Brett Walton:

California, its hand forced in 2014 by a nasty drought, brought its groundwater laws out of the Gold Rush era and into line with nearly every other state in the Union. New York’s Democratic governor banned fracking for natural gas, in large part because of concerns about water pollution.

Kansas debated how to cope with a shrinking Ogallala Aquifer, its main source of irrigation water. Voters in California, Florida, and Maine endorsed new state spending on water conservation, water treatment plants, pollution cleanup, and river restoration. And more than one dozen states, spooked by drought and needing guidance, discussed or submitted new water plans.

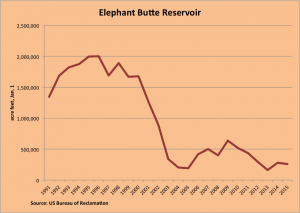

Taken together, these actions represent an awakening in the United States that water supplies are not as abundant as once thought. A series of severe droughts in recent years — from Texas in 2011 to the Midwest in 2012 to California today — is the frontline reality of a hotter, drier era that is forcing state leaders to take stock of their water assets and reevaluate laws, regulations, and investment strategies.

More is coming in 2015.

As outlined by Walton, much of the action involves spending on water infrastructure, but there are new planning efforts underway as well:

[S]everal states — Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, and Montana among them — will be finalizing water plans that were introduced in 2014. Both Arkansas and Colorado are proposing multibillion dollar infrastructure projects. In Arkansas’s case, new canals will wean farmers from unsustainable groundwater use. In Colorado, the growing cities of the Front Range are looking to move more water across the continental divide, from the Colorado River Basin.

But even there, as you can see, spending on infrastructure is a big part of the answer.

As usual, Brett’s article is worth a click and full read read.