Reclamation’s ambitions writ large – the “Fall-Davis Report”

Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

In complex multi-party negotiations like the Colorado River Compact process, it is rare that major progress or breakthroughs happen during one of general sessions. Instead, real progress is more often made during the more candid discussions between smaller groups of negotiators during breaks, after-dinner discussions, and occasionally sub-committees. Most of these discussions in these venues are not documented in formal minutes.

Thus it is with the development of the Colorado River Compact.

But in the shadows of those committee meetings in the early days of the Compact’s negotiation a century ago, we can see a few key features begin to emerge.

- The idea of apportioning the river’s water based on acreage available for irrigation in each state was central to the leaders’ initial approach to the problem of determining who got how much water.

- In the ambitious projects being contemplated – dams and canals on a scale never before developed in the West – Reclamation was looking for a way to save its floundering fortunes.

While Washington D.C. was being pounded by the Knickerbocker Storm on Friday January 27th and Saturday, January 28th, 1922, the Colorado River Commission met four times, twice each day. The minutes show that the Commission accomplished very little during these meetings. They had “general” discussions and heard from members of Congress, including Senator Key Pitman from Nevada and Representative Phil Swing from California’s Imperial Valley, both of whom would have significant roles in the development of the river. The real action was taking place in the water availability and water requirements committee.

Irrigable Acres?

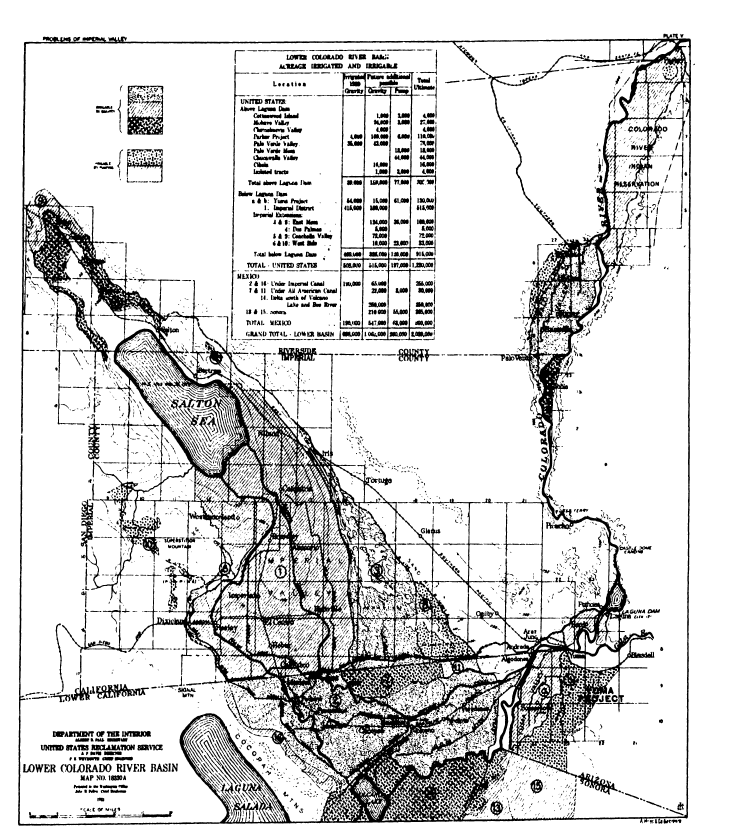

Hoover had directed Arthur Powell Davis to work with both committees. Davis invited the committees to meet at the Interior Department Building where they would have access to the authors and underlying data that went into the “Fall-Davis” report, a comprehensive study of development of the Colorado River Basin prepared by the Reclamation Service at the request of Congress.

Davis and Hoover were hoping the total water requirements for present and future irrigable acreage as identified by the requirements committee would be less than the water available as identified by the availability committee. There would then be a basis for apportioning water use among the seven states. Davis knew that based on the Fall-Davis Report, this result was possible. It all depended on whether the states would accept the data presented in the report.

Rescuing Reclamation’s Floundering Fortunes

Davis was hoping that a Colorado River Compact would lead to the authorization of the Fall-Davis Report’s signature projects, the All-American Canal, and a high dam in Boulder Canyon, which in turn would reenergize his struggling agency. Although the Reclamation Service had already achieved some major engineering feats such as the Roosevelt Dam on Arizona’s Salt River and the Gunnison Tunnel in Western Colorado, the agency had a fundamental problem. It was created by Congress in 1902 to help “reclaim” arid Western lands by providing reliable and affordable irrigation water, but farm economics were not working. Farmers receiving water from Reclamation projects were struggling to repay the federal government for the cost of building the projects.

Davis saw a new opportunity. A 700’ high Boulder Dam would produce a huge amount of hydroelectric power and there was a nearby market for the power, the fast-growing City of Los Angeles and its suburban neighbors. Hydroelectric power generation on Reclamation facilities would be in high demand in the West’s growing urban centers and the revenues it would produce would make projects both economically feasible and politically attractive. But, as Davis and his Reclamation Service colleagues would soon find out, power generation on federally owned facilities would bring in a new set of complications.

In prior appropriation states, power generation was a beneficial use, but not a beneficial consumptive use. One of Carpenter’s major concerns was that the water rights created by these large projects would command most of the flow of the river, interfering with upstream uses for irrigation and domestic purposes. Further, by the early 1920s there was already stiff competition for developing power in the canyons of Western rivers. Just a few months before that January meeting, a private company intent on developing hydroelectric power, Southern California Edison, provided funding for the USGS to install a river gage at a location on the Colorado River most of the compact commissioners had never heard of, Lees Ferry, Arizona.

The goal of committees was to complete their assigned tasks and report back to the full commission on Monday morning, January 30th.

Stay tuned.

Previously: A century ago, Colorado River Compact negotiations begin

I’m enjoying these series of articles. Thanks for them. There is a great backstory to the planning and development of the Lower Colorado River’s infrastructure. However you have to dig deeply for them in old USGS reports and historical collections. Another report that details some of the details of this post is found here: http://www.riversimulator.org/Resources/USBR/ReclamationHistory/KupelDouglasE.pdf