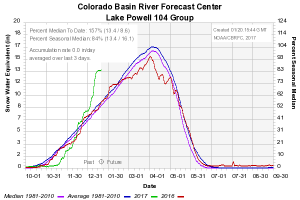

At this critical time of year for Colorado River snowpack, things are looking very good. For the first time this year, the April-July runoff forecast has climbed above 10 million acre feet.

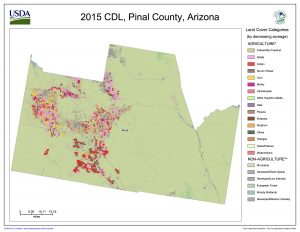

Snowpack above Lake Powell, courtesy CBRFC

The snowpack among the sites above Lake Powell where the federal government maintains real-time monitoring equipment is 57 percent above the long term median for this point in the year.

The amount of snow does not translate directly into river water because of a number of mediating factors – dry soils going into the season can soak up some of that, and warmer temperatures mean greater evaporation. That said, however, the latest model runs by the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center put April-July runoff at 40 percent above average. That’s the 10maf runoff forecast.

But since a key thing in water management is to enjoy the best but be ready for the worst, the most important thing in the CBRFC forecast is the forecasters’ bad news scenario. They calculate not only the most probable runoff, but also a sort of “worst case”, something you would expect in the driest 10 percent of years. That worst case right now is for above average runoff in the Colorado River Basin.

Here’s how this translates to policy, and why this is especially good news for those in the Lower Colorado River Basin trying to cope with the decline of Lake Mead. The nominal required release (shut up lawyers, I know that’s a contested characterization, let’s just go with it) from Lake Powell to Lake Mead each year is 8.23 million acre feet per year. When there’s more water in Powell, we move “bonus water” downstream, and lately there’s enough for 9 million acre foot releases. The current snowpack pretty greatly increases the probability of 9maf releases for the next couple of years, which makes it much easier to keep Mead from slipping into shortage.

The 1-in-10 best case scenario is nearly 13maf. Under Mead-Powell operating rules, a year like that would mean far more than 9 million acre feet for Lake Mead, which combined with current conservation efforts would buy the Lower Basin years of cushion before shortage.