By Eric Kuhn

The release of last week’s Bureau of Reclamation 24-month study felt like very bad news for the Colorado River (See Tony Davis for details.). But a careful reading of the numbers, and an understanding of the process through which they are developed, suggests things are likely even worse than the top-line numbers in the study.

The problem: the assumptions underlying the study do not fully capture the climate-change driven aridification of the Colorado River Basin. Taking climate change into account, it is easy to find evidence lurking in the report to suggest that, in addition to problems for Lake Mead, Lake Powell could drop below elevation 3,525 in 2023, a level that is troublingly close to the elevation at which Glen Canyon Dam could no longer generate hydropower.

The 24-month studies are used to project out two years of monthly inflows, releases, storage levels, and power generation from the system’s large reservoirs in both basins as well as diversions by the large water users on the river below Lake Mead, especially the Central Arizona Project and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. Reclamation releases a “most probable” study on a monthly basis as well as “minimum probable” and “maximum probable” studies approximately quarterly. These studies are important because they are used to make critical decisions under the 2007 Interim Guidelines and both the Upper and Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plans (DCPs).

For the first year, Reclamation uses “unregulated” runoff forecasts generated by the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center (CBRFC) model. Unregulated inflow is not the same as natural inflow. The CBRFC does its best to adjust the forecasts for upstream diversions and for the many reservoirs that are not included in the 24-month study model. Inflow forecasts for the second year of the 24-month studies are not based on the CBRFC model. Instead, Reclamation, in consultation with CBRFC, uses statistics from the past and its judgment. Running the 24-month study model then simulates the operation of the upstream reservoirs such as Navajo, Blue Mesa, and Flaming Gorge, turning unregulated inflow to Powell into “regulated” inflow. For example, from the April ‘21 most probable study, the WY 2021 unregulated inflow to Powell is 4.897 MAF, regulated inflow is 4.908 MAF. These numbers are close, but in WY 2020 regulated inflow exceeded unregulated inflow by about 700,000 acre-feet.

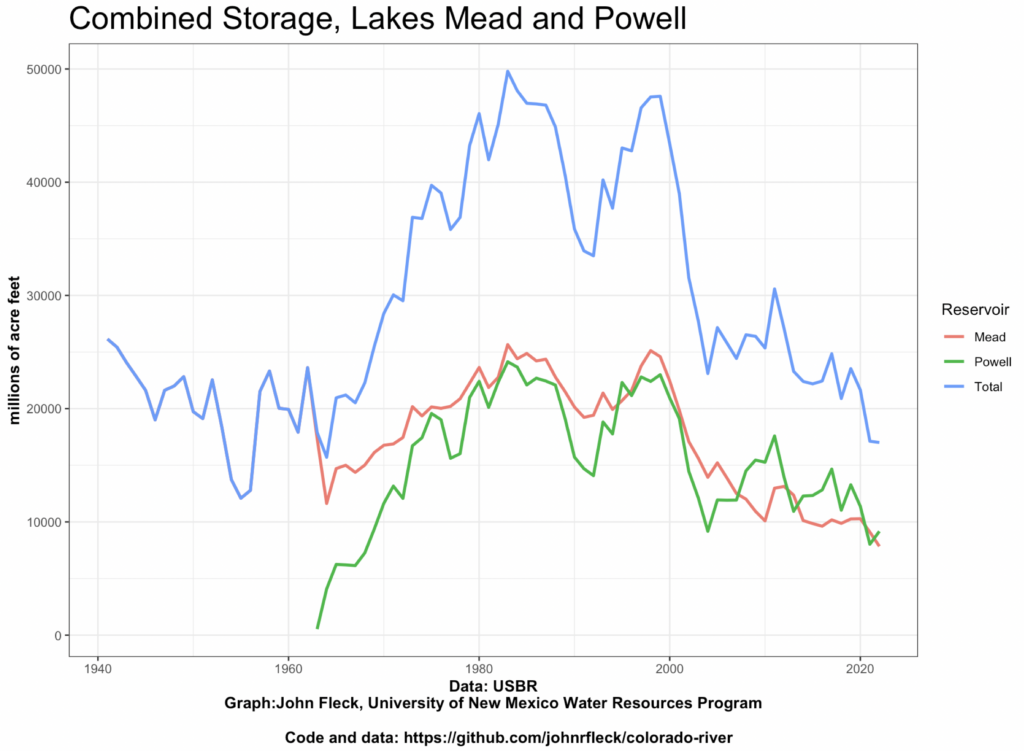

The media buzz over the April 24-month study primarily focused on the projected Tier 1 shortage for the Lower Basin in 2022 – an event that is newsworthy, but one that also was totally expected. Perhaps more interesting and alarming is what the 24-month studies suggested for 2023. As pointed out by John in his recent blog, the most probable study shows two years of 7.48 MAF releases from Lake Powell, Lake Mead elevations on the cusp of a Tier 2 shortage in 2023, and by inference, Lake Mead dropping to a level of about 1035’ by the end September 2023, which by implication would trigger a third straight shortage year and California’s possible participation sharing shortages under the Lower Basin DCP.

For Lake Powell, the most alarming results come from the minimum probable study, not the most probable study. Under the minimum probable inflow forecast to Powell, which, in theory, represents an unregulated flow that would be exceeded in 90% of years, by March of 2023 Lake Powell drops well below the 3525’ target that would trigger supplemental releases from the upstream CRSP reservoirs under the Upper Basin DCP. There is also a real possibility that Lake Powell could end up in the Lower Elevation Balancing Tier. If this happens, the April minimum probable study shows that Lake Mead gets more water in the first six months of WY 2023 than under the most probable study.

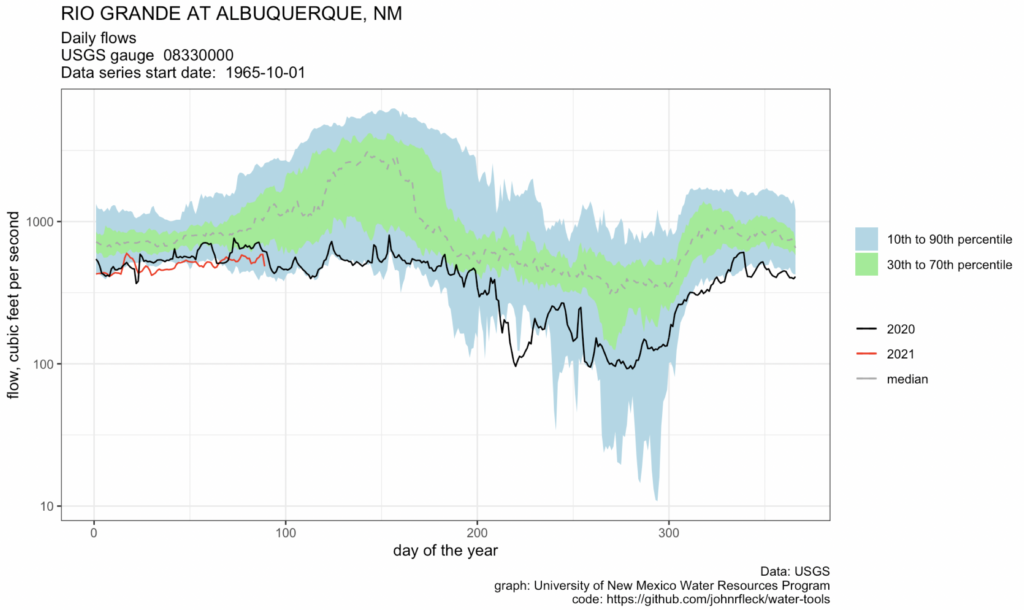

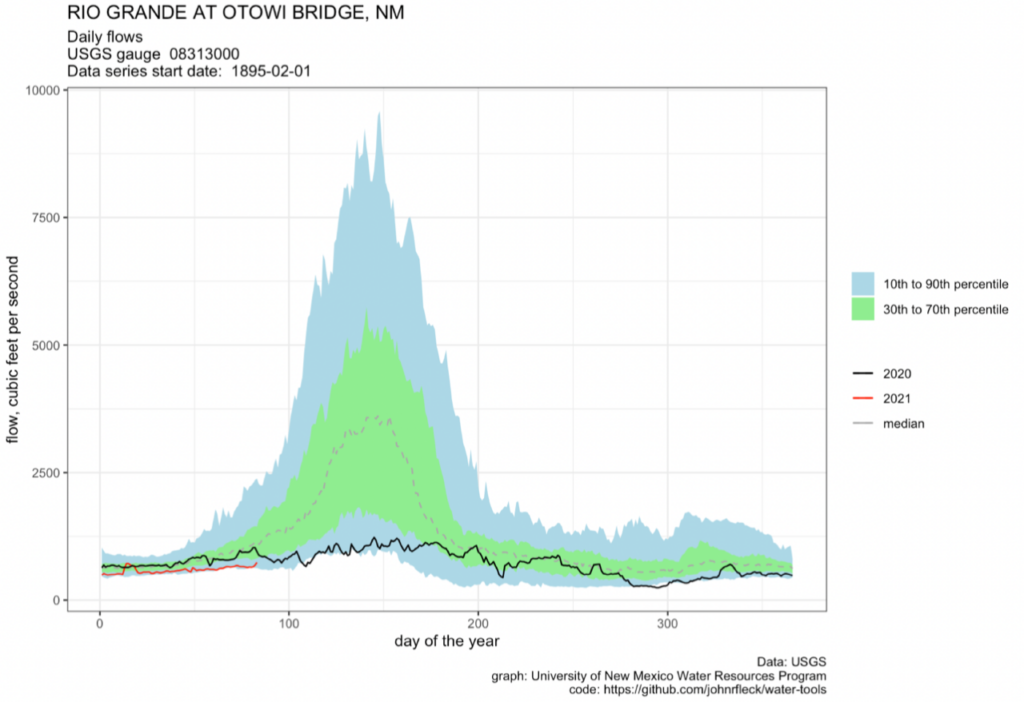

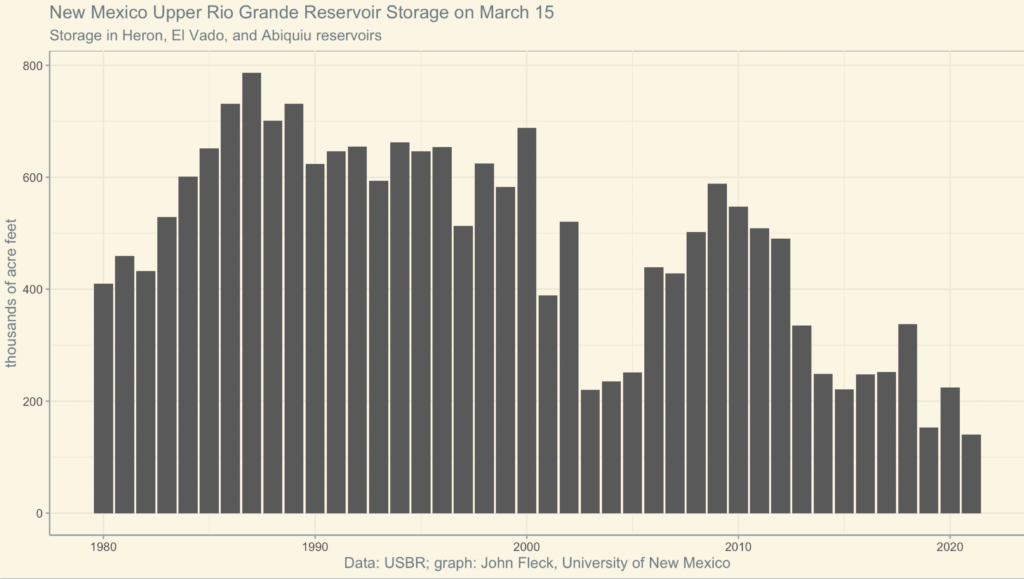

The term “minimum probable” implies an outcome that is very unlikely to occur, therefore, why should we be that concerned? My answer is that given the abundance of recent science concluding that the Colorado River Basin is not in a classic drought, but rather, it is undergoing aridification where the flows seen in the last two to three decades may be the new abnormal and may continue to decline (see for example Overpeck and Udall, and the latest Utah State Future of the Colorado River white paper White Paper). The April studies show a most probable Powell unregulated inflow for WY 2022 of 9.998 MAF and a minimum probable inflow of 7.208 MAF. For comparison, the mean unregulated annual inflow to Lake Powell over the last ten years, including WY 2021, was only 8.04 MAF and five of the individual years; 2012, 2013, 2018, 2020, and 2021, were well below the 7.208 MAF. The average of those five dry years was 5.08 MAF, over two MAF less than the assumed minimum probable inflow for 2022. If you take the record back to 2000, the results are similar. In 11 of 22 years, unregulated inflow to Lake Powell was less than 7.2 MAF/year.

Based on the last 20-plus years and the recent science, I conclude that both the minimum probable and most probable 24-month study year two unregulated inflows to Lake Powell are overly optimistic. The likelihood that in the next few years Lake Powell storage will fall below the 3525’ target or even the minimum power elevation (3490’) and that Lake Mead storage will approach 1025’, the level that triggers the maximum annual cutbacks under the Interim Guidelines and DCP, about 1.4 MAF, is much greater than what is conveyed by these studies.

A few years ago, Reclamation made the decision to begin using a stress test (1988-2018) in addition to the full “natural flow” record (1906-2018) for planning and project evaluation purposes. It may now be time for Reclamation to do something similar with the 24-month studies – base the year two unregulated inflow to Lake Powell on the post-2000 hydrology. This would not change the first-year decisions based on the 24-month study, but would help people in the basin better understand second year risks.