The photojournalist’s mantra in the age of the ubiquitous mobile phone camera….

“the Eden of all bass fishermen”

One of my favorite bits of business that never made it into my Colorado River book was a late afternoon encounter at Lake Mead’s Boulder Harbor boat ramp with a guy named Scotty. I was thinking about Scotty when I came across the image below, in a 1946 Bureau of Reclamation report on the development of the Colorado River.

The Colorado Basin’s big reservoirs are the best measurement of the health of the hydraulic system on which the region’s farms and cities depend. Two things govern how much water sits in a reservoir – how much nature provides upstream, and how much people remove for use downstream. In the spring of 2015, as I stood at the bottom of the Boulder Harbor boat ramp, that health was not good. Looking up an adjacent hillside, I could see the high water mark more than a hundred vertical feet above me. The lake’s surface elevation, 1,088 feet above sea level, was the lowest it had been in any February since the dam’s federal managers closed its gates and began filling it back in the 1930s. Across the Colorado River Basin, combined storage in Mead and the Bureau of Reclamation’s other reservoirs, which when full hold about four years’ worth of Colorado River flow, stood at just 49 percent.

Scotty moved to Las Vegas after a stint in the Coast Guard and found a nice career supporting the convention industry. He comes down to the lake nearly every week to fish or boat. It is easy for outsiders to get caught up in resentment of Las Vegas, with its “sin city” reputation for gaudy excess, and to question why such our precious water should be squandered on such frivolity. But it is important to remember the Scotty’s of the world. To paraphrase the late Nobel laureate Theodore Schultz, people like Scotty are no less concerned above improving their lot and that of their children than the rest of us.

It was early in the season – late February, still too cold for the bass to be biting – when we talked as he pulled his little aluminum fishing boat out of the water at Boulder Harbor, the nearest boat ramp to his home in nearby Henderson. Henderson is the closest community in the greater Las Vegas metro area to Lake Mead, a quick drive through a treeless desert pass along Las Vegas Wash, around the south side of what the locals call “Sunrise Mountain”. The mountain is part of a treeless desert ridge that separates Las Vegas from a constant reminder of its vulnerability to drought – the great emptiness of Lake Mead.

On the north side of the harbor, against a bank lined with the high marks of old shorelines created as the lake receded, a swarm of ring-billed gulls poked at the water. Scotty pointed to the dipping and diving birds and explained that it was an early sign that the shad, a small non-native fish, were spawning. The bass would soon follow, and fishing season.

Scotty could remember the full days. When he came to Las Vegas in 1997, Lake Mead was more than a hundred feet higher than when we spoke. Locals would drive out the dirt road at Gypsum Wash to a spot where you could jump off a cliff eight feet into water. It used to be a favorite spot for shoreline fishing. Today, the cliff is 80 feet above a sandy wash.

At least Boulder Harbor is still usable. Just up the road, Gail Gripentog-Kaiser, whose family has run marinas and other recreational facilities on the shores of Lake Mead since the 1950s, packed up their floating docks and restaurants in 2002 and moved them to deeper water. A sign on the old the old Las Vegas Bay Marina floating restaurant read “Horsepower Cove or Bust” as the elaborate floating armada squeezed out the narrow neck of Las Vegas wash for a safer harbor.

Recreation brings Scotty to the lake, and gives him a tangible understanding of its decline. But it is the reservoir’s role as water supply to his adopted home, not its recreational value, that gives him pause. Scotty goes on line and tracks snowpack in the Rockies, the same way the water managers do, and talks idly about building a pipeline to the region to bring water from someplace wetter. But he does’t have much hope for a solution. “The writing’s on the wall,” he said. “There’s nothing we can do.”

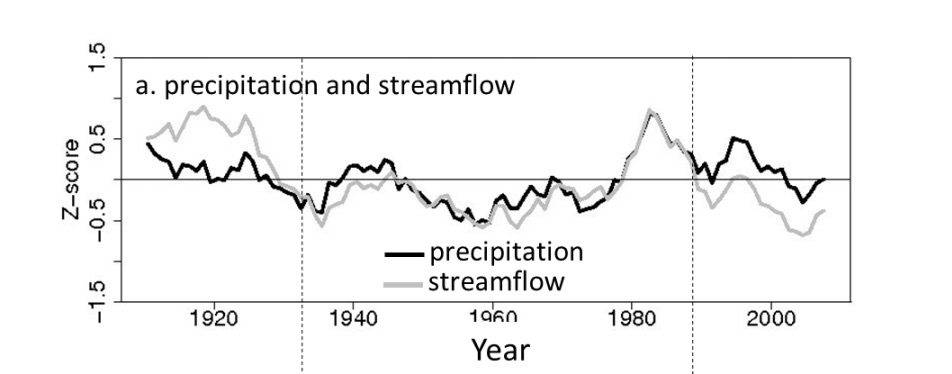

More evidence that climate change is reducing the Colorado River’s flow

Scientists for many years have projected a decline in the Colorado River’s flow as a result of a warming climate. But it’s only in the last couple of years that we’ve begun to see evidence that this is already happening.

The system has a lot of natural variability, so detecting the relatively smaller impact of warming amid the ups and downs of “did we have a lot of snow this winter or not” is hard stuff. But as the warming grows, so does the impact, and so does the detectability.

The latest, the third such effort, from the USGS’s Greg McCabe and colleagues, found a 7 percent decrease in the river’s flow in the past three decades as a result of warming temperatures.

Additionally, warm season (April through September) temperature has had a larger effect on variability in water-year UCRB streamflow than cool season (October through March) temperature. The greater contribution of warm season temperature, compared with cool season temperature, to variability of UCRB flow suggests that evaporation or snow-melt, rather than changes from snow to rain during the cool season, have driven recent reductions in UCRB flow. It is expected that as warming continues, the negative effects of temperature on water-year UCRB streamflow will become more evident and problematic.

Precipitation, primarily winter snow, remains the dominant variable influencing the Colorado River’s flow. But for a given amount of snow, we’re seeing less water in the river, a decrease in “runoff efficiency”.

The two previous papers that also showed this:

- Woodhouse et. al, Increasing influence of air temperature on upper Colorado River streamflow, 2016

- Udall and Overpeck, The twenty-first century Colorado River hot drought and implications for the future, 2017

on democracy

Erik Loomis is writing here about capitalism and socialism and forestry, but this generalizes:

[W]e need to value experts, not romanticize putting power in the hands of “the people,” which are not the figment of your projection about your own beliefs, but rather are the racist uncle at Thanksgiving and people who think The Big Bang Theory is hilarious and won’t miss an episode.

this was totally work related

A little “field work” yesterday morning, with one of our University of New Mexico Water Resources Program graduate students and a faculty colleague, looking at a potential environmental restoration site we’re studying.

The only way to get there was by bicycle.

Bummer.

When wastewater isn’t being “wasted”, Pasadena edition

Pasadena, California, wants to use treated effluent to water golf courses. This is a water policy no-brainer, right? Well….

“As part of preparations to commence deliveries of recycled water to Pasadena, the city of Glendale petitioned the State Water Resources Control Board to seek their approval for a reduction in the amount of treated wastewater discharged into the L.A. River so that it could be delivered to Pasadena. The city of Los Angeles is protesting Glendale’s petition, expressing concern that any reduced discharges of treated wastewater into the L.A. River could impact the preservation of the L.A. River and its habitats.”

Via my old friend Larry Wilson in my old employer the Pasadena Star-News. It’s a reminder that, in thinking about the values of reuse (and they are many), one part of the evaluation needs to be the question – where is the treated effluent going now, and what effect will our golf course use have on that?

California’s private utilities out-conserved its public utilities during the drought

If you had asked me to guess whether public or private utilities did better at water conservation, I would have without hesitation guessed that public utilities did better.

So here’s a fascinating result from Manny Teodoro and Youlang Zhang of Texas A&M, looking at data from the recent California drought:

[O]n average, communities served by private utilities adopted more stringent conservation regulations than those served by public utilities; and so … private utilities were significantly more likely than their public counterparts to meet the state’s conservation standards; and … private utilities on average conserved more water than public utilities. Somewhat counterintuitively, then, private, profit-driven firms were more effective than were local government agencies in achieving the state’s conservation goals.

The working paper, Privatization as Political Decoupling: Water Conservation and the 2014-2017 California Drought, is here. Their argument is that, for a public utility governed by directors facing reelection, rate increases and other conservation constraints on consumers pose political risk. Private utilities, on the other hand, offload that political risk to a state regulation commission, which governs their rate setting.

We argue that, where policy goals can be achieved through regulation of private firms, private provision of public services allows governments to separate public policies from their political costs. By shifting production or service provision from the public to the private sector, governments can achieve policy goals through regulation, while shifting the accompanying political risks to the private sector, where they are less acutely felt. The result is a political decoupling that allows governments to achieve policy goals while insulating officials from their political costs. One implication is that, where financial decoupling exists, regulated private firms are more likely to comply with environmental regulations than are government agencies, because the latter bear electoral costs that the former do not.

This result makes sense, though it is not at all consistent with my naive expectation. But it is consistent with a similar finding from Megan Mullin and Meghan Rubado, who found that water agencies with directly elected boards of directors in Texas responded more slowly to drought.

Fish returning to the Fraser in one of Colorado’s high mountain valleys

An example of what can happen when folks stop fighting over water and search for common ground paths:

Now, instead of a wide shallow creek, the low-flow Fraser River drops into a narrow channel that allows to run deeper, faster and colder. That led to a nearly immediate rebound in the fish population, according to a preliminary assessment by Colorado Parks and Wildlife.

“We found about a four-fold increase in trout population,” said Jon Ewert, an aquatic biologist at CPW who surveyed the river both before and after the project was finished. “It was pretty exciting to see that.”

This arises from a collaboration between environmental groups and a municipal water agency, Denver Water. These folks had been at odds for a while. This is an example of the point Jennifer Pitt made in Tony Davis’s recent piece about Minute 323, the U.S.-Mexico Colorado River agreement:

Pitt warned that if governments and water users end up fighting over a dwindling supply, the environment will be the biggest loser.

“No politician can support nature when communities are threatened by a water supply crisis,” she said.

Two cautions here on the Fraser story. First, it’s just a tiny bit of data. Second, it’s just a tiny bit of river. But it nevertheless is progress.

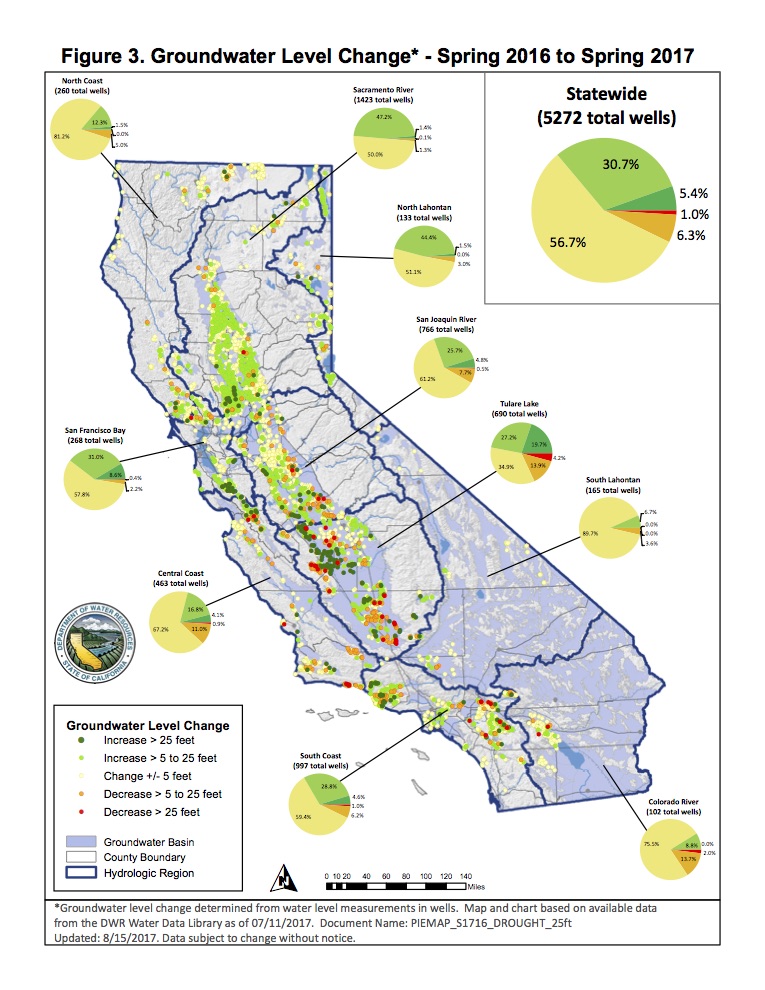

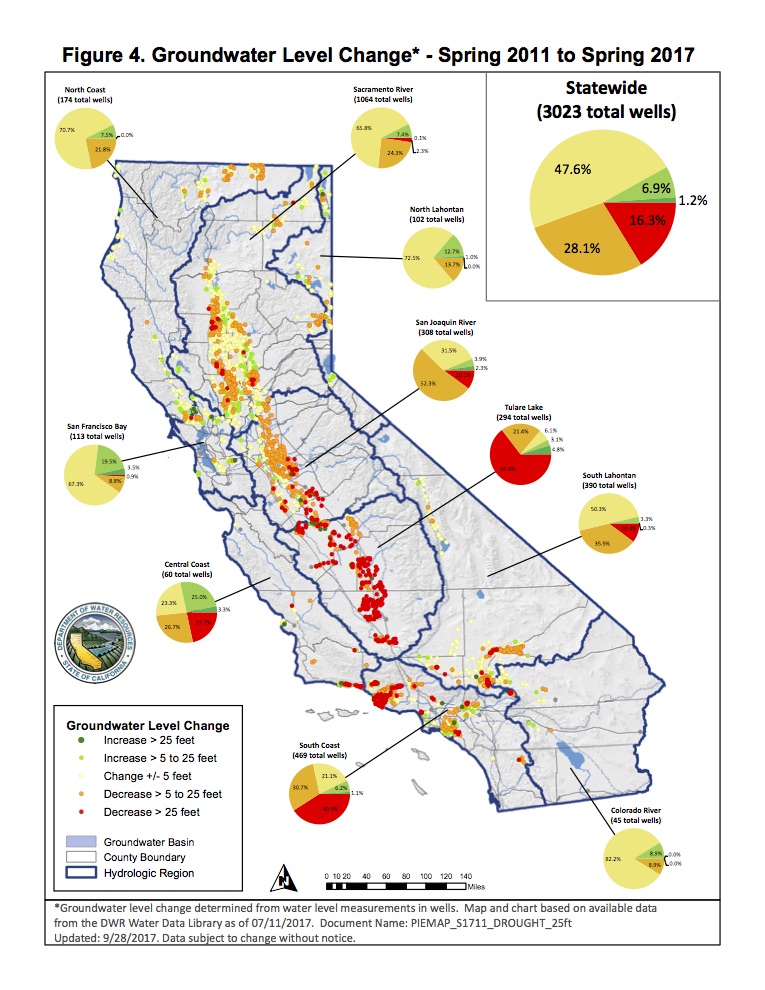

It takes more than one year to dig out of California’s water hole

California has seen excellent groundwater recovery in the last year, according to a report last week from the California Department of Water Resources:

But it’ll take more than a year to dig out of the hole left by the massive groundwater pumping of the last 6 years:

From the report:

While images of filling reservoirs and rushing rivers seemed to be everywhere earlier this year, groundwater levels reflected the differing hydrologic conditions of individual groundwater basins. Although water levels in shallow basins may quickly show marked improvement, deeper, severely depleted groundwater basins may take years to recharge.