update: Michael Cohen at the Pacific Institute emailed with a subtle clarification. If Lake Mead, as the USBR analysis reported below suggests, drops below elevation 1,075 feet above sea level during 2015, the actual shortage declaration on the lower Colorado would then apply to the following year’s water allocation. More specifically, during August the Bureau looks at the projected Jan. 1 storage, and if that’s below 1,075, the shortage is declared. Historically, about half the time Lake Mead has been lower Jan. 1 than the May number. This means we could have the shortage declaration in 2015, but the actual shortage wouldn’t kick in until calendar year 2016. Correction appended below.

previously: There was a round of press coverage last month (including from me) when Mike Connor, head of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, told reporters that internal Bureau modeling suggested as much as a one-in-three chance that Lake Mead would drop so low by 2016 that the federal government would make the first ever formal shortage declaration on the Colorado River.

New data out yesterday suggests that may have been too optimistic. The latest operational report from the Bureau now suggests a good chance of hitting the shortage trigger by mid-2015. Arizona and Nevada take the hit, and it’s a small hit initially, but it grows as Mead drops further.

The latest monthly modeling report (the Bureau’s much-read 24-Month Study) now suggests Lake Mead’s surface elevation could drop to 1,075 feet above sea level – the level at which a formal shortage declaration is required – as early as June 2015. As I understand the rules, this would likely could mean a reduction in water deliveries (initially, a small reduction) beginning in the fall of 2015 calendar year 2016.

Actually, it doesn’t exactly say we’ll be under 1075 in June 2015. The 24th month of the study (remember the name – it’s a 24-Month Study) is May 2015, at which point the Bureau figures Lake Mead’s elevation will sit at 1,075.28 feet above sea level. That’s 3 inches – the wake of a slow boat – above the drought trigger. But given that Lake Mead’s always dropping at that time of year, one can reasonably project that, if reality follows the trajectory of these projections, it’ll be below 1075 come June 2015 – a year earlier than the model runs Connor mentioned to reporters just a month ago.

So what’s different?

The answer, I’m told by Bureau staff, is a change in the approach to modeling the supply side for the out years in the study. In the near term, for the current year, the Bureau uses forecast model data from NOAA’s Colorado Basin River Forecast Center. For the latter part of the 24-month window, the Bureau would then just plug in average month-by-month data, essentially presuming the out-year periods were “normal”.

But starting this month, the Bureau switched to the use numbers from one of the CBRFC’s long-range forecast models, which seems to be much more pessimistic than the old “normals” used in the May 24-Month Study. The modeling switch, combined with some water management spare change (differences in Grand Canyon inflows, a change in the Metropolitan Water District’s operating plans) has resulted in a ginormous 2 million acre foot drop in total storage in Lakes Mead and Powell in mid-2015 between the May and June 24-Month Studies.

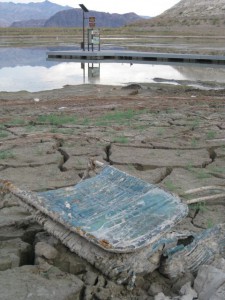

My picture, above, was taken in October 2010, when Lake Mead was in the low 1080s.

Pingback: River Beat: June numbers show slight improvement in Lake Powell : jfleck at inkstain

Pingback: Drought/runoff news: Dillon Reservoir is close to filling, Standley Lake operationally full as of last Tuesday #COdrought | Coyote Gulch

Pingback: A Few Good Reads (6/17/13): What Next in Germany? 2012 Second Costliest Disaster Year in U.S. » Hydraulically Inclined