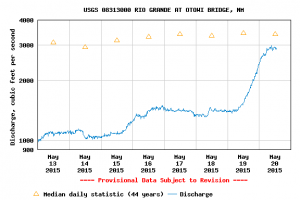

Water from our recent storms, combined with the some clever twiddling by federal and local water managers, is pushing the Rio Grande through Albuquerque in the next few days to the highest spring runoff levels we’ve seen since 2010. Water managers are taking advantage of the May storms to add some water and create a runoff spawning spike for the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers this morning increased releases from Cochiti Dam, north of Albuquerque, to 2,000 cubic feet per second, with as much as 3,000 to 3,500 cfs by tomorrow (Thurs. 5/21). Much of the water is a pulse of runoff from the mountains north of Santa Fe (Embudo Creek last night peaked at 1,000 cfs), but the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District are adding flows on the Rio Chama from El Vado Dam to create the spawning spike, which could hit 3,000 cubic feet per second at Central Avenue in Albuquerque by late this week or this weekend.

The remarkable turnaround is the result of a wet May (already the wettest May since 2007 in Albuquerque). Just three weeks ago, managers were scrambling for water, with little chance for a minnow spawning spike and with farmers in the middle valley on shaky ground. Now the farmers are hoping for it to dry out so they can get their alfalfa cut, and MRGCD storage upstream looks like it could have enough water, between native water and what they’ve been able to store in El Vado Reservoir, to last through the season (depending on the weather, I’m told – always depending on the weather).

The Rio Grande has spiked this high a few times in recent years as a result of summer thunderstorms and an epic September 2013 event, but this is the first time since 2010 that a peak this high has arrived at this time of year, which is the critical time for the minnow, an endangered fish whose status drives a lot of the politics and policy of the river’s management.