What to make of this California drought story from Alex Breitler?

Farmers within the Delta and farmers south of the Delta aren’t exactly bosom buddies.

Not when it comes to water.

But this spring, as their lawyers geared up for another year of fighting over limited supplies, farmers on both sides quietly started talking.

They hammered out a rough plan to compensate Delta farmers for voluntarily fallowing their fields, thus freeing up water that could be pumped south to their parched brethren.

The tentative arrangement was more complex than that — too complex, according to state officials, who rejected the plan late Wednesday.

But parties on both sides say the progress they’ve made could be helpful if, heaven forbid, the drought lingers for years to come.

The danger for me here is that the entire premise of my upcoming book is that collaborative arrangements to share water, rather than fighting, are the only way out of the mess we’ve made for ourselves. So obviously, in the midst of all the California hollerin’ right now, I love this story because it feeds my preconceived narrative. Most of my research right now is focused on deals like this, and how they come about – the formal legalistic (institutional) structures, but also the informal stuff. Great job Alex for this detail:

Farmers from both regions met recently on McDonald Island, toured the farms there and broke bread together (actually, they ate burritos).

Burritos! Yes! (For my book, beer seems to be the thing, though there’s an epic tale I may include involving mole at a Mexican restaurant in Salt Lake City.)

But there are two problems with the story that give me pause. The first is the obvious point that the deal didn’t go through. The state nixed it. I don’t see that as a huge problem. Part of what all these burritos, beer and mole are about is learning how to have the conversation. Alex’s story gets that:

While the plan appears to be dead this year, he didn’t rule out the possibility of another effort.

“We were trying to change the way we do this in California with more of a direct farmer-helping-farmer approach, rather than lawyer-talking lawyers,” he said.

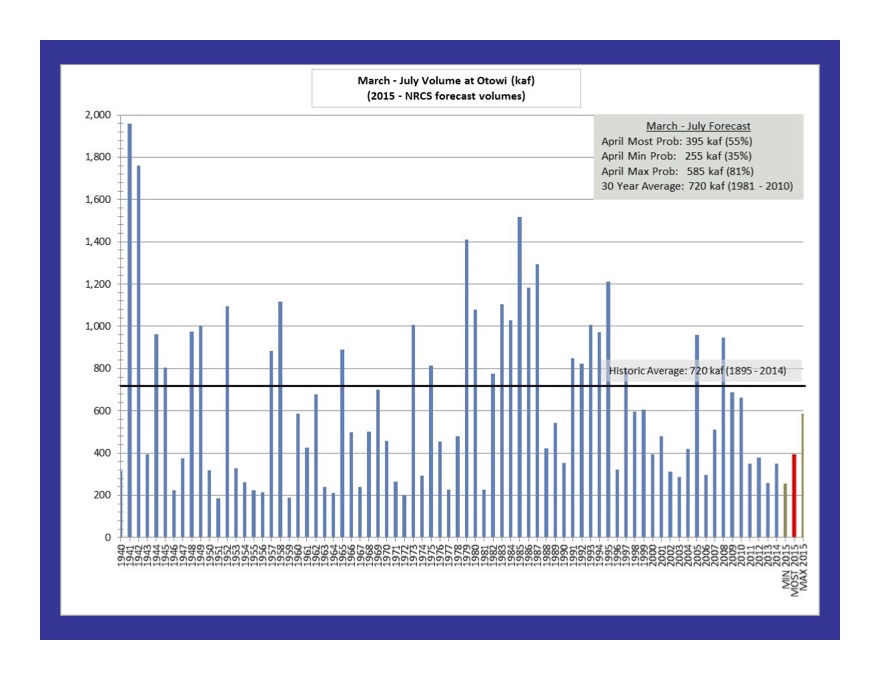

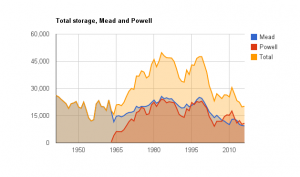

The second problem is more fundamental. Like some of the deals I’m looking at in the Colorado River Basin, this is a small deal. Are problems are huge. Does this approach scale up?