A drying Rio Grande in Albuquerque’s South Valley. July 22, 2022, photo by John Fleck

For the first time in ~40 years (? – see below) New Mexico’s Rio Grande has “broken” – is no longer flowing – in what we call “the Albuquerque reach”.

The river dries not with a bang, but with a muddy whimper and the dawn serenade of awakening birds.

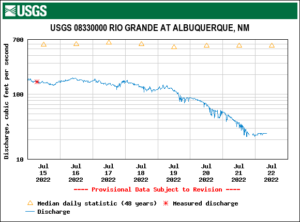

Science watches a river die – the USGS gage on the Rio Grande at Central in Albuquerque

Battered by 100-degree days, with storage above us running out, the river through town has been collapsing all week. When the flow at the Central Avenue Bridge dropped to 50 cfs Wednesday, I made an after-dinner dash to look. After getting word via a friend who had been on a briefing call yesterday that drying was now “imminent”, I got up early, loaded the bike into the Subaru and drove to the South Valley.

Rivers dry from downstream up, and I’d already scouted a path in through the willow thickets behind Harrison Middle School, knowing the drying would start there. Downstream from that point, the Rio Grande gets a break – 75 cfs from Albuquerque’s wastewater treatment plant, a weird way to rejuvenate a dying stream.

My best guess based on the gages is that the “drying” happened some time yesterday. It’s a weird word, because it’s still a lovely puddly mess of mud. But there is no longer water flowing from one puddle to the next. The official word this morning is that there’s a half a mile of drying, which puts the dry stretch starting somewhere around the Rio Bravo bridge (for locals who wanna go see for themselves).

The “bosque”, as we call our riparian forest, is lovely and thick down there, and I had to walk-a-bike quite a few times to push my way through sandy, narrow old foot paths choked with willows to get to the river.

That’s part of what’s weird about this, because what I’m calling “the river” for the purposes of this post is really the surface manifestation of a much more complex hydrologic system, and a big part of the work I’m now doing for the new book bids us to think more broadly about what we mean by “river” here.

The willows and cottonwoods were green and lush. They’ve got roots that easily tap into a shallow aquifer, the “subflow” part of the river. And where the river once spread on its own across a broad flood plain, we now do the job manually with a network of ditches and drains, some of which still had water in them this morning. Along the east side, for example, while the surface manifestation of the Rio Grande itself is now dry, the Albuquerque Drain (really more irrigation main here than “drain”) is flowing today at 120 cfs.

This is a function of our community values. We created an institution a century ago to drain the swampy valley floor and manage a network of irrigation ditches where the river once flowed out on its own (read our new book! as soon as we write it!), and it is functioning as intended.

Even as the river’s surface flows dry, the ditches are drying too. Irrigators have been warned that absent rain, there will be very little to water their land very soon. South Valley horse owners (the biggest consumers of irrigated stuff around here – the horses, I mean) will be buying hay. It’s a very dry year, the agony of climate change dumped atop some water management chaos.

And for the first time in a long time, the river itself here – the part above the ground and between the levees – is going dry.

A note on how long it has been since this has happened here.

The standard line we’ve all been using is that this is “the first time the river has dried in the Albuquerque reach since 1983.”

I’ve heard that said repeatedly by my water manager friends, but I’ve not chased down how we know that.

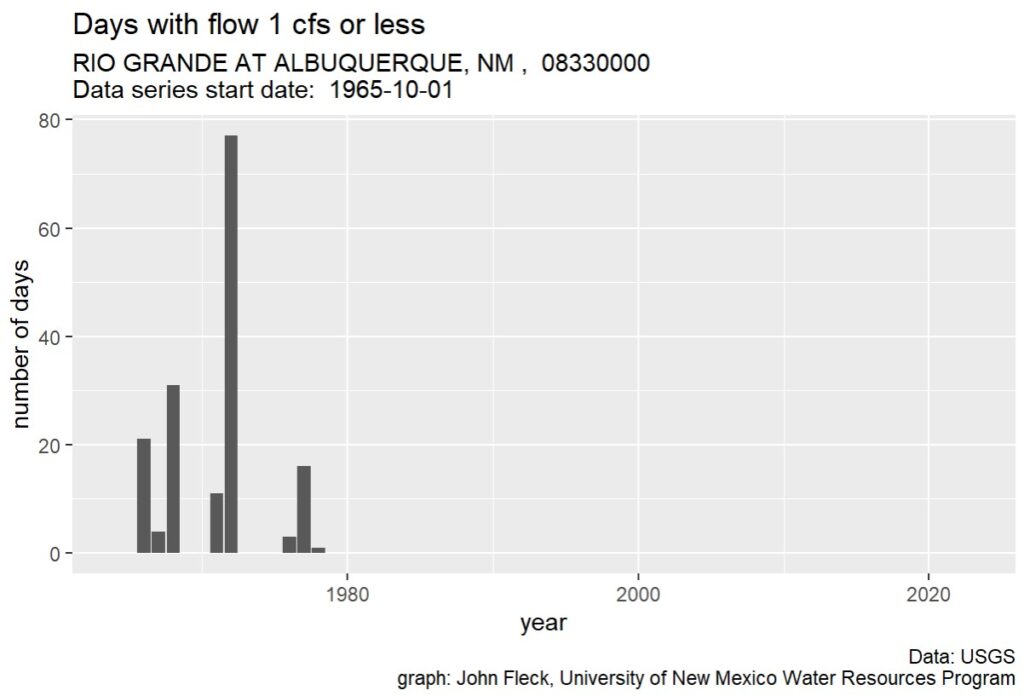

What I do know with certainty is that drying, once far more common in this reach of the river because of the way irrigation was managed in The Old Days (divert the whole river, run the ditches full, irrigate whenever you want) has been rare since the late 1970s.

Here’s a graph of drying days at the Central Avenue gage, where we have records back to the mid-1960s:

Rio Grande drying

Another El Nino year and that is what the Colorado River is going to look like south of the Hoover Dam unless major reductions in diversions happen

I’m a native New Mexican and to see the RioGrande river dried up like that is very devastating…

Alan, I think you meant another “La Nina”.

Not good at all

Pingback: Farmers Look at Rio Grande and See Terrible Sight for First Time in 40 Years – The Right Thinker

Pingback: Farmers Look at Rio Grande and See Terrible Sight for First Time in 40 Years – Indie Media

It’s happened before, it will happen again even after this. No Biggie!

Glad that John is still tracking the water situation so intelligently. I remember back to the early 50’s, before the Cochiti dam was built, and didn’t recall any years when water flowed. Since returning in 2011 I’ve been thrilled to wake up each day and see the flow. It will mean a lot of adjustments to deal with this and other climate-related problems.

Pingback: Drought in the American West, July 26, 2022: Colorado River's upper basin states pledge to cut water use - Circle of Blue

I don’t know who much this applies to this specific subject, but feom reading your other pieces (where the comments are closed) I can’t help to think of the way agriculture uses water in NM along the Rio Grande river. I would say that 90%+ of pecan orchards in Mexico (Chihuahua State) use irrigation for their orchards, and still pecans consume vasts amounts of water, many suggest that is a kind of crop that does not belong in the desert.

Now, in NM, which is supposed to be an advanced society in the largest economy of the world, most pecan orchards still use ancient methods (flooding) of irrigation that waste precious water.

Policymakers should be urged to look into this and do something. Otherwise, this is an all-loose proposition in the medium and long term.