A desert landscape. Corrales, New Mexico, January 2023. Photo by John Fleck

Writing in 2018 in the Seattle Journal of Environmental Law, Kait Schilling argued that the doctrine of prior appropriation – the notion that those who first put water to use hold priority over those who came later – was no longer compatible with a climate-changed world.

Climate change is diminishing water rights equally regardless of date of appropriation. Such a phenomenon makes the “first in time, first in

right” rule difficult to grapple with because right holders will be unable to access their water to its fullest extent. Because every human has a right to fresh water, the first in time, first in right mentality can no longer be sustained with the current state of climate change and population growth.

The two sides of the argument:

- equity requires sharing the pain across all water users – seniors (mostly farms but also Native American communities) and juniors (mostly cities)

- to respond to climate change-induced shortages, we need to cut off juniors, or make them compensate seniors for the water they need

This debate is the narrow eye of the needle we’re trying to pass through right now in the rapid-fire negotiations underway to deal with this Colorado River crisis.

The sticking point in the current Colorado River negotiations

In a letter submitted to the U.S. Department of the Interior in December, Arizona’s water leadership – the Department of Water Resources and Central Arizona Water Conservation District – argued for “1”. (Huge thanks to Daniel Rothberg at the Nevada Independent for collecting and posting the letters and also writing some smart stuff about what’s in them – journalism as a public good. The context here is Interior’s request for scoping comments on the agency’s crisis management Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement – SEIS):

All water users share risk from these conditions and the SEIS should ensure that the burdens associated with managing that risk are shared across all sectors and by all water users.

In their letter to Interior, the staff of the Colorado River Board of California argued for “2”:

Finally, some across the Basin have advocated for Lower Basin water users to be individually assessed for reservoir evaporation, seepage, and other system losses. The Board recommends that these losses continue to be treated as a diminution of available annual supply, which can then be met through application of the Law of the River as supplemented by voluntary agreements.

I plead guilty to a misleading oversimplification here, because in their arguments both Arizona and California are making a broader argument about equitable sharing of both the impacts of climate change but also the underlying problem of the river’s overallocation. In defense of my oversimplification, I’ll simply assert that it is the “hot” part of our “hot drought” (see Udall and Overpeck 2017) that makes the difference between the successful gradual process of negotiation we’ve using for more than two decades (see my book Water is For Fighting Over) and the crisis management of 2023.

Could a decent snowpack widen the eye of the needle we must thread?

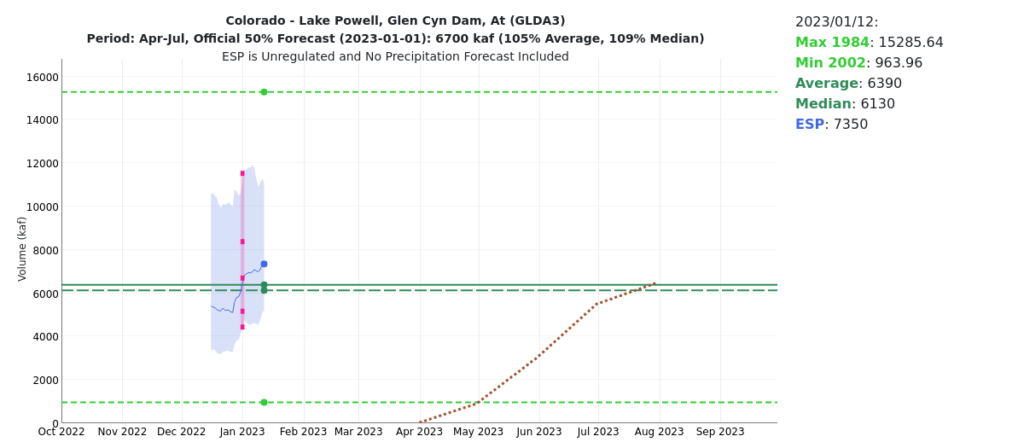

An improving forecast. Source: Colorado Basin River Forecast Center

Curled up with my morning coffee this morning (with a huge thanks to the supporters of this blog who bought it for me), I was happy to note that the snowpack is decent right now, and therefore the Colorado River runoff forecast, is up 650,000 acre feet from Jan. 1. That’s an extra ~10 feet of elevation in Lake Powell, which is ~10 feet farther from the white hot fire of crisis management at Glen Canyon Dam.

One argument here is that even a decent year, by lifting the pressure on Glen Canyon Dam -> more water to Lake Mead -> less pressure for really deep cuts now -> less risk of litigation. (I have my own views on this argument – I disagree with it, which I’ll explain below – but I’m trying to do the “view from nowhere journalist” thing here, and I want to give the people I disagree with their best shot, because the argument is not unreasonable.)

The litigation risk

In its EIS comments (see Daniel’s excellent work, did I mention its useful excellence? for the link), the Southern Nevada Water Authority laid out a plan calling for extremely deep cuts regardless of what the near term snowpack and runoff looks like – ~2.6 million acre feet of Lower Basin cuts from the states’ baseline allocations, essentially now. I’m torn between two similarly useful metaphors for what Southern Nevada says is needed – “ripping the bandaid off” and “a tourniquet, not a bandaid”.

In laying out its argument, Southern Nevada does version “1” above, much like the language of Arizona’s letter to Interior, with a call for distributing a portion of the cuts (those allocated to evaporation and system losses) sorta evenly across all water users.

I made much the same argument in my December letter to Interior, so I’m sympathetic to distributing the evaporation and system losses across all users before we think about allocation of the next level of cuts needed.

But here’s the thing that’s wrong with my argument.

To do that, you have to step outside the doctrine of prior appropriation. And the seniors – everyone mentions Imperial Irrigation District at this point, but they’re not the only senior with smart lawyers being asked to take cuts in this scheme, most notably Native American communities, who have deep legal and moral standing – will sue.

Flip the script, though, and try to take tourniquet-level cuts without spreading them broadly and you probably have to dry up the Central Arizona Project canal. Cue the “they’ve got smart lawyers and will sue” song. (To further complicate things, that would jeopardize the rights of Native American communities in Central Arizona that get their water through the CAP!)

This is the argument my smart friends who disagree with me make: A decent runoff this year would allow us to make more modest cuts (still substantial, but not nearly as deep) while avoiding tangling up the whole mess in the courts. I disagree, as I’ll explain below, but it’s not an unreasonable argument.

On bandaids and tourniquets

Obligatory “dancing with dead pool” visual reminder

In my comments to Interior, written in a Covid fever in December, I made an argument strikingly similar to Southern Nevada’s (“There was no collusion,” Fleck pleaded. “It’s just arithmetic!”) – that we need deep cuts now and forever. This is the tourniquet argument, and why I disagree with the “take advantage of a decent snowpack to make more modest cuts and avoid litigation” argument. The “now” part is because we’re staring down dead pool, and the “forever” part is that the river was always overallocated, and with climate change it’s now really honest truly overallocated for sure.

Even if we have a decent snowpack, I believe it is imperative that we use that water to refill reservoirs rather than irrigate alfalfa and lawns.

I’m genuinely concerned about throwing this whole thing into the courts. As we learned with Arizona V California six decades ago, litigation is a terrible way to manage a river. Much of our dilemma today is a result of the Supreme Court ignoring arithmetic and allowing us to overuse the river’s water.

My friends who argue for taking advantage of a bit of extra water, if we’ve got it, to try to stay out of court are not making an unreasonable argument.

But we can’t entirely blame the Supreme Court for our troubles. Part of today’s dilemma is the result of our failure to do the hard work of grappling with the court’s mistakes and sufficiently reduce our use of water. We’ve been avoiding litigation for too long by emptying the reservoirs and letting people use the water to irrigate alfalfa and lawns.

Always thoughtful John. Well done.

One of the on-going challenges with coming up with a good compromise is many of the observers, and a surprising number of the participates, do not see or understand 2 basic truths:

1. If Reclamation, or any federal agency, does a “taking” it does create a situation that will almost surely end up in SCOTUS. (you said this much more eloquently)

2. If it does end up at SCOTUS, the odds of them creating new law is very low, and they will likely go back to the last settled ruling, which would be back to 1922 Wyoming v. Colorado, and we still end up in Prior Appropriation land.

Prior Appropriation may not be the long term solution, but it will likely be a basis for determining who has power in the final agreements.

Full disclosure here: SDCWA’s lease/purchase of IID water rights allow me to take a shower each night, and pay some of the highest water rates in the country. So I both benefit, and suffer, under the current system.

The good stuff, John. Care to comment on the role of good coffee in provoking these thoughts?

Option 2 leads us down the road to “The Water Knife” and while IID (and others including SDCWA as mentioned above) may well win with SCOTUS, that solution has myriad consequences that are worse than what Option 1 would bring. I think the legal concept of reformation may be one way to resolve this in the courts. The basis of the 1922 compact was flawed from the start and is more flawed now that we have changed the climate. My understanding is that the cutbacks contemplated in the compact were for shorter term supply challenges, not a permanent diminution of 15MAF down to 12MAF per year. To me, and for full disclosure my law degree is from the University of Wikipedia, this is a changed circumstance that the courts should reckon with. Of course Congress could probably step in, but….

AS I said 12 years ago, they should have cut all water users back 10% across the board. Any manager can figure out how to live with 10% less. If that happened there would be approximately 15-16 MAF still in the reserviors. The only thing to do now is major cuts. And you can only let the amount of water pass through the dams what comes in from upstream. It is going to hurt.