Here is some data about Lake Powell, the big Colorado River reservoir straddling the Arizona-Utah border.

- Since 2005, the average estimated “natural flow” of the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry has been 13.5 million acre feet per year, well below the 14.8maf average since 1906.

- So yes, it’s been dry.

- Since 2005, releases from Lake Powell have exceeded the Upper Basin’s Colorado River Compact and Mexican treaty obligations by 9.4maf.

- So despite the fact that it’s been dry, we Upper Basin residents have had enough extra to deliver a bunch of “bonus water” to downstream water users.

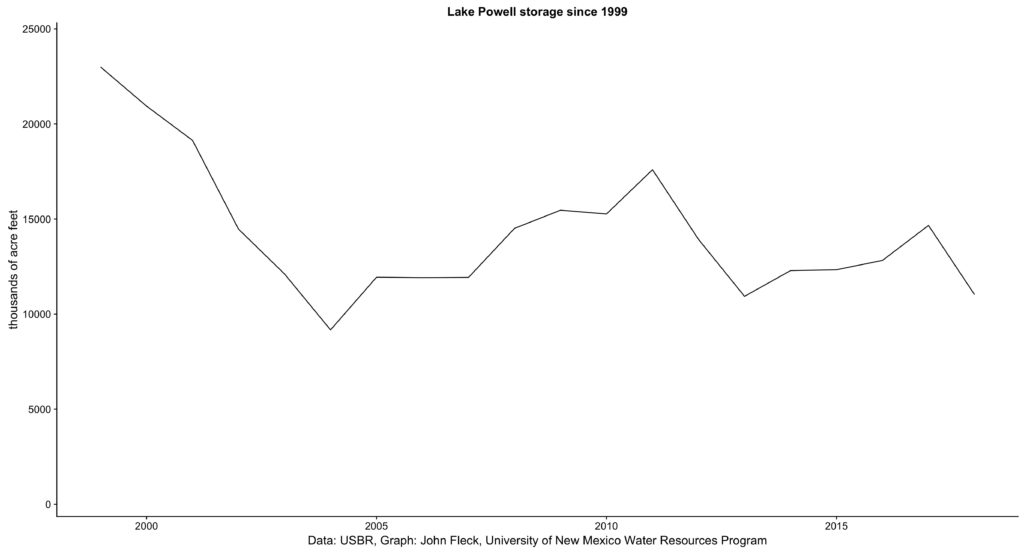

- Since 2005, the total volume of storage in Lake Powell has risen, from 9.169 million acre feet at the end of 2004 to 11.028 million acre feet at the end of 2018.

- So despite being dry, and delivering extra water downstream, Lake Powell’s elevation has been relatively stable.

This is straightforward empirical stuff.

Brian Maffly has a great piece in the Salt Lake Tribune about the challenges of Colorado River management, with a focus on Lake Powell.

But Maffly weakens an otherwise excellent survey of the river’s issues with the alarmist assertion that “without a change in how the Colorado River is managed, Lake Powell is headed toward becoming a ‘dead pool.'”

It is important when doing journalism about phenomena over time (and any other sort of analysis) to choose periods of record that accurately capture the thing you’re trying to understand and explain. Maffly, and the sources on whom he relied for the story, have cherrypicked a time window that supports the “OMG POWELL DOOMED” argument, but that is misleading.

In support of his argument, Maffly notes that Powell “has shed an average of 155 billion gallons a year over the past two decades.” That is correct, but it’s a troubling choice of time frame. Since 2000, Maffly writes, Lake Powell “has been steadily dropping.” This is false.

The entire loss Maffly describes happened during the first years of the 21st century, the driest five-year stretch on record. Yowza, Lake Powell dropped a lot during the drought!

From 2005 to the present, Lake Powell’s elevation has been relatively stable, not steadily dropping.

Lake Powell storage since the turn of the century

It certainly would be correct, and is important to note, that a repeat of the drought of the early ’00s would be disastrous. Absent changes in management, it would lead us to dead pool. It is important to have policies in place that are ready for that. Increased withdrawals from the basin increase the risk should that happen. But the years that followed the drought of the early ’00s, in which Lake Powell’s levels have been stable despite a river flow depleted by climate change and the crazy policies that continue to ensure excess downstream deliveries, also are important if we’re to assess the impact of current Colorado River operating policies on the risk of Lake Powell reaching dead pool.

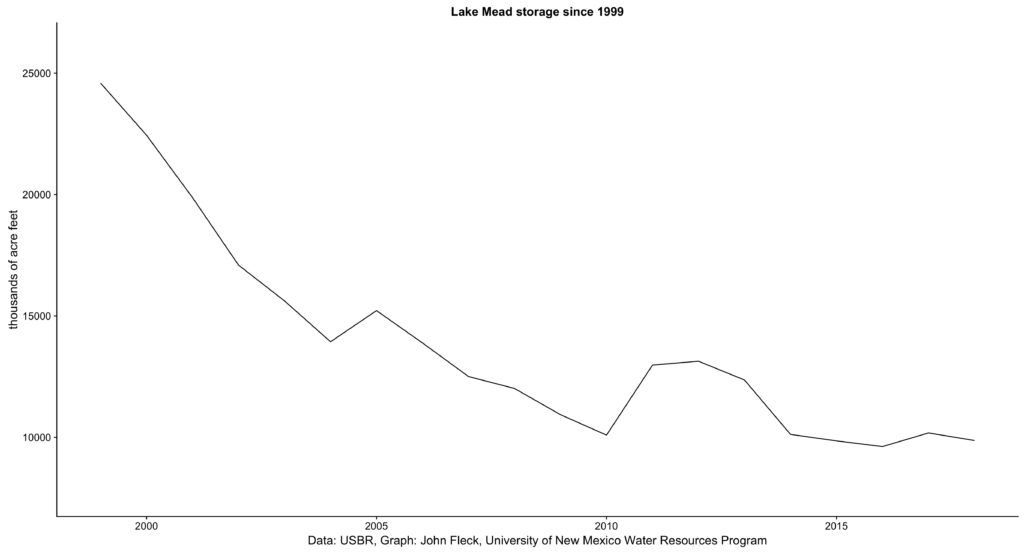

The reservoir that seems to be headed far more inexorably toward disaster is Mead, not Powell. That’s a lot closer to what I imagine when I hear “steadily dropping”. Remember that Mead is declining despite deliveries since 2000 of more than 9 million acre feet above the Compact-Mexico obligation of 8.23maf per year.

Lake Mead storage since the turn of the century

To be clear, I believe the Colorado River faces serious challenges. I agree with Doug Kenney, who told Maffly, “At some point, you can’t ignore reality anymore, and the reality is we need to use a lot less water in the Colorado Basin.” Yup. Doug’s right. This includes the Upper Basin. The Lake Powell pipeline and other efforts to take more water from the system seem ill-advised, guaranteed to increase the risk to existing users in both the Upper and Lower basins.

Much of the challenge right now, though, is in the Lower Basin. The ability to maintain Lake Powell’s elevations over the last ten-plus years despite drought and “bonus water” releases from Powell suggests the Upper Basin is in a far better position.

Much of Maffly’s discussion of the overall challenges is excellent. It’s important, especially for Utah water users to hear. But selling that message with “OMG LAKE POWELL DEAD POOL” is at odds with the facts, and undercuts the otherwise important stuff the story has on offer.

A note on data sources:

- Lake Powell storage data is here from USBR, I’ve posted a slightly easier to use summary here.

- Data on Powell releases can be found in the annual USBR accounting reports.

- Average annual flow at Lee’s Ferry is in the USBR Natural Flow Database, with estimates for more recent years via personal communication with USBR.

That said, unless the old Compact is junked entirely, or other things, or whatever, do you believe that Lake MEAD is “inexorably” headed to dead pool? Along with James Powell, I do, on the basis that one or the other of the two lakes HAS to go that way. And, it ain’t gonna be Lake Powell, for political reasons alone.

I don’t. One of the core arguments in my book is that when people have less water, they use less water, and that communities have demonstrated over and over that they can survive and even thrive with a lot less water than they use today. We don’t do it until we have to, but then we do it pretty well.

Wait … derp, I got my lakes backward! I know what your data says, but the lower basin ain’t letting Mead go dry for political reasons. And, James Powell I am pretty sure has it right, that it’s one lake or the other. Mead is not being let die by California, etc.

Oh, and water banking anywhere on the river is as fictitious as saying the war in Iraq is off-budget spending. And, contra US dollars, nature bats last.

I do know that the lower areas are using less water … but that’s being partially offset by drought and increased evaporation, which will only increase in the future. And, as the upper basin gets warmer, to flip Marc Reisner on his head, there may be an increased call for ag water up there.

And, as long as the “solution” involves fictitious water banking, that part of it is simply not an actual solution. So, one lake or the other’s going to hit a real problem point in the future, and politics says it will be Powell. It may not fall all the way to dead pool, but a drop to “power pool” seems very likely. Again, politics involved. LA electrical users, especially with California pushing harder than Arizona to go greener, have more sway.

I don’t think we have the political will to avoid this emergency. Mother Nature and the good Lord will rule as we sit on our hands

See also https://e360.yale.edu/features/on-the-water-starved-colorado-river-drought-is-the-new-normal

Pingback: Again the question about whether Lake Powell is doomed |

Per what I said about “power pool” and electricity, it seems like there’s a LARGE amount of silence on this. If Powell hits power pool, there’s a lot of electricity it has to go find. It also impacts Utah’s plans to pump water to St. George.

Per Wally Mac, nature bats last, and sorry, Fleck, per things like fictitious water banking, I doubt the will is there for real changes. The planned updates to the Compact with the Jan. 31 deadline are themselves halfway out of date as we speak.

I wholeheartedly agree with this entry. Lake Powell isn’t the problem, it’s not going anywhere anytime soon. The problem is with Lake Mead and (1) its over allocation, (2) the fact that lower basin states aren’t charged for evaporation and the lower basin’s contribution to Mexico, and (3) the lower basin’s over allocation of its basis 7.5 maf. To make matters worse the DCP doesn’t really do anything to address any of these problems.

In other comments, I have stated that the lower basin needs a minimum of 9 maf from the upper basin annually. This was an attempt to point out how absurd the allocation numbers of the lower basin are, and how something should have been done about this many years ago. The problem still exists, and is made worse by an interim agreement which punishes the lower basin for conserving water (and, thus, not receiving bonus water on years which there is some).

Something drastic needed, and still needs, to be done, and the only answer certainly isn’t the DCP (far from it). Until this happens, if it happens, Lake Mead is the reservoir at risk of crashing.

jfleck wrote above, “We don’t do it until we have to, but then we do it pretty well.” Previously, this has been the case more often than not; however, now is the time we really really really have to, and we are pretty darn far from doing it pretty well! Time will reveal how this plays out, but looking at what’s currently taking place, I’m not all that optimistic.

Charles, I’m pretty sure the upper basin isn’t charged for evaporation at Powell, either. How would you assess that, with either reservoir? So, that part is a red herring.

As far as what’s arguably the best usage? Other than continuing cutbacks everywhere, and more water-wise crops on the ag side, Marc Reisner nailed it decades ago: It’s too dam(n)ed cold to grow too dam(n)ed much in most the upper basin.

Beyond that, arguably, the old framework is dead. Within the upper basin, Wyoming/Green, Yampa/NW Colorado and Duchesne/NE Utah are the most “challenged” on ag and the lowest population. Subdivide the Upper Basin in half, ignoring state lines, where the Green exits Dinosaur. Then “extend” the lower half of the Upper Basin to Hoover Dam instead of Lee’s Ferry. Retabulate flow rates for the basin to today’s reality, then subdivide unequally per usage reality into three parts.

(Reality? With the existence of a United States Senate, this will never happen, of course.)

Beyond all this, per Dan Beard, Glen Canyon Dam is quite arguably a “deadbeat dam.” https://www.hcn.org/articles/deadbeat-dams-bureau-of-reclamation-beard

Per my one comment above, which only covers the Green, the upper reaches of the Colorado above Grand Junction could be hived off as a top basin suggestion.

Or, if not intrusive to the National Park Service, put the upper basin from the Confluence and above, with a gauge there. Would be easier than having upper Green and upper Colorado separate. Middle basin down to Hoover Dam. Lower basin down to the border. Use BuRec river basins to determine appropriation.

In either case, this does the reality of pairing Powell and Mead in legality.

SocraticGadfly –

Red herring? I think not! I believe (read: not certain) the upper basin states are charged for evaporation on Powell, but whether they are, or aren’t, is moot. Why? Well, because they don’t even use 2/3 of their 7.5 maf annual allocation; thus, an annual (structural) deficit does not exist (thankfully) in the upper basin. It’s Mead with the structural deficit problem, and, as such, the onus lies on the lower basin states to fix it. I have argued previously that the entire system needs to be viewed as one system. This then could potentially redistribute the burden(s) to benefit everyone involved. However, to say it’s doubtful that will ever happen is being way too optimistic! So, back to reality, the lower basin needs to fix the structural deficit, and its over allocation of the original 7.5 maf ASAP (should have been done years ago). The only way I realistically see it happening (at least anytime soon) is to charge the lower basin states for their share of evaporation (which is reported by USBR), and also the lower basin’s share of Mexico’s water. This might not solve the entire deficit, but it will come close. IMO, this is a much better starting point than the ridiculous DCP.

As for a new framework, I (along with a friend) have played with a handful of different models, and have come up with ones which, we believe, would manage the river better than what is taking place under the ’07 Interim Agreement. That said, mine, yours, or whoevers has very little chance of ever coming to fruition. We can debate the potential benefits of radical new frameworks, but that too would be moot. The main problem isn’t the US Congress (specifically you mentioned the Senate), but a little thing called The Law of the River. Then too there is the issue of the Secretary of the Interior not stepping up and taking charge until now (if you consider a DCP deadline taking charge).

As for Beard, I’m not on the same page there. I didn’t agree with much he said when he was the Commissioner, and agree with even less of what he says now.

Charles, I’ve played with models before, too. I’d prefer to throw out the current upper/lower basin.

I referred to the Senate because of Congressional action possibilities and the equal apportionment Senate. That itself is relevant to the original Compact as well as everything else that makes up The Law of the River. After all, many of the actions that follow on the Compact itself are acts of Congress. And, of course, SCOTUS in the 1964 ruling.

There’s also “common law” if you will, such as Arizona’s “war” over lower basin appropriation before having to pull in its head.

As for DOI taking charge?

This is ultimately a matter that needs legislation — or will get court action at some point.

And, DOI screwed the pooch when it gave Arizona 37 percent of the lower basin in the first place.

SocraticGadfly, Please don’t infer that I think that DOI is the answer to all of the river’s problems. Nothing could be further from the truth. I’m not a fan of big government attempting to manage these sorts of things. However, with all the states in the mix, there really isn’t any other way. DOI has the ability to step in and put pressure on the states (as shown by the current leaning on AZ) so it’s about time they stepped up to the plate and started exerting some authority to keep everyone in line.

The solution to the Colorado River water shortage is for SoCal to build desal infistructure and stop pulling water out of the Colorado. The cost would be shared by all users (including CA) since this would benefit all.