Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman

Catching up after a busy final week of the semester at the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources Program, I had time today to sit down and and think through the implications of this remarkable Bureau of Reclamation press release.

It did a great job of achieving one of the primary goals of a news release, capturing a news cycle with the message of increasing risk of a “shortage” declaration by 2020, which would impose water delivery cutbacks on Nevada, Arizona, and Mexico. (“Mexico, 2 U.S. states could see Colorado River cutback in 2020” was a common takeaway.)

But that news peg – a slight increase in the latest Bureau analysis of a risk we already knew was there – wasn’t really news. We’ve known that since January, and the latest numbers represent only a minor tweak in the direction of increased risk. The real action was in Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman’s use of the “press release” platform to issue a very public call for action.

“We need action and we need it now. We can’t afford to wait for a crisis before we implement drought contingency plans,” said Reclamation Commissioner Burman. “We all—states, tribes, water districts, non-governmental organizations—have an obligation and responsibility to work together to meet the needs of over 40 million people who depend on reliable water and power from the Colorado River. I’m calling on the Colorado River basin states to put real – and effective – drought contingency plans in place before the end of this year.”

Henry Brean did a nice job of capturing the key point:

The head the federal agency that oversees the Colorado River has a message for state water managers: The outlook is bleak, so quit squabbling and get back to work.

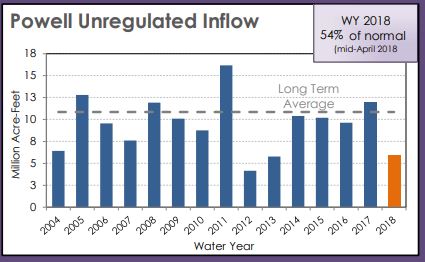

In a pointed message Wednesday, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman said drought and low flows continue on the Colorado with no end in sight, so it’s up to those who rely on the river to stave off a coming crisis.

This was not a traditional press release. It was more akin to what in linguistic philosophy they call “performative utterances”, where the act of saying a word also carries out the action the word describes. “I apologize” is the most memorable example. The news release is kinda like this. It doesn’t describe Burman’s call to action. It is Burman’s call to action.

And then Burman and her staff did something particularly clever. They got statements of support for early action on a Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan from representatives of each of the seven U.S. Colorado River states. One of the rituals for a reporter in a situation like this is to try to get everyone on the record. Whaddya think, is Burman right, do we need a Drought Contingency Plan right away? Burman and her staff did it for us!

My favorite is John Entsminger from Nevada: “This ongoing drought is a serious situation and Mother Nature does not care about our politics or our schedules. We have a duty to get back to the table and finish the Drought Contingency Plan to protect the people and the environment that rely upon the Colorado River.”

A year-and-a-half ago I wrote that a deal to reduce Colorado River water allocations was “inevitable”. The recent fracas in Arizona over details of such a plan had left me questioning that notion. It’ll be interesting to see how successful this effort by Reclamation is to clearing the logjam and getting a Drought Contingency Plan done.