A new analysis suggests Lake Powell could crash in less than three years if there were to be a repeat of drought (aridification?) conditions seen in the recent past.

While the basin community’s attention has been focused on the risk of Lake Mead plummeting at some point in the future, Lake Powell at the bottom of the Upper Colorado River Basin is likely to drop 32 feet this year. This is happening in the Upper Basin now, and a couple more drought years could make it scarily worse.

32 feet in Powell is 3.2 million acre feet of water – equivalent to more than an entire years’ use in the Imperial Irrigation District, the largest water user in the Colorado River Basin.

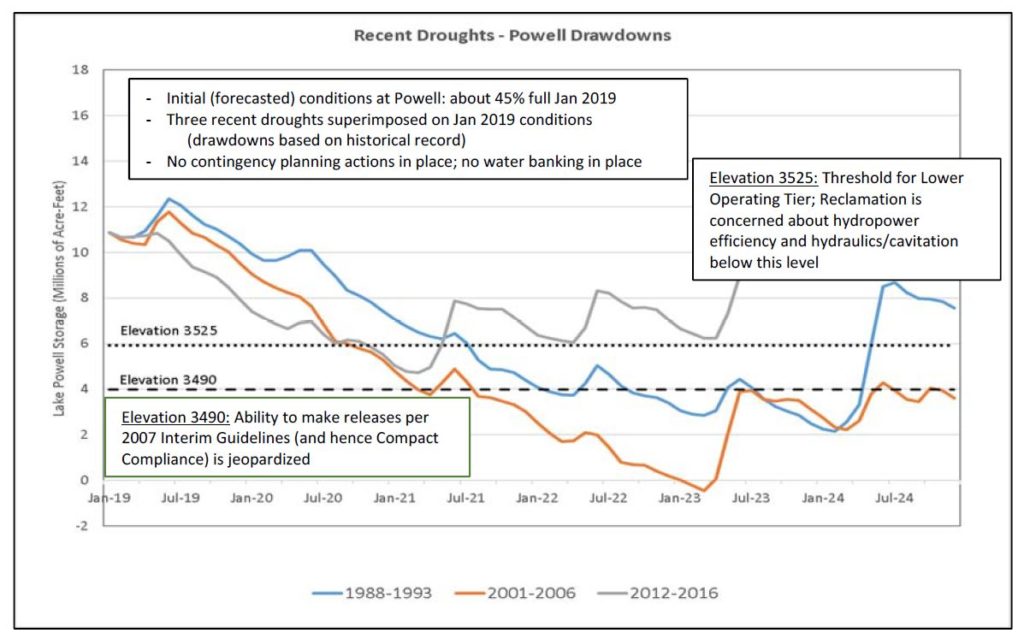

Some work done as part of a new analysis being done by The Nature Conservancy (shared here with permission) shows just how quickly Lake Powell can crash. While discussions about risks to Lake Mead hinge on complicated water policy discussions, the crashing of Lake Powell can be the result of simple hydrology. Simple very bad hydrology that is. But we don’t need scary worst case tree ring stuff or hypothetical climate change hydrology. We just need a repeat of any the three most recent droughts in the last three decades. That’s a discomforting “return interval”, to use the hydrologist lingo.

The difference is that the last three times, the droughts happened with relatively large reserves in the reservoirs. That cushion is gone:

Crashing Lake Powell. Courtesy TNC.

This is the explanation for the “how to crash Lake Mead” graph from U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman I wrote about yesterday. That orangy line in the TNC graph models the same period as Burman’s “crashing Lake Mead” graph from yesterday’s post – a repeat of the drought years of the early 21st century. As the levels of Lake Powell decline, under the operating rules less water will be released from Powell into Lake Mead. So as Powell crashes, Mead crashes with it. These two reservoirs, and therefore the fates of water users in both basins, are inextricably linked.

Elevation 3,490 in Lake Powell doesn’t get the same amount of ink that 1,075 or 1,050 or 1,020 in Lake Mead get. But it’s an equally scary proposition. 3,525 is kind of a safety line, like 1,075 in Mead. Below that, we should be very nervous. As the graph in the TNC analysis points out, at 3,490 “Ability to make releases per 2007 Interim Guidelines (and hence Compact Compliance) is jeopardized.”

Pingback: Blog: How to crash Lake Mead: Step 1 — crash Lake Powell | H2minusO Blog