Putting in downstream from the Taos Junction Bridge. June 8, 2019, photo John Fleck

TAOS JUNCTION BRIDGE – I took back roads upon back roads this weekend to get home from Boulder, where a bunch of us had gathered for three very socially and intellectually intense days talking Colorado River stuff.

I ended up on one of those “what happens if I turn here?” digressions, off US 285 onto NM 567/570 (I’m confused about the numbering). The road drops via zany unpaved switchbacks onto the Rio Grande in Taos Gorge, crossing at Taos Junction Bridge, circa 1930.

I stopped for a few minutes at the boat ramp on the far side of the bridge, lurking and watching as happy families rigged their boats for a float down a pretty robustly flowing Rio Grande. It’s the biggest flow at this point in the year since 1997. After three days of thinking about water management at the scale of the entire Colorado River Basin, it was a great reminder that at its root all water – this day, this river, this reach, these families – is local.

Sort of.

As I was leaving the University of Colorado School of Law Friday afternoon, headed for the San Luis Valley near the Rio Grande’s headwaters, one of my friends said, “Buy up all the water rights you can!”

My friend’s crazy scheme is that “we” (someone, who?) should buy up water rights in the San Luis Valley and retired them. The water would be sent down the Rio Grande to Albuquerque, which could use it in lieu of importing Colorado River Basin water via the San Juan Chama Project.

This is of course a crazy scheme. I first heard my friend float it over breakfast at a meeting in Phoenix. Sitting at the table with us were a couple of senior water managers from Arizona and Colorado. They noted that, what with interstate compacts involved (one on the Rio Grande, a second on the Colorado), this would be a tricky transaction that their states would have to approve, but would not look upon kindly. And of course the good folks of the San Luis Valley might have something to say about this as well.

As I said, it’s a crazy scheme. But as Utah State’s Jack Schmidt said during a talk Friday in Boulder, we stand on the shoulders of some pretty crazy schemes in the Colorado River Basin.

On the drive Friday to Alamosa in the San Luis Valley, I passed one of them, the outlet of the Roberts Tunnel, which diverts Colorado River Basin water 20-plus miles beneath the Continental Divide dumping it into the North Fork of the South Platte (yeah, they really call it that) for use in Denver.

US 285 climbs out of the South Platte drainage, eventually crossing into the Arkansas River Valley. By the time the highway joins the Arkansas at Buena Vista, that river has already been augmented by another transbasin diversion. The Fryingpan-Arkansas Project (“Fry-Ark”!) takes water from the headwaters of the Fryingpan, a tributary of the Roaring Fork, which is in turn a tributary of the Colorado.

Standing on the shoulders of crazy schemes, as Jack said.

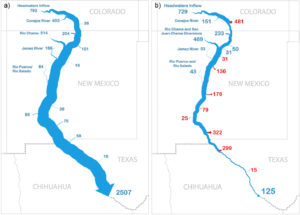

Blythe, Todd L., and John C. Schmidt. “Estimating the Natural Flow Regime of Rivers With Long-Standing Development: The Northern Branch of the Rio Grande.” Water Resources Research 54.2 (2018): 1212-1236.

As I stood at the Taos Junction Bridge this morning watching families rigging boats, the Rio Grande was flowing at about 3,700 cubic feet per second. Given that, as I said, it’s the most at this point in the year since the late 1990s, it feels to us like a lot of water. But up in the San Luis Valley, a lot of water is being diverted right now for farming. At Del Norte, where the Rio Grande enters the San Luis Valley, flows today were more than twice that which finally reaches Taos Junction Bridge.

Jack and one of his students, Todd Blythe, published a neat paper last year trying to estimate how much water would be flowing down the Rio Grande absent upstream dams and diversions. In the stretch I visited today, they concluded, modern flows are about half what flowed before we started all our crazy schemes.

The result of all these crazy schemes is that no water is ever really local. But one of the corollaries of my friend’s admonition to buy up San Luis Valley water rights is that less land in the valley would be farmed and more water would flow every year past the Taos Junction Bridge.

In essence, then, no water is really local. It’s all interconnected.

” IT IS A COMMUNITY that’s inextricably linked to one another. It starts in Cheyenne, Wyoming, finds its way to the Front Range and the Platte user community in Colorado, winds its way to the Wasatch Front in Utah, goes over to the east to the Rio [Grande] community in New Mexico, winds its way across the Arizona desert, to the inland cities of Arizona, and then when it touches California, it doesn’t stop in southern California. The interconnection permeates all the way up to the Bay Delta. We’ve all become interconnected by users that share resources in various directions. So what happens in one area affects another area. And it affects it with great magnitude.”

–Pat Mulroy

“In 2012, the drought-stricken Western United States will ship more than 50 billion gallons of water to China. This water will leave the country embedded in alfalfa—most of it grown in California—and is destined to feed Chinese cows. The strange situation illustrates what is wrong about how we think, or rather don’t think, about water policy in the U.S.”

— Peter Culp and Robert Glennon, the Wall Street Journal

U took a good route

Good to see u in boulder

Thanks

What “rights”?

Over decades, immigrants to the region assigned themselves portions of the waterways to further their own livelihoods. The rivers seemed limitless. Who knew about the Anasazi? We’ve come a very long ways from a few gardens, hayfields and water wheels. We’ve changed the landscape in ways no one could have imagined.

The planetary limits (what?) now constrain us to change our own creation in ways that might allow some of us to stick around. Interstate compacts are going to be redone. “Rights” will be redefined. Assumptions will be changed.

Or else.

John: No need to buy water in Colorado. If any communities downstream of Colorado would like to buy some, we have a lot to sell. Colorado will charge $50 per acre foot exported.

One of the amazing things to consider is that here in Arizona, the Hohokam and the Ancient Pueblans built great civilizations and, in the case of the Hohokam, 100s of miles of canals. They thrived for 1000 years and were successful even with the varied flows of the rivers.

1000+ years.

We here in Arizona are looking to suck down our aquifers in less than 300. The DCP shows how much we over allocate all our surface water, not just the Colorado. Millions of years to fill these basins and 100s of years to empty them.