Riding my bike late this morning, I stopped to admire a roadrunner in the trail.

Roadrunner with fish.

As you can see from the picture, it’s a ratty bit of trail (Gritty? We have more words for the sublime than the mundane.) flanked by the freeway to the north and a treeline to the south bordering old farm fields, a remnant of what this valley once was.

I waited and watched, and when the bird finally emerged into the sun, I could see that it was carrying a small dead fish in its beak.

What to make of this, a desert bird carrying a fish on an urban bike trail?

Much of Albuquerque’s valley floor is covered with houses now. These aren’t recent tract homes. Suburbia in its modern form has been overtaking the farms of the valley here for a very long time. But if you look closely, you can see traces of the old irrigation ditches. Sometimes it’s just a treeline that follows the path of a long-gone irrigation system. Often it’s still a ditch – water still flows through this valley in ditches maintained by the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, some the same ditches the water has traveled for more than three centuries. The ditches have become an urban amenity, a park-like setting in the midst of the arid high desert, flowing through neighborhoods that are sometimes wealthy and sometimes not.

neighborhood ditch

On time scales not that hard to imagine, the land on which these neighborhoods and this bike trail sit, where the roadrunner carried a fish back to the nest for its babies, was the river itself. The “river” as it now flows, controlled by dams upstream, reduced in size by farming in the San Luis Valley of southern Colorado, and hemmed in today by levees, was about a half mile behind me as I straddled my bike and pulled out my cell phone to snap a picture of the roadrunner.

A few years back, we had a fascinating environmental politics kerfuffle here in Albuquerque over plans to build a trail through the woods that flank the main river channel through the center of town. A Republican mayor was pursuing the trail, with strikingly virulent opposition from a coalition led by the local chapter of our Sierra Club. “The thing that makes the Bosque the place that we all love is that it is an unsurpassed urban space for the enjoyment of nature,” the campaign’s leader, Richard Barish, wrote. “Any project should not diminish that experience of nature.” It was old-school environmentalism, about saving the wild places among us, and for a segment of the community it resonated, leading to the largest level of local environmental activism I can remember in my years here.

I will declare my view of this controversy clearly here: moments before I came upon the roadrunner, I had been riding what we have come to call “the mayor’s trail” through the woods of the bosque, and I loved it. The Rio Grande is up, swelled with the biggest spring runoff in a decade, I had to take two detours to get around the places where water had swamped the trail, and it was delightful. The new trail is one of the best places in all of Albuquerque to get down to our river, and I delight in getting down to our river.

But I am also mindful of the important questions the environmental historian William Cronon raised in his famous 1996 essay “The Trouble with Wilderness“:

By teaching us to fetishize sublime places and wide open country, these peculiarly American ways of thinking about wilderness encourage us to adopt too high a standard for what counts as “natural.” If it isn’t hundreds of square miles big, if it doesn’t give us God’s eye views or grand vistas, if it doesn’t permit us the illusion that we are alone on the planet, then it really isn’t natural. It’s too small, too plain, or too crowded to be authentically wild.

I was reminded of Cronon’s essay by a conversation with Samuel Truett, a University of New Mexico environmental historian and former student of Cronon’s who I met by chance on a walk to the river Friday afternoon. We were both speakers at the fascinating Decolonizing Nature conference organized by colleagues at the university. Feeling a bit socially overwhelmed (I am an introvert, these things are wonderful but exhausting) I snuck out and walked to the river, which was just a few hundred yards from the hall where the conference was being held.

In my talk, I reminded the audience that the river was not merely “over there”, across a fence, a bike trail, a ditch, and a levee. Were it not for human intervention, it would be flowing over the land where the buildings of Albuquerque’s National Hispanic Cultural Center, the lovely conference site, now stands. We were in the Rio Grande.

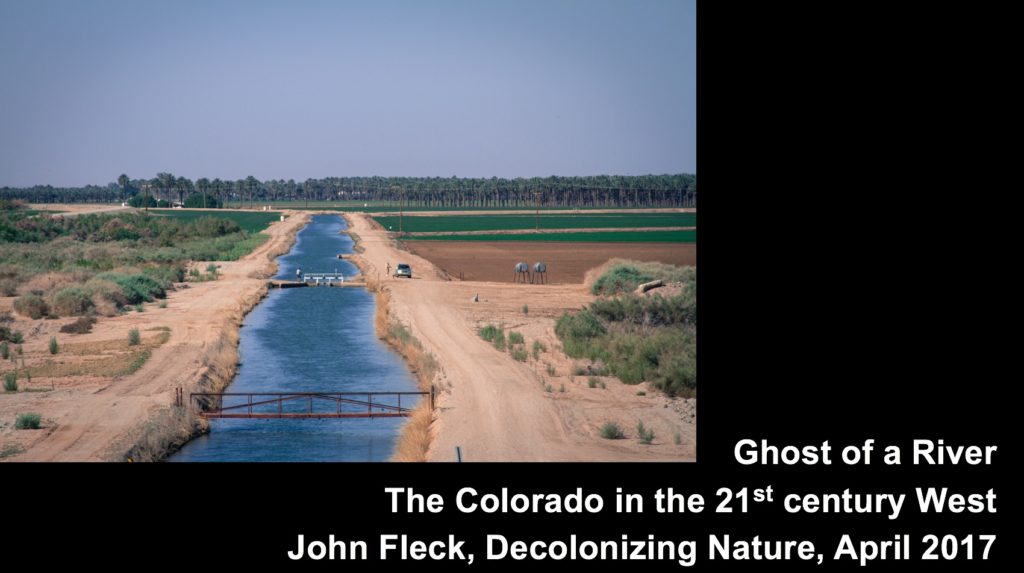

Colorado River flowing beneath the I-10 bridge at Blythe, February 2015

This is at the heart of what I’m trying to think through for my new book. “The Ghost of a River” is as good a working title as any right now. It’s rooted in my shifting understanding of rivers, in the pain of first seeing the end of the Colorado River at Morelos Dam – “This great river, the Colorado,” I wrote in my book, “around which I have spent much of my life, whose water I have showered with and drunk, which has grown the food I eat and floated my boats for hundreds of miles, simply disappears into the desert sand.”

Walking down into the bosque Friday afternoon, I led a group of folks from the Decolonizing Nature conference to a spot where overbanking water from this year’s big runoff had reclaimed a low spot that was likely the path of an old irrigation system that predated Conservancy District, levees, cities. It is impossible to separate the “natural” from the human here. My new project involves an effort to ignore the distinction and think about rivers in their human form – an irrigated lettuce field in Yuma every bit as much a part of the Colorado River as the water flowing through the main channel beneath Yuma’s old railroad bridge.

One of the people with us – I did not get his name – was puzzled by this river, shallow water barely moving. It was not what he had expected when led on a walk to “the river”. I explained that the “river” he was expecting was just over there, beyond those trees, but that there was no way to get to it without getting your feet muddy, because the river had reclaimed the bosque at our feet.

I love the bosque, the trees of the river corridor itself. I love that there’s a nice manicured trail through it so that I can ride my bike. I love that in places the river has reclaimed the trail, delighted by my need to detour. I’m increasingly interested in inquiring into the idea that the spiderweb of pipes and canals that move water through the human systems we’ve built around it is in some sense part of what we mean by “the river” now too.

Somewhere off the bike trail, that roadrunner found a little fish in an irrigation ditch. Is this “natural”? Dunno, but it’s interesting.