Imported Colorado River water flows down the Rio Grande. Albuquerque, New Mexico, June 19, 2020

Faced with the challenge of teaching some or all of our coursework this fall on line, my University of New Mexico Water Resources Program colleagues and I have been having a think about what we’re trying to accomplish.

A lot of the thinking revolves around translating our educational goals from face-to-face classroom discussion to the new “modalities”, as the current edu-speak puts it. But it’s a useful moment, as I head into my eighth fall teaching , and my fifth as the program’s director, to also have a think about the underlying goals.

Tradeoffs

As is my way – always, but more so in the Time of Pandemic* – I had occasion to stop on Friday’s bike ride to look at the Rio Grande south of the Albuquerque’s old Route 66 bridge.

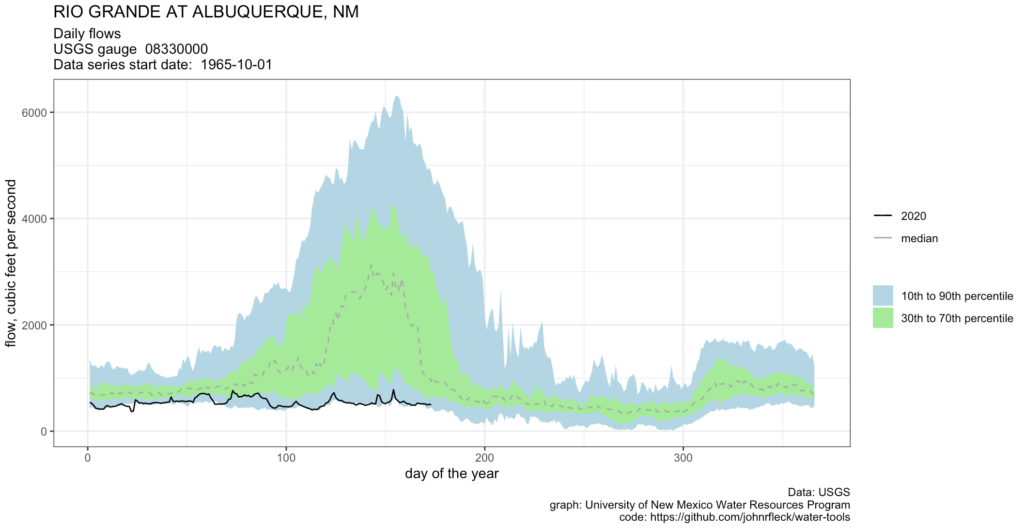

The flow’s been hovering around 500 cubic feet per second, which is low for this time of year. It is what we’ve come to call an “institutional hydrograph”.

2020 runoff on the Rio Grande – a year with no spring pulse

The hydrograph is a familiar graph to folks in water management (or studying it!) – time along the x axis, flow on the y axis. The graph above is an example of my attempt to place the current year (the black line) into historic context. We’ve had a gauge at the Central Avenue Bridge since the mid-1960s, and you can see the “normal” pattern: low flows through the winter, then more water in spring as the mountain snows melt.

This year, not so much.

A look at the gauges upstream tells the story: almost no natural flows coming into the valley from either the Rio Chama or the main stem of the Rio Grande. Almost all of the water flowing into the valley right now is coming from storage in El Vado and Abiquiu reservoirs, and a big chunk of that is Colorado River water, imported via the San Juan-Chama Project.

We call it an “institutional” hydrograph because of the role of water management institutions in shaping it. We write rules, create government agencies to implement those rules, and through those government agencies build physical plumbing to move water. The rules both create the plumbing, and create the decision-making framework for determining how much water moves through it.

The rules are how we mediate the tradeoffs.

In this case, the set of rules that determine flows in the Colorado River – the 1922 Compact, the Upper Basin Compact, the Colorado River Storage Project Act – both enabled construction of the San Juan-Chama Project and determined how much water we would move through it. The water is then handed off to more rules that govern Rio Grande water allocation and delivery, along with the plumbing that brings some of that imported Colorado River water to my home and garden.

And, in the process, keep some water flowing past the Central Avenue Bridge.

* I checked my Strava maps – three bike rides to the river last week, eight total crossings. It has to be an even number or I’d never get home.