Rio Grande, San Luis Valley, southern Colorado

Rio Grande, San Luis Valley, southern Colorado

tl;dr The Phoenix kerfuffle over a Nestlé bottled water plant is an example of people distracted by a facile but meaningless caricature of the problem they think they care about.

longer: When University of New Mexico Water Resources Program graduate student Sara Gerlitz* was looking at Arizona water management over the last year, she zeroed in pretty quickly on the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District’s “2015 Plan of Operation“. If you’re interested in the long term sustainability of the greater Phoenix area’s water supplies, the plan and the processes it describes are super important.

The plan lays out how central Arizona water managers will meet their legal obligations to provide a 100-year assured supply of water to growing parts of Central Arizona in the context of groundwater pumping regulations and available supplies of imported Colorado River water. This is big deal stuff, central to Arizona’s sustainability. The back-and-forth over the details – the reasonableness of the assumptions that went into it, the risks if the estimates are wrong – makes for important reading if you’re interested in the deep and important details of how Arizona plans for its water future. But to the people of greater Phoenix, this seems to have not been a very interesting process at all. When the Arizona Department of Water Resources held a legally required public hearing on the plan March 30, 2015, not a single member of the public showed up to testify. Zero.

Irrigated alfalfa on the east side of the Phoenix metro area, February 2015

It is interesting to compare that lack of public attention with the current public kerfuffle over Nestlé’s plans to build a new water bottling plant in Phoenix. Some perspective: the CAGRD’s new plan of operation contemplates the need for roughly 50,000 acre feet of water per year by the mid-2030s. In comparison, the Nestlé plant will use about 100 acre feet of water per year. The CAGRD process was making important policy decisions about a supply of water 500 times larger than the Nestlé plant. No members of the general public showed up to the CAGRD process, while 37,000 people by Friday had signed an on line petition against the Nestlé plant.

Back in my errant youth, when I worked as a volunteer documentation writer for the big free software GNOME project, I became intimately familiar with what we called “bicycle shed” discussions, a shorthand drawn from the work of 1950s management scholar C. Northcote Parkinson. Here’s a nice short explanation:

Parkinson shows how you can go in to the board of directors and get approval for building a multi-million or even billion dollar atomic power plant, but if you want to build a bike shed you will be tangled up in endless discussions.

Parkinson explains that this is because an atomic plant is so vast, so expensive and so complicated that people cannot grasp it, and rather than try, they fall back on the assumption that somebody else checked all the details before it got this far….

A bike shed on the other hand. Anyone can build one of those over a weekend, and still have time to watch the game on TV. So no matter how well prepared, no matter how reasonable you are with your proposal, somebody will seize the chance to show that he is doing his job, that he is paying attention, that he is *here*.

Sometimes also called “Parkinson’s law of triviality“, it’s popular among geeks and mostly applied to software development discussions. But it generalizes, a nice shorthand for why people attach to simple things they think they can understand and act on, while ignoring the more important but vast and complex. I get why bicycle shed discussions are inevitable. But that doesn’t mean they are not a problem.

Here’s why, in the case of Phoenix and Nestlé.

Those 37,000 petition signatures suggest a bunch of people who care a lot about the sustainability of Phoenix’s water supply. That’s great! But they’ve attached that wagon of caring to the wrong horse. Central Arizona can do a great job of managing the sort of long term water sustainability problems sketched out in the CAGRD process (and in a bunch of others policy processes now underway), and it will have plenty of water for a Nestlé plant and lots of other things future Phoenicians (?) might want to do.

Or it could do a terrible job at those big picture processes, in which case rejecting the Nestlé plant won’t matter a hill of beans.

But a whole bunch of people have been left with an entirely different perception – that caring for Phoenix’s water sustainability future means killing that Nestlé plant.

This is a big problem for the pursuit of water sustainability in Phoenix, because the current community water management has done some important things to move it down the path toward sustainability (water use declining, aquifer rising, innovative conjunctive groundwater management institutional arrangements, etc.). If the protesters don’t get their way on the Nestlé plant, they’re gonna think Phoenix doesn’t care about water supply sustainability. And that would be completely wrong, and Phoenix water management would lose an important set of allies in the hard work yet to come in ensuring the sustainability of its water supply.

I don’t blame the mass of people signing the Nestlé petition here. Bicycle shed problems are inevitable because people care. Something must be done. This is something. Therefore, this must be done. The important thing is for the leadership of the anti-Nestlé crowd to demonstrate some seriousness about Arizona’s real water supply sustainability challenges, leading this mass of people now assembled into a more meaningful discussion of water supply sustainability, and not waste all of our time arguing over a bottled water plant.

* CAGRD governance issues were just a piece of Sara’s masters degree project, which primarily focused on the use of remote sensing tools to help water managers get a handle on agricultural water use – something that will be critical for Arizona’s long term water supply sustainability. It was a great project – she just finished, it’s not on line yet, but will soon be posted here.

I got an education this year in the nuances of global toxic materials regulatory regimes when I served on UNM graduate student Rachel Moore’s masters committee with Caroline Scruggs, a professor here at the university who’s worked for years in this area. (The paper on their work is here.)

Caroline showed up in the Albuquerque Journal yesterday, talking about the regulatory reform effort being led by Sen. Tom Udall, D-N.M.:

Caroline Scruggs, an assistant professor at University of New Mexico who studied the safe use of chemicals while earning her doctorate from Stanford University, said her research has shown “a clear and urgent need” to update the 1976 law but that becoming a mother drove the point home. She said she has tried to study the chemicals in products her sons use and worries about exposing them to toxins.

“Americans shouldn’t need to research product ingredients or have training in toxicology or chemical engineering to understand if they’re buying safe products,” she said. “Tens of thousands of chemicals are on the market and only a handful have received safety testing and under current (federal law), and it’s almost impossible for EPA to restrict risky chemicals.”

In addition to toxics regulation, Caroline’s doing a lot of work on technical, economic, and social issues around direct potable reuse of municipal wastewater, and is very active working with students in the UNM Water Resources Program, where my little academic beachhead is housed. (Wave to future students!) One of the things we talk about a lot is the translational component of academic work – how to get it out of the academy and into the political and policy arenas. Great to see Caroline doing that here.

Laura Paskus did a lovely job chronicling my post-newspaper-journalism (post-journalism?) life and thinking about water and the news, no longer the old nickname – “the harbinger of doom”:

“I began to realize there was this other story about people not running out of water,” he says.

Locally, for example, he points to a drop in Albuquerque’s water consumption. At the same time, as the city relied less on groundwater pumping and more on water from the Rio Grande, the aquifer started recovering.

“By the end, I was chafing under the constraint of what a newspaper story should be – 600, or maybe 750 words,” he says. Short, to-the-point, and focused on a crisis. In general, newspapers aren’t in the business of peddling stories about complicated issues and the subtle, nuanced solutions people devise.

Despite the nickname, Fleck just isn’t a gloomy guy. The grind of it all began to wear on him.

Brent Gardner-Smith shares news of an effort around Carbondale, Colo., to leave more water in the Crystal River in times of drought:

CARBONDALE — In an effort to leave more water in the lower Crystal River in dry years, a growing number of irrigators in the watershed are considering entering into non-diversion agreements and are reviewing ways to deliver water to their crops more efficiently.

The agreements would be a product of discussions surrounding the recently released Crystal River Management Plan, which sets a goal of adding 10 to 25 cubic feet per second of water into the river during moderate and severe drought years.

The additional water could come from paying irrigators to reduce their diversions by 5 to 18 percent, depending on conditions, and by helping irrigators improve irrigation ditches and installing sprinkler systems.

This is made possible to 2013 Colorado state legislation that creates a legal framework under which farmers could reduce water use in situations like this without jeopardizing their underlying water rights, creating a path around the thorny “use it or lose it” problem. (Background on the law from a University of Denver Water Law Review summary of the legislation here.)

A big thanks to J.R. Logan for this piece,which talks about the New Mexico acequia water governance model as an alternative to the “water’s for fighting over” narrative:

Ledoux says sharing water has always been customary. Taking more than your fair share would have simply been wrong. This notion of sharing is not intrinsic to water law in the American West. In fact, it’s just the opposite. But some believe the collaborative approach modeled by the acequias is a more logical and sustainable way to administer water in an increasingly challenging environment.

The “some” in that “some believe” includes me (shout out to J.R. for including my thoughts in the piece):

Fleck says these partnerships go largely unnoticed because they’ve managed to avoid the conflict narrative that dominates discussions in the region. By approaching the issue more optimistically, Fleck hopes to build momentum for new, more creative collaborations. “It’s really important that we nurture those and pursue them,” Fleck says, noting that climate change and continued population growth will likely make water management in the Southwest more challenging.

I wrote a book about that. Available for pre-order now.

Striking the right tone in my about-to-appear-on-the-shelves book on Colorado River water management was tricky. The problems are serious, but I am optimistic about our ability to solve them, and in the book I try to lay out both the nature of the problems but also what the solutions can and do look like. It’s not hard to find doom out there, it’s in the description of the solution space that I think I have some contribution to make. So I’m pleased with the final cover design the team at Island Press has come up with:

Water is for Fighting Over

The old cover (you can still see it on Amazon – pre-order now! – the new one hasn’t migrated upstream to retailers yet) looked a lot more doomy – this strikes a more hopeful tone.

Via High Country News, Paige Blankenbuehler revisits the San Luis Valley in southern Colorado, to see how an innovative collective effort to reduce pressure on an agricultural aquifer is faring:

Today, four years into the operation of the project after it launched in 2012, the aquifer is rebounding. Water users in sub-district 1 have pumped one-third less water, down to about 200,000 acre feet last year compared to more than 320,000 before the project. Area farmers have fallowed 10,000 acres that once hosted thirsty alfalfa or potato crops. Since a low point in 2013, the aquifer has recovered nearly 250,000 acre-feet of water. By 2021, the sub-district project plans to fallow a total of 40,000 acres, unless the ultimate goal of rebounding the aquifer can be reached through other conservation efforts, like improving soil quality and rotating to more efficient crops.

The plan’s proponents say it provides a template for groundwater management in other arid communities whose agricultural economies are imperiled by drought. “The residents of the valley know that they are in this together, and that the valley has overgrown the water available to us,” says Craig Cotten, Almosa-based division engineer for the Colorado Division of Water Resources. “This is a water user-led solution, which makes it unique. I really think this can be a model.”

Blankenbuehler’s story is part of the Small Towns, Big Change project, a collaboration of between the Solutions Journalism Network and a group of innovative local and regional media outlets.

We’ve had a healthy freakout over the last couple of weeks about the fact that Lake Mead, the nation’s largest and iconic water supply reservoir, is (again) at its lowest point in history (meaning the lowest since they built it in the 1930s). Brad Plumer has a good summary of what’s what. It’s an important symbolic milestone, suggesting that we’re heading into unsustainable water use territory by taking more water from the system each year than is returned by rain and snow upstream.

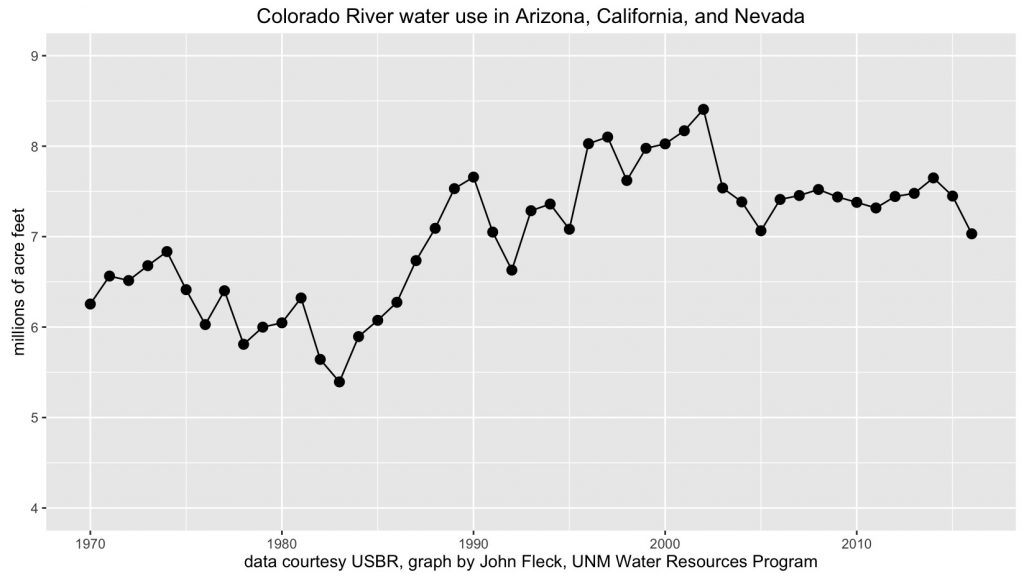

But in the midst of the freakout, there’s an important point that’s worth attention. The latest forecast for 2016 shows Colorado River water use in Nevada, Arizona, and California on track to be the lowest since the early 1990s. (I’ve plotted this back to 1970 because that’s a good starting point for the “modern era” of Colorado River water management.)

Colorado River water use

Under the current Law of the River framework, the three Lower Basin states are in theory entitled to 7.5 million acre feet of water. They’re only forecast to take 7.031 maf (data pdf here). What’s going on? A series of voluntary agreements aimed at slowing the decline of Lake Mead – an actual reckoning in on-the-ground water management of the reality that there is not enough water in the system for business as usual. Arizona, with the greatest risk because of its large take on the river and junior priority, is forecast to take 93 percent of its 2.8 maf allotment. California is taking 94 percent of its 4.4 maf allotment, and Nevada is forecast to take just 87 percent.

These cuts are not enough. Lake Mead is still forecast to drop another 2 feet in 2016. But the conservation measures being implemented in the Lower Basin states are unquestionably slowing Mead’s decline, demonstrating the institutional learning necessary for the Colorado River-dependent states to figure out how to survive on less water, and most importantly demonstrating that there can be a way to avoid the “tragedy of the commons” conflict path.

The Rio Grande through Albuquerque has been rising for the last week or so, and is now about to make a good-sized jump in flow as water managers push some extra flows from storage behind upstream dams to encourage our beleaguered silvery minnow to spawn. From a notice sent out this afternoon by Mary Carlson at the Bureau of Reclamation:

The release from El Vado to Abiquiu is currently at 2,000 cubic feet per second. That will double by Wednesday and then will begin dropping back down to about 2,000 cubic feet per second by Friday. It will remain at that level for a couple of weeks. This flow, which is beneficial to the ecosystem of the Rio Chama, includes the bypass of the inflow to El Vado Reservoir as well as the scheduled release of water stored with approval of the Rio Grande Compact states of Colorado, New Mexico and Texas. This agreement allowed for the storage of close to 40,000 acre-feet of water in El Vado between May 2 and May 20….

The release from Abiquiu Reservoir is scheduled to rise to about 1,800 cubic feet per second by Wednesday and continue for approximately two weeks. The release from Cochiti Dam will be close to 3,300 for about two weeks. This flow will also benefit the entire ecosystem and is aimed at signaling the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow to spawn. Minnow numbers have been low in recent years as the drought has continued. However, a better spring runoff last year helped support a slight improvement in minnow abundance. Monitoring for silvery minnow eggs will be conducted throughout this operation.