I’ve begun putting scare quotes around “done”, but we just passed a major milestone deserving of the word – done – with my upcoming book on the problems facing the Colorado River Basin and what I think solutions might look like. The book is now fully edited and entering the production process at Island Press. And when I say “fully edited” I have to add the scare quotes too, there are a couple of more rounds of copy editing and proofreading as part of said production process. But It’s now largely off my desk and into the hands of the professionals.

Lake Mead at sunset, by John Fleck

If I was a better writer I’d have a good metaphor here for the strange time-shifting experience of writing a book. Maybe a life that spans global time zones – I’m over here on one side of the International Date Line done with it, and y’all are off there on the other side waiting until next fall to read it? (You are anxiously awaiting the chance to read it and buy copies for all your family and friends, right? Put it on the holiday shopping list now.) Maybe the metaphor is the old days when news had to travel by boat around the Horn?

It’s a weird limbo, starting to work on other projects (I’ve already written some other stuff, teaching is the most fun right now), starting to think about what a next book might look like, while the thing that sorta feels behind me (The Book) is still very much ahead of me.

The last task was the acknowledgments, and it was the hardest, because so many people helped me. But I realized in sorting through the lists of the many people who gave their time and data and insights that they shared a common characteristic – a clear-eyed view of the difficulty of the Colorado River’s problems, combined with a persistent optimism that they can be solved.

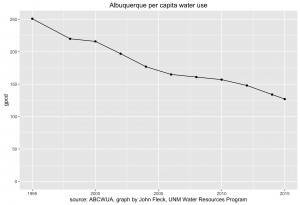

I hope the book honors that zeitgeist, which I share – that the inexorable draining of Lake Mead demonstrates a clear problem in our relationship with water in the Colorado River Basin (we use too much of it!) but the litany of success stories I chronicle suggests significant progress, both in water conservation on the user end, and in institutional frameworks needed to manage the allocation of an increasingly scarce resource.

I’m off to Las Vegas this week for the annual CLE Law of the Colorado River conference. It’s a gathering of the community, and I’m looking forward to hearing the latest and sharing some of my ideas about where we go from here.

I’m driving over a day early, to spend time wandering around looking at water. It’s always been one of my great joys, getting down to the water, seeing how it moves through the system, and I’ve been in the writing tunnel and away from the water too much over the last six months. There’s a big reservoir out east of Vegas that I’ve grown fond of over the last few years, gonna pay a visit.