Lissa, an able book research field assistant (by which I mean she happily listens to my yammering, asks the best questions, and indulges the vital forays into the field to see stuff), joined me on a drive yesterday afternoon to the Barelas Bridge, one of seven Rio Grande crossings in the river’s Albuquerque reach.

There’s an odd little cluster of buildings on the bridge’s west end that look a little bit like an old roadside motel, but older and smaller and somehow more puzzling. Also, now, boarded up.

1931 Sanborn map of west end of Barelas Bridge, courtesy Library of Congress

The 1931 Sanborn map of Albuquerque (am I the only one who spends evenings lost in the Library of Congress collection of Sanborns?) describes it as a “tourist camp”. They began sprouting up along the nation’s developing network of “highways”, as auto tourists began spreading out across the country. I first ran across a reference to them in a lovely little bit of work by Van Citters Historic Preservation, a review of the area done as part of a Bernalillo County public works project:

[I]n the mid-1920s, as automobiles became more accessible to the American public and recreational travel grew, many small, private, locally owned “tourist camps” were being built on US 85 and 66 both on the outskirts of Albuquerque and along those corridors within town. Tourist camps typically a collection of stand-alone structures or rooms that would be rented for the night and often had communal bathrooms and kitchens (although the earliest tourist camps consisted of actual camp sites in public parks). Over time they became known as “tourist courts,” and after World War II they were typically under a single roof and began to look more like modern motels. In general, these camps operated well into the 1960s. They provided an increasing array of amenities, such as heat, electric fans, and private bathrooms and kitchens.

In 1931, the Sanborn maps identify six of them along the streets that made up the western approach to the Barelas Bridge, along with filling stations and an auto repair shop. By the 1940s, they dominated the area’s streetscape economy.

I’m down this rabbit hole because, for the new book, Bob Berrens and I are trying to run make sense of how Albuquerque as a community solved the many collective action problems posed by living on the floor of a river valley. Nothing unique to Albuquerque. To quote Steven Solomon:

How societies respond to the challenges presented by the changing hydraulic conditions of its environment using the technological and organizational tools of its times is quite simply, one of the central motive forces of history.

We’re mostly thinking about the challenges around that time period posed by the need for flood control and drainage, and to a lesser extent irrigation. Those will almost certainly be the primary focus of the book. But bridges! Such a fascinating collective action problem, in the time when the whole idea of collective governance at the city scale was being invented.

Barelas was an oft-used ford across the river until 1898, when the first bridge was built.

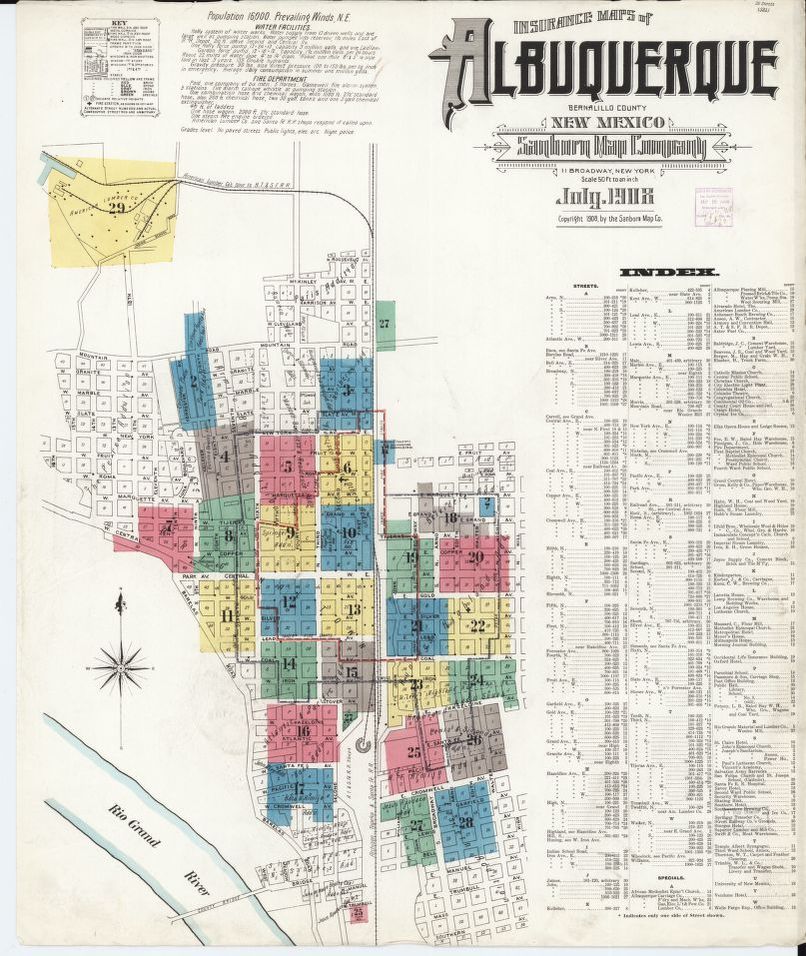

The 1908 Sanborn map of Albuquerque includes what at the time was the major Albuquerque crossing of the Rio Grande in the Albuquerque reach, simply labeled “County Bridge”.

It connected the villages of Atrisco on the river’s west side to the city’s downtown and, importantly, the yards of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad – the valley’s major employment center.

Santa Fe New Mexican, Sept. 5, 1907

At that time it was mostly wagons that used the bridge – and sheep – Bob found the excerpted newspaper story to the right, from the Santa Fe New Mexican. 23,500 sheep! (Lissa: “I wonder how many dogs that took.”)

But as the newspaper coverage of a 1912 washout made clear, the Barelas Bridge was a vital piece of community infrastructure.

The County Commission gave Herculano Garcia permission to operate a temporary ferry under the condition that he not charge more than 5 cents per passenger.

Alfalfa crops on the west side of the river sat, “spoiling on the ground” (ABQ Morning Journal, June 28, 1912) unable to get to market.

But most importantly, perhaps, for the city’s economy, railroad workers who lived on the Atrisco side of the river couldn’t get to work.

The back-and-forth over fixing the bridge, as with much of what was going on in Albuquerque at the time, suggests that providing the infrastructure needed for a growing city was the core collective action problem the community faced.

I’m still sorting out what happened next, but I think we’ve got a classic case here of other people’s money. It’s a theme in all these stories – as with much of the developing West, Albuquerque never quite could afford the stuff we needed to graduate to city-ness, so we turned to the federal treasury for help. More work needed here, but I think the key is the 1916 Federal Aid Post Road Act, which provided federal matching money for stuff like highways and bridges.

Not sure where all of this goes. I remain fascinated by bridges as an example of collective action problem-solving, though it’s orthogonal to the main “drainage and flood control and sorta irrigation a little bit” theme of the book.

I have always been amazed how many bridges built during the Roman Empire are enduring infrastructure still in use today, especially in France & Spain.

John: NIce piece today. We have used the Sanborn maps for many years in conducting Phase I environmental site assessments. They were used by insurance companies back in the day to determine rates.

Rhea

CCC and WPA bridges and sidewalks are faling into disuetude. Roman engineers used pozzolinic or hydraulic cement on many of their projects and as you note the bridges (and aqueducts and harbor infrastructure, and buildings) are still there. Reason? Pozzolinic cement is a high silica cement originally made with ash from Mt. Vesuvius. It forms stong cross-linked minerals and does no shrink and coes not crack. I tried to get the MRGCD to use it when they grout large ditches. No such luck. I use it to shut of behind the pipe flow of groundwater when constructing wells.

Hi Bill,

Nice to hear from you. I agree the silica ash additive was a game changer for concrete, and one of those geotechnical engineering/engineering geology facts that is so fun to share. I wasn’t aware of the application for sealing wells, and wonder if we will be successful in encouraging its consideration when abandoned wells are addressed?