When you hold water behind a flood control dam to protect stuff downstream from flooding, and it inundates a swimming beach, is that a “flood”? Cochiti Dam, May 2023, photo by John Fleck

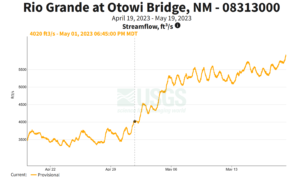

Rio Grande flow dropped this week through Albuquerque, at a time when we should expect it to be rising with the accelerating melt of an unusually large snowmelt.

What’s up with that?

The answer (see below, I’m can’t figure out how to tl;dr this) is a case study in the stuff we’re trying to explain in our new book.

Otowi, Cochiti

Upstream at Otowi, as the Rio Grande enters the last narrow canyon before it hits the Albuquerque reach of the river, what we call the “Middle Rio Grande Valley”, the river is rising.

But between Otowi and us, there’s a big dam at a place called Cochiti.

“Big dam” doesn’t fully capture its bigness. I can still remember the visceral reaction when I was wandering the area around the dam’s eastern flank last year and found a vantage point where I could see the whole thing. The crest of Cochiti Dam is five miles long. It dams not one but two rivers, the Rio Grande and the Rio Santa Fe.

The cultural damage its construction caused to the people of Cochiti Pueblo, the Native American community whose land the dam’s construction slashed through when it was built in the 1960s and ’70s, is incalculably larger.

Here are the words of Cochiti’s Regis Pecos:

To see this construction proceed before our eyes; sacred space and place defined by all those who had gone before violated before our eyes was very hurtful. Unimaginable pain. It was piercing the hearts of our people daily. One of the most emotional periods in our history was watching our ancestors torn from their resting places, removed during excavation. The places of worship were dynamited, destroyed, and desecrated by the construction. The traditional homelands were destroyed. When the flood gates closed and waters filled Cochiti Lake, to see the devastation to all of the agricultural land upon which we had walked and had learned the lessons of life from our grandfathers destroyed before our yes was like the world was coming to an end.

A brief history of the idea of a dam at Cochiti

For the new book (Fleck and Berrens, Ribbons of Green: The Rio Grande and the Making of a Modern American City, to be published by the University of New Mexico Press once Bob and I figure out how to write it), I’ve been working on a chapter about … well, I’m not sure exactly what it’s about yet, which is why I’m working here in the sketchbook.

The first mention of a dam in White Rock Canyon seems to have come from John Wesley Powell in an 1890 report to Congress. The arrival of the railroad in central New Mexico had happened 10 years before, and Albuquerque was beginning to claw its way into modernity when Powell said this:

The canyon walls are hundreds of feet, and in some cases more than a thousand feet, above the waters. White Rock Canyon empties below into a valley which I shall call the Albuquerque Valley. In it lie Bernalillo, Albuquerque, Los Lunas, Socorro, and other towns. Now, all the water that comes out of White Rock Canyon can be used in the Albuquerque Valley. Whoever has control of that point owns that dam site and has the right to take the water out of its natural channel and carry it into canals – has command of all the agriculture of that great district.

“Whoever has control of that point” – that phrase jumped at me off the page, angrily demanding to be admitted to the pages of our book. “Whoever has control of that point….” Because from time immemorial, that point has been a part of Cochiti.

By the 1930s, “Whoever has control of that point….” was the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, which built a low irrigation diversion dam – it didn’t impound water or slow flood waters, just created a stable surface for an irrigation head gate.

By the 1960s, “Whoever has control of that point….” was passed to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which built the huge dam that looms over Cochiti Pueblo today.

The notion of “flood control”

I’m rolling all of this around because of two things. The first is some remarkable Congressional testimony from Jose Alcario Montoya, Cochiti’s governor, to members of Congress in 1943 when they were considering construction of a flood control dam to protect Albuquerque. Here’s how I’m excerpting it for the book:

“And so I have heard yesterday here that we are in very great danger from flood and that we are losing land,” said Montoya, whose community sits at the valley’s upstream end 75 miles above Albuquerque. “I do not think it is so that we have lost any land.”

“Suppose the land is on one side of the river and the river cuts over and cuts part of that land away. While it is doing that it is making new land on the other side and so we never lose any. When the river gets down, we use that land again for cultivation.”

The second was a conversation with the person working the entrance booth at Cochiti Lake.

Pooled behind the dam, a modest “recreation pool” allows swimming and no-wake boating. But the booth person explained when I visited that the swimming beach was closed “because of the flood”.

This use of the word was weird.

The reason Cochiti Lake is rising, and the flows downstream of the dam have been reduced, is a decision by water managers to throttle back flows to protect a bridge culvert downstream, in Los Lunas, New Mexico. Last Saturday night, the culvert collapse and swallowed up a bicyclist. (He’s beat up, but OK.)

The Oxford English Dictionary’s fourth definition for flood kinda matches the sense being used for the closure of the Cochiti swimming beach: “An overflowing or irruption of a great body of water over land not usually submerged.”

The point Montoya was making was that if you let a river move around, and then move with it, “flooding” is not a thing that happens. But as soon as we built a city in the place where a river would naturally go during high spring flows, you create “flooding” where in the past it would simply have been a river doing its normal river things.

So you build bridges, and culverts, and a big dam upstream to contain “floods”. Instead of a river’s natural bed, we name it the “flood plain”, which naturally spilled out of my keyboard a few paragraphs ago without me even realizing the semiotic baggage the phrase carried. (See scare quotes.)

And you build a flood control dam. And then you build a swimming beach, and then when the water behind the flood control dam starts to rise because you are trying to protect a bridge culvert in Los Lunas, and inundates the beach, you call that a “flood”.

Sorry this was so long, I didn’t have time to write a shorter blog post. I’ll tighten it up for the book.

John

The Crest of Cochiti is not 5 miles long. I have just measured it off of Google Earth. It is about 2.45 miles long

Check it on the USBR web site.

Bill.

Timely, I was at the dam last week and stopped my vehicle in the middle of the road astounded by the enormity of the dam that stretches five miles. So out of place in a land that should have its own free flowing water, that doesn’t “flood” but replenishes and grows and fortifies. But alas, the beach is closed because getting to the man-man comforts requires first getting wet feet.

I love this post. The words “point of view” come to mind. Powell, Pecos, Montoya, USBR, Fleck, Los Lunas, your Readers. What do we see, or feel, when we look at a landscape?

So, he take away is that man has caused the floods by his very presence and invasion of the flood plain, which I agree with. A lesson I learned from the residents of oases in Mauritania is that they never build in the oasis but on the dry periphery of the oasis. Take a look at it on Google Earth by searching for Toungad, Mauritania. I have been there and believe me it is gorgeous.