A new Stockholm Environmental Institute analysis of water supply and demand in the Southwestern United States suggests we’re screwed.

In the U.S. Southwest – Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah – there is less rain and snowfall each year than the amount of water used in the region. Today that shortfall is made up for by pumping groundwater, well beyond the sustainable rate. Add the impacts of growing population and incomes, and the Southwest will face a major water crisis in the coming decades.

But you already knew that, right? So what’s new here?

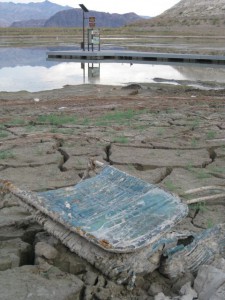

Boulder Bay, Lake Mead, Oct. 2010

I’ll stick my neck out here and argue that despite the paper’s title – “Climate Change and the Southwestern Water Crisis” – the new study’s most important finding may be that the climate change is a relatively minor player in the region’s future water problems, relative to the underlying supply-demand dynamic.

Much of the reporting the last few days has focused on the report’s dire analysis of the scale of the problem (see especially Bryan Walsh and Felicity Barringer’s nice job tying the SEI work in to a related new study on California groundwater depletion). Central to their argument is the fact that we’re using more water each year here in the southwest than nature provides, and we’re closing the supply-demand gap by mining groundwater. That’s the brickbat part of the study. But there are a couple of points that I think are worth drawing out in more detail.

The first is the connection between climate change and the underlying supply-demand problem. The authors, Frank Ackerman and Elizabeth Stanton, first calculate the supply and demand imbalance without climate change, assuming only baseline population and income growth and existing available resources. Given those assumptions, we would use 1.8 billion acre feet of water over the next century in excess of that supplied by nature, a number so staggeringly large, even for people used to thinking about big water numbers, as to be almost meaninglessly beyond comprehension.

Add in climate change (they run a couple of different emissions scenarios), and we need another 300 million to 450 million-plus acre feet. But three quarters of the problem is independent of climate change.

This is a critical point in terms of the political dynamic surrounding climate change and water in the southwest. The west’s water problems are frequently framed as a climate change problem – because of climate change, we have a water problem. Which is true. But the political dynamic surrounding climate change creates huge problems here because of the widespread climate change skepticism afoot in the land. As long as the water problem is framed as a climate change problem, then skepticism of climate change can translate into skepticism of a water problem. (Doug Kenney’s new report on Colorado River governance (pdf) has some great data from a survey of Colorado River Water Users Association that lends support to my intuition on this point.)

I would argue that Ackerman and Stanton have shown that the scale of the problem is, to first order, the same with or without climate change. 1.8 billion or 2.25 billion acre feet shortfall? Whatever, let’s get cracking!

Which is the second useful part of the analysis. OK, we’ve got a huge problem, what can be done about it?

They suggest four potential paths forward:

- increase supply (not likely, they argue, on anything approaching the scale needed)

- more groundwater pumping (what we’ve done to date, but it can’t go on forever, as the resource is finite)

- planned reductions in use

- unplanned reductions in use (eek! the pain!)

Not surprisingly, Ackerman and Stanton suggest “3” as the preferable option. Agriculture currently uses 78 percent of the Southwest’s water, while making up less than 2 percent of the region’s economy. So they argue for an orderly, planned shift from ag to municipal and industrial use:

Farming supports just 1 percent of the Southwest?s economy, and food production manufactures add another 0.8 percent of GDP. Even in California, farming plus food manufactures accounts for only 1.9 percent of state GDP. But agriculture uses 78 percent of all Southwest water, and more water will be required as temperatures grow with climate change. Extensive agricultural adaptation cannot remove all need for conservation and efficiency measures in and around Southwest homes, but it can greatly reduce the need for urban adaptation while providing an important safety net against water shortages and restrictions in dry years.

Which is both important (given the contribution offered by the rigor of their analysis and modeling) and unsurprising. A struggle over the inevitability of ag-urban transfers has long been at the heart of the western dialogue. But this begs the question of how we might accomplish this in a planned vs. unplanned way.

(h/t Keith Kloor for bringing the study to my attention)

Good point (underlying trend matters more than CC), but we know that from watching Lake Mead (don’t we?!?)

I prefer (3) as well. That’s best done by charging higher prices in urban areas (penalize lawns) and facilitating markets, both within farming communities (to identify value) and for sales to urban areas (based on higher prices).

Farmers can push for this, and better to do so before their water is taken (4).

Pingback: Tweets that mention Running out of Water : jfleck at inkstain -- Topsy.com

As always, great job John teasing out the significance beyond the initial report in the NYT. Seen any numbers on how much of Southwest agriculture, particularly Calif., is food vs. things like cotton?

I think most folks assume cutting back irrigated agriculture’s water use means less food. But given how much water cotton takes to grow in desert, it might be useful to know what percent of that 78 percent grows actual food.

Nolan – Great question. The study doesn’t pull out numbers for cotton, but they do focus on hay: 42 percent of all water used in the southwest is used to grow hay. I’m gonna talk to the authors, though, maybe for a newspaper story, and I’ll ask ’em about cotton.

I’ve seen all sorts of prescriptions – for years – that tie water use to % of economy therefore we must do away with ag.

Yeah, yeah, but we don’t pay true price for food and we pay farmers jack for their work, so that is one uncomfortable fact of our ag policy that complicates the issue.

Second, not only is the question ‘what are we going to eat’, but far, far more importantly: ‘where are we going to grow the food if CA production goes away’?

Sorry to bring this up, but is there another Salinas Valley lying around somewhere that I don’t know about? Another Central Valley (not Valle Central)? Don’t tell me Chile because they have the same climate regime as California, their seasons are reversed to ours, their water situation is not much better, and in a few years we won’t be shipping stuff on a whim, willy-nilly all over the place.

It is facile to assume CA is substitutable. And simply throwing out numbers out of context is a poor way to frame the issue for future policy.

That is: IMHO the situation is neither being framed nor addressed honestly. As it is with so many things in CA.

Best,

D

Dano’s right: framing this as Ag vs. Urban is completely inappropriate. The fact is that all users are going to have to reduce consumption while maintaining productivity. There is currently plenty of opportunity to do that, but David Zetland is also correct: pricing and market limitations currently provide few, if any, incentives for conservation.

Congress and USDA need to be involved in fixing this situation. (There’s your cause for pessimism, if you needed more.) Federal ag policy subsidizes the wrong crops and the wrong practices.

Dano gets a little off, though, when he implies that SW ag is all about food crops. Even in CA the proportion of water used to grow non-food crops like cotton or hay (alfalfa is grown largely with mined groundwater) is very large. Markets (or subsidies) could provide opportunities to change that, if food crops increase in value.

I’d also like to chime in on the inappropriateness of framing this in terms of ag v. urban, largely because the relationship is uneven, i.e. small reductions in ag use can enable large increases in urban use (with accompanying increases in efficiency). The issue is whether we can plan for a future where the appropriate amount of water is allocated to ag and appropriate amounts are allocated to urban. This would require actually planning what type of ag we want and how much, as well as what kind of population growth we want and how much. Not to three significant figures, necessarily, but sensible, supportable estimates. This is logistically and politically challenging, but still do-able. Just requires the political will and the necessary policies in place.

Tim, I thought about mentioning dairy & beef in the SJV, but then you are talking about me ranting about big dollars, and folks like Westlands getting grumpy and unleashing lobbyists, so I just skipped it.

But that is a large part of the problem, absolutely agree. And also the issue of such a large fraction of our food and economy coming from a Mediterranean climate (same climate as in Chile, BTW)…

Aside but relevant, our recent snow just prevented me from paying about $6000 to have our District’s landscaping company water in the winter, due to our drought and inappropriate landscaping (acres of bluegrass turf… |: ( ). Lots of room for conservation on all fronts [not that my District has the money to retrofit any time soon].

Best,

D

Agriculture and ranching will need to be appropriate to the water supply, and we will need to factor the true and rising cost of water into the cost of agriculture without subsidies. It’s not that there can’t be agriculture in the Rio Grande Valley, but we need to cultivate low water crops–not cotton–that are suitable to the conditions.

These will be difficult changes because of the out-sized lobbying presence of farm and ranch in the West.