Since early spring, I’ve taken my early morning bike ride through downtown Albuquerque to the old Route 66 crossing of the Rio Grande. Every time, I’ve stopped to check out this little sandbar island, anchored by a tenacious community of willows. I started watching closely after I saw a pair of geese, frantic as the water rose to cover their nest.

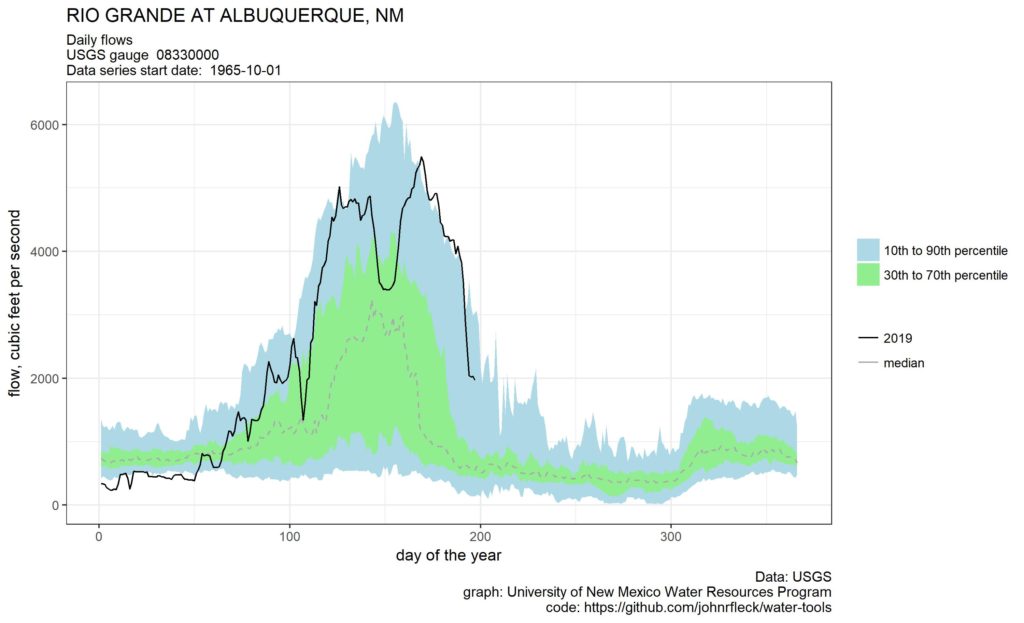

For much of the last three months, the exposed sand you see here was covered in water, as we’ve seen the highest flow past this bridge since 2005.

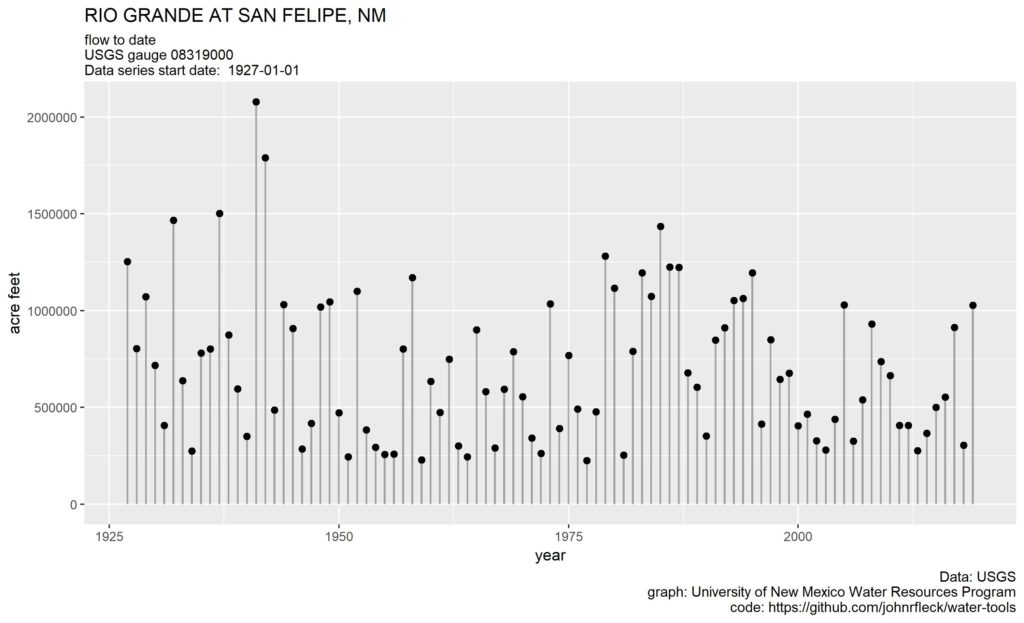

The flows here are attenuated, in part because Albuquerque’s municipal system takes water upstream of this point. But up at San Felipe, where we have a good gauge and a long record, we’re on track to record the biggest flow into this reach of the Rio Grande Valley since 1995.

Every time I’ve been down, I’ve wondered if my little island would be gone. But this fascinating partnership of sandbar island and willow off the Central Avenue Bridge persists, emerging the past few trips as flows dropped below 2,000 cubic feet per second for the first time since early April.

Scholars have helpfully defined resilience as “the ability of a system to survive a shock while retaining its basic structure and function.” One of the important issues when invoking the resilience framework is what we include within our definition of the “system” (“Resilience of what, and for whom,” as my friend and colleague Mindy Benson frequently asks.). If our definition is to include the geese, my little island has failed the resilience test. But if we’re talking about the partnership of sandbar and willow, the basic structure and function remain intact.

This is an excellent example of how natural systems work, that is, the sandbar and the willow. It appears from the picture that flow is from right to left (?), just looking at ripple patterns around the sandbar/island and at the bridge supports and baffles. The root structure of the willow is binding the soil and keeps the willow/sandbar system in tact, resisting flow from the right, and forming the downstream taper as the root system appears less dense on the tapered, downstream, pointed side of the sandbar. “Bioengineering” borrows from this concept; for example, in designing a bioengineered structure, willows poles are planted in a riprap, inline grade control structure, with the intent of having the root system bind the riprap and willows together, ultimately forming a stronger structure. During large flood events, the willows lay over in the direction of flow, hopefully keeping most of the rock in place.

The use of willows to stabilize islands and river banks was first documented in Roman times. It is called “willow spiling” and was practiced throughout the Roman Empire. It is easily viewed along the upper reaches of the Thames River in England. I made a trip to the UK in 2009 specifically to view this practice foolishly thinking that the MRGCD might adopt it to stabilize their ditches and canals which were especially affected with the high flows this year. It is a cheap and effecting method.

Search for “willow spiling” using your favorite search engine.

Ah, beautiful. Talk ecology to me, baby