High December flows on the Rio Grande in New Mexico’s middle valley, an artefact of river management rules. John Fleck.

This was a big flow year on New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande, but weird, in ways that highlight the challenges we face.

Flow in the River

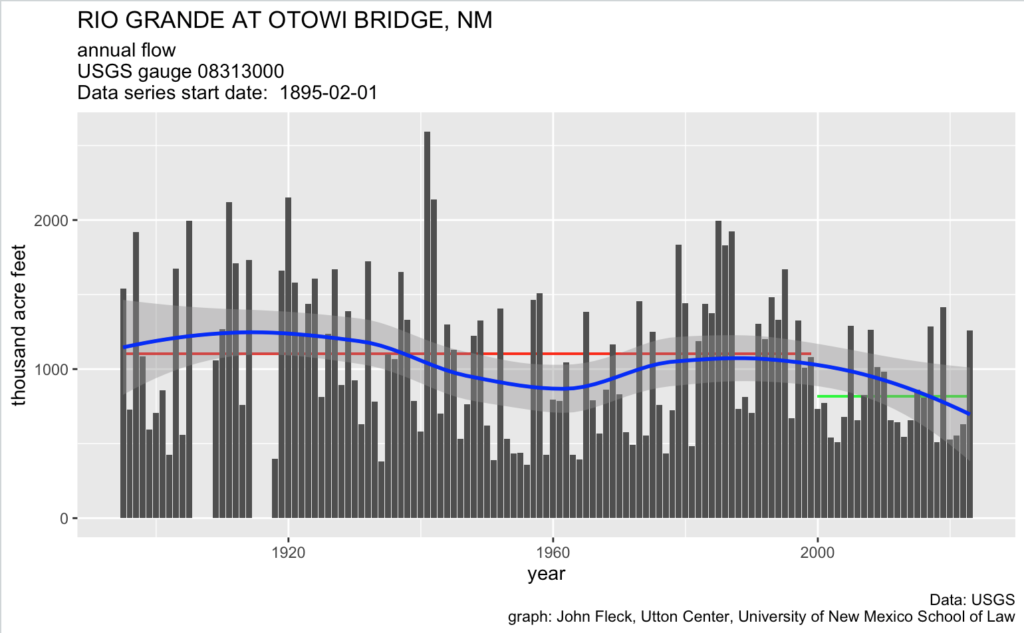

Total flow into New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande Valley (measured at Otowi) sits at 1.26 million acre feet with two more days’ flow to go, so round it off to 1.3maf.

So a big year! Yay! Look at all that water in the picture above, a bank-full Rio Grande flowing past Rio Rancho, New Mexico, in December. And yet there I was in August watching dogs gamboling on the sand bed of a nearly dry Rio Grande. What’s up with that?

The answer involves the interaction between a climate change-driven megadrought, the use of the river by human communities, and the tangle of rules that govern management of the 21st century Rio Grande.

The short term tangle involves El Vado Dam, currently being renovated and therefore unusable for storage. That meant that by August the declining inflow of late summer with a lousy monsoon left the river nearly dry, regardless of the winter snowpack.

This problem, which will go on for several more years, means that irrigators will depend on run-of-the-river operations for late summer irrigation for a while yet. Given that irrigation water also supports environmental flows on its way to the irrigation diversions, this is also bad for things like the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow and the river flowing through my city.

The longer term tangle involves competing community values among the various ways we use water, combined with a lack of tools to reduce that use.

Because, with climate change there is less water.

Inkstain is reader supported

Inkstain has been a Nazi-free zone for more than 20 years, mostly because it’s just my blog and I’m not a Nazi. (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, bless you. Google “Substack” and “Nazis”, it’s the latest digerati kerfuffle.)

But, like all your favorite Substackers, it is reader supported! Thanks as always to our readers. (And if you don’t know what Substackers are, again, bless you.)

The Tangle: Moving Water in Time

First let’s pin some data to our bulletin board:

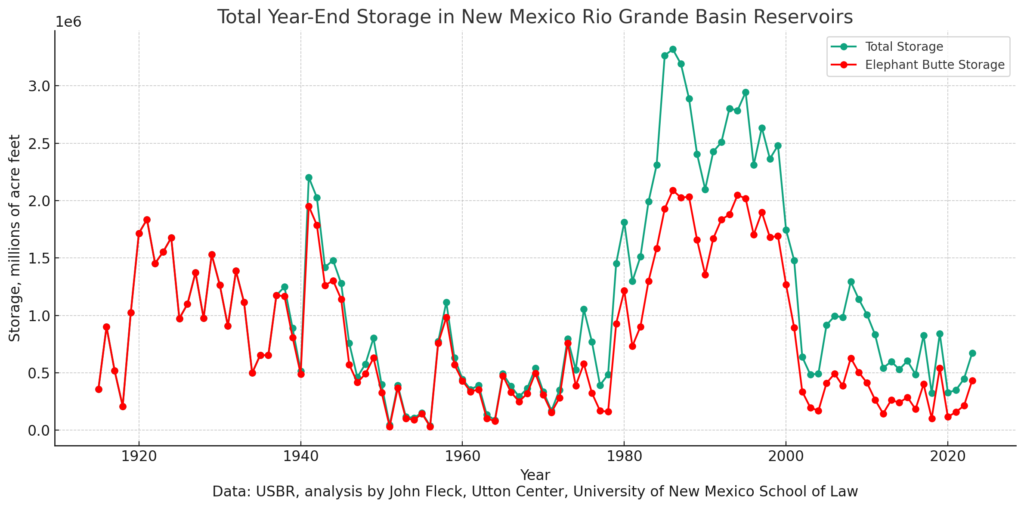

There’s an old water management adage: Canals move water in space, reservoirs move water in time. We built them to store water in wet years, effectively moving it in time to dry years. So how much did we so move this year?

Inspired by Jack Schmidt’s monthly Colorado River posts, I spent my Saturday coffee wakeup this morning totaling up sorta year-end storage in the reservoirs I care about (from top to bottom Heron, El Vado, Abiquiu, Cochiti, Elephant Butte, and Caballo). It took longer than I expected because I was so distracted by all the amazing history embedded in this graph. 1986-87, yowza, what’s up with that?

Flow this year was ~440k acre feet above the 21st century average. Total end of year storage is up ~220k acre feet. There’s so much mixing of apples, oranges, durian, and pawpaw here that it’s not a straight up comparison, but it should give you a feel for the challenge: we only saved a part of the bonus water. We used a lot of it.

The Management Levers

Let’s imagine for a moment that we wanted to pull some water management levers to change that balance by reducing consumptive use (by “use” I mean evapotransporation, human and non-human) in the Middle Rio Grande Valley. We’ve basically got four different categories of use:

- The cities, especially Albuquerque

- The Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, which manages irrigation water for some commercial farms and a lot of custom and culture/lifestyle stuff

- Domestic wells

- The river – evaporation and riparian consumption by our beloved bosque

Let’s take these in order of smallest to largest water use.

The Cities

We’ve already cranked down pretty hard on this lever. With a combination of water use reductions and a shift from groundwater pumping to imported Colorado River water, we’ve already cranked down extremely hard on this lever. This is the one area of the system that is already aggressively regulated.

If you want to crank down harder on this lever, the two points of entry in the legal/political/policy system are the Office of State Engineer/Interstate Stream Commission, which do the regulating, and the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority Board, which is made up of elected city councilors and county commissioners.

The District

Consumptive use by the Conservancy District’s irrigators is several times larger than the cities. The District took voluntary action this year to reduce use, delaying the start of irrigation season and cutting diversions once they started by 20 percent to try to get more water to Elephant Butte Reservoir.

With federal money, the District paid folks irrigating a relatively small portion of the valley’s acreage to fallow this year, and the acreage is going up in 2024. But the numbers remain small relative to the size of the problem.

If you want to crank down harder on this lever, it’s not clear to me what the state’s legal authority might be. There may be some, but it’s not been tested. But the District is governed by an elected board. That’s a lever, though it’s worth pointing out that the board got a lot of crap this year from irrigators about they steps they did take. Incentives in all of this are weird, it’s tricky to figure out how to work this lever.

Domestic Wells

We don’t regulate these at all. We have no idea how much water they use, but it sure looks to use like there’s a lot. We don’t really even know how many there are, there seem to be a lot drilled illegally. (If you’re a UNM Water Resources Student, hit me up on this! We have some ideas for a really impactful masters degree research project.) We probably need to think about building a lever here, but we currently don’t have one. The state legislature might be a place to start? Maybe some un-exercised legal authority at the Office of State Engineer? (See NMAC 19.27.5.14, my day job, such as it is, is at a law school, though IANAL it sure looks like that could only apply to new wells, so horse out of barn etc.)

The Bosque

The biggest water user, likely larger than irrigation, is the riparian corridor itself. It’s largely unnatural, vegetation exploiting a niche created when we built levees and constrained the river’s flow, but whatever. It feels like “nature”, and we love it. And even if we didn’t it’s not clear what a lever to reduce that use might look like.

Values

Each one of these uses is valued by some segment of our community, and we seem to lack the tools to reconcile these competing values, which is why I’m pretty excited about the 2023 Water Security Planning Act.

A note on sources and methods

The reservoir data is from the USBR’s reservoir data archive. The latest 2023 data is from Dec. 18, so I matched up this year’s with Dec. 18 in previous years. My quick sensitivity check led me to conclude “Meh, good enough for a blog post.” For the early years, the USBR just reports a single year-end number for El Vado. My quick sensitivity check led me to conclude “Meh, good enough for a blog post.”

Flow data is from the USGS Otowi gage.

It is, in fact, spelled “gage“, just ask Bob, he’ll tell you.

I currently have 26 browser tabs open, including one with an amazing list of obscure fruit, did you know that Mark Twain called cherimoya “the most delicious fruit known to men.”? I had a bunch more I wanted to say, but that’s enough, it’s time to hit “publish”. Thanks for reading.

John:

You are dissimulating. Why not discuss the really big gorilla in the room. Evaporation from all of the artificial reservoirs on the Rio Grande upstream of Elephant Butte which is charged against the Middle Rio Grande Basin since 1948 when the measurement gage was moved to the gaging station immediately downstream of the dam. Add-in Caballo too. We modelled this evaporation in 1979 and presented it in courtroom testimony against the State and Feds and the court bought our arguments and found the reservoir loss so egregious that the Jicarillas prevailed in the suit. It turned out the loss was greater than we calculated because of high rainfall in the 1990’s all of the SJC water stored there by Albuquerque spilled three time.

Thanks I belong to the Tularosa Ditch Corporation and live in the 49 Blocks area of the Acequia. The farmers are wanting more water and it’s so hot that I think it evaporates at a high rate. Should we be farming in the desert? They have to use wells anyway.