At the end of April, Lake Mead sat at 1,085 feet above sea level, more than eight feet higher than it was a year ago. That is in part thanks to a big winter upstream, which has ensured continued above-average releases from Lake Powell upstream.

But equally important is the fact that folks in the Lower Colorado Rive Basin are using less water.

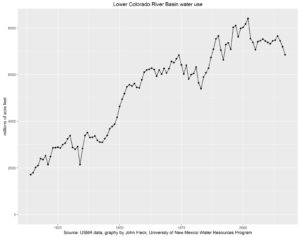

Lower Colorado River Basin water use (2017 forecast)

According to the current Bureau of Reclamation Forecast, water agencies are expected to take 6.849 million acre feet of water out of Mead this year to supply farms and cities in Arizona, California, and Nevada. If the forecast holds, that would be the lowest Lower Basin use since 1992. As Tony Davis has pointed out, we need to be careful about putting too much stock in these forecasts this early in the year. There is a lot of water allotment juggling underway right now, including questions about how much Northern California’s wet winter will allow the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California to leave extra “intentionally created surplus” water in Lake Mead, and the ups and downs of Imperial Irrigation District’s use as it adjusts to changes in its water-saving fallowing program that kick in beginning July 1.

But the preliminary forecast can give us at least an inkling of where the water savings are coming from:

- Metropolitan Water District (southern California municipal water) is currently forecast to take 522,000 acre feet of water, which would be its lowest year since as far as my records go back, which is to 1964. This could change – lots of discussion now about Met’s approach to storing surplus water, and there are indications elsewhere in the Bureau’s water forecasting system that Met’s take could be as high as 768,000 acre feet – but no matter how things end up, Met will likely have a very low water use year, well below its 937,000 acre foot per year 21st century average.

- Central Arizona Project is forecast to take 1.506 million acre feet, roughly the same as the last couple of years, about 5 percent below its 21st-century average.

- Imperial Irrigation District is forecast to take 2.5 million acre feet. This is 20 percent below its 2003 peak – Imperial’s a remarkable case study in agricultural prosperity in the face of reduced water availability.

Overall, under the current forecast Colorado River water use in Nevada, California, and Arizona would end the year 18 percent below its peak in 2002.