NEAR THE CONFLUENCE OF THE RIO PUERCO AND THE RIO GRANDE – The broad delta where the Rio Puerco meets the Rio Grande in central New Mexico has never been a great place to live, though people try. To the east, across the river, the Ancestral Puebloan Piro built the village Spanish colonizers named “Sevilleta” (“little Seville”) on a Pleistocene gravel bench up out of the flood plain. Because when the Rio Puerco is in flood, it really is in flood.

In their 1984 book Rio Abajo: A Prehistory of a Rio Grande Province, Michael Marshall, Henry Walt, and colleagues chose a naming convention that I like, even though it is confusing as hell. The traditional naming convention for the Rio Grande in Spanish New Mexico is to divide the river and its human communities (as always, the physical geography creates the structure the human communities follow, but it’s the human communities driving the naming) thus:

- Rio Arriba for the landscape north of the great escarpment known as La Bajada.

- Rio Abajo for the landscape south of La Bajada

But both physical and human geography suggest a second division. It is worth quoting their reasoning in full (Marshall and Walt 1984, p. 1):

The term “Rio Abajo,” as it is used in this volume, is of Pre-Revolt vintage and applies specifically to the Pueblo and Hispanic province of the Piro, believed to have extended from the Paraje de Fra Cristóbal on the south to Abeytas or Sabinal on the north (Figure 1.1). In 1776, nearly a century after the demise of Piro-Hispanic civilization in the Socorro region and just before the resettlement, Fray Francisco Antanasio Domínguez divided the Kingdom of New Mexico into two sections: Rio Arriba and Rio Abajo (Adams and Chávez 1956:7). At that time, Rio Abajo was described as the area from Cochiti Pueblo on the north to below Isleta Pueblo (i.e., Sabinal) on the south. Since the emphasis of this study is on the Piro and the Pre-Revolt era, we have employed the archaic usage of the term “Rio Abajo” from the time when Colonial Hispanic settlements extended as far south as Senecú. From a research perspective it is logical to describe the region north of the Piro district and south of La Bajada as “Rio Medio,” although this term is not found in the historic archives.

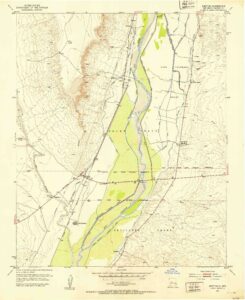

Spatting with its much larger sibling, the Puerco at the confluence, with its ephemeral flows but massive sediment load when it does run, has shoved the Rio Grande to the east in a broad bend that snaps nicely into view in the 1952 USGS topo map to the right. Blasting out into the valley floor, the Puerco’s delta has created a broad, gentle high spot, and in flood water backs up the valley to the north. I have seen this.

It is sediment that drives the story my collaborator Bob Berrens and I are trying to understand for the new book project we’re beginning to explore. Managing the sediment in this stretch of the river – from the Puerco and the Rio Salado eight miles downstream, plus umpty named and unnamed arroyos that blast in under the weight of summer rains – is the central challenge for water management in this stretch of the Rio Grande in the 21st century.

We drew our boundaries around the stretch of river from the Puerco down past San Marcial for different reasons than Marshall and Walt. Ours was based on river management, theirs was cultural. In the Marshall-Walt topography, Rio Abajo is the home of a people we’ve come to call the Piro, a name applied by the Spanish to the Ancestral Puebloans who lived along this stretch of the river before Spanish colonizers arrived in the 1500s (Bletzer 2013). But old human settlement patterns and modern river management challenges are built atop the same foundation.

I’m nervous about pushing too hard on the idea that geomorphology drives the structure of human communities on the landscape. Lots of other stuff is involved, but geomorphology lies at the base of the rest of it, our decisions about where to live, to hunt and gather, to build our farms and cities. Why did the Piro build on the east side of the river here? How did they use the river, live with the river? Today, the question about where we build our highways, our railroads, and our levees and ditches, are motivated by the same things. So I put the bike in the car yesterday morning and drove down to La Joya, the state game park on the river’s west side just downstream from the confluence, to try to understand the shape of the landscape.

This has become a central piece of my practice as a writer in the last few years. I’ve always pursued what I have called “journalism by wandering around,” going to a place and just kinda being there, looking around with curiosity, thinking about how and why stuff spatially fits together. The networked nature of water lends itself to this style of thinking, because water moves in paths, and the humans moving with it follow and, increasingly, shape those paths. In the last five years, as my work has become more intimately place based, I’ve done it on my bicycle. I move at the right pace to feel the landscape.

I parked at one of the “La Joya Wildlife Management Area” pullouts near the river and headed north, up the east side service road (the side closest to the river) for the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District’s Unit 7 Drain, a bizarre water management channel that does what it says on the tin. I need to do a full post on the Unit 7 Drain, it’s super weird. It snakes through the Lomas Pardas Narrows downstream of the Puerco, siphons under the Rio Salado and into the Angostura de San Acacia, winding parallel to railroad tracks on the west and the Rio Grand’s main channel on the east, slicing through a wildlife refuge and hunting park, turning drain water into a fresh source of irrigation supply for Socorro County farmers. It’s one of my favorite spots on the river and is for sure one of the weirdest MRGCD ditches, right up there with the place in the South Valley where the Barr Canal cuts through a junkyard. There is, or was, a much beloved Albuquerque post-punk band named after the Unit 7 Drain. You can’t make up shit that good.

Picking which side of a ditch to ride on is always tricky, because I want the side that’s most rideable, meaning least sandy. But I also want to be on the side closest to my ultimate destination, because often there aren’t any crossings, and wading through a ditch with my bike is impractical. The road yesterday was good, the sand mostly packed down by recent summer rains, which also made it green. The white-crowned sparrows seemed happy with the results, if not annoyed at my presence, doing that thing they do where the clustered in groups around the ditchbank vegetation and dashed out ahead of the bike, as if they were escorting me.

I was deterred from reaching my goal – the actual confluence of the Rio Puerco and the Rio Grande – by a gate and a no trespassing sign on the service road. I was pretty sure this was the classic western move of putting up “no trespassing” signs to privatize a public space, but I was having a leisurely morning and didn’t fancy a confrontation with the sort of entitled people with guns who frequent “hunt clubs” and exploit murky areas of law to claim ownership of rivers, so I turned back.

A look at county and MRGCD property maps when I got home supported my hypothesis – the actual private property involved is a third of a mile away, and the service road itself sure looks to me like MRGCD property the whole way – in other words, public property – both sides. But MRGCD access rules are complicated, and a careful post-ride study of the satellite imagery now that I have a better feel for the place suggests several routes to the confluence that should avoid any entanglements with the gray areas of rivers and property law (see Adobe Whitewater decision – the hunt club people do seem to actually own a big piece of the Rio Puerco itself). So I’ll be back.

References:

- Adobe Whitewater v. NM State Game Commission, 519 P. 3d 46, 2022 NMSC 20 – NM: Supreme Court, 2022

- Bletzer, Michael. “The First Province of that Kingdom: Notes on the Colonial History of the Piro Area.” New Mexico Historical Review 88, no. 4 (2013): 4.

- Marshall, Michael P., and Henry J. Walt. Rio Abajo: prehistory and history of a Rio Grande province. Museum of New Mexico Press, 1984.

I’m a big believer in “sense of place” journalism, and your approach is perfect for this. Understanding how the land rises and falls is a snap on two wheels.

Also appreciate the historical background here… it had not dawned on me that NM was part of a different country for a long time.