off the table in the late 1940s, as the early stages of what we’ve come to call “the drought of the ’50s” was setting in. I’m still sorting through census data, so there may be some complications to the story that I’m not getting yet, but it appears clear that the Estancia Valley is a repeat of the familiar southwestern story, the same thing that happened when the Spanish happened upon the Tompiro at Gran Quivira three centuries before: expand during stable, wet times, get hammered when drought returns. There’s not much margin in agriculture at 13 inches per year, not much slack to be taken up in the dry years.

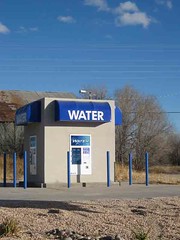

Today, you can still see center pivot irrigation systems up and down NM 41, the main north-south highway through the Estancia Basin. The spring around which the community of Estancia grew still flows, filling a pond in the city park. But the city tap water is apparently less than desirable. And you can still see signs on the highway for pinto beans. But mostly it’s just range land, fat with grass this year from our big summer rains, with what cattle there are gathered around the stock tanks.

There’s an old history of the valley I ran across by Bert Herrman. It quotes an old-timer by the name of Vernie Wells: “Times were hard for everybody. There might be a year or two of good crops, then the rain would stop.”