update: A correction to this post here, thanks to some excellent journalistic sleuthing by Tony Davis.

****

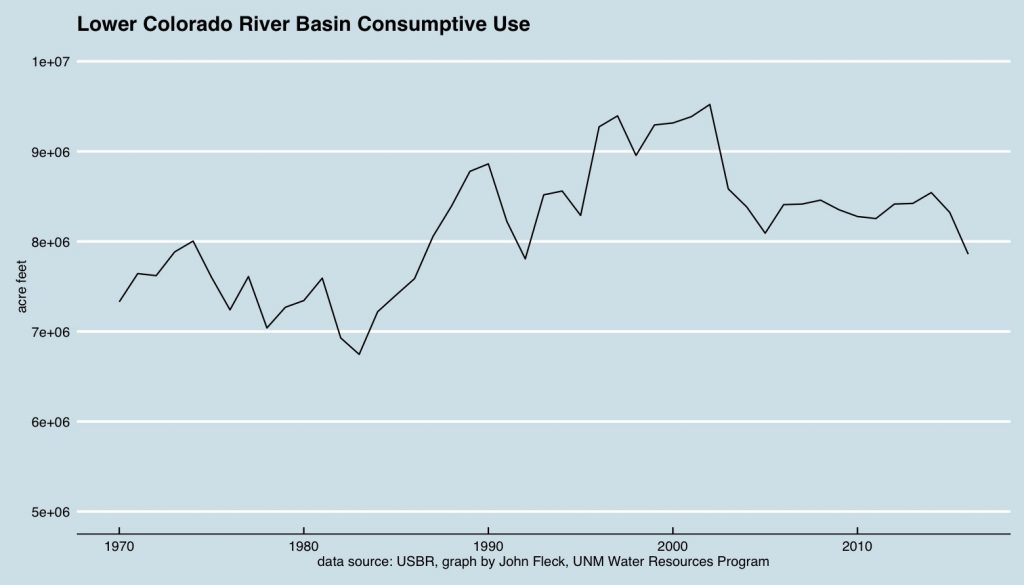

The Bureau of Reclamation’s Aug. 1 Colorado River Lower Basin Water Use Forecast (pdf here) passed a symbolically important milestone: at a forecast consumptive use of 6.998 million acre feet, if the forecast holds, this will be the first time Lower Basin use has been below 7 million acre feet since 1992.

Water use in 1992 was down because it was an extremely wet year. In Arizona, for example, it was one of the three wettest years in the last half century. This year has been dry. Water use is down because water users across the basin are cranking down their water use to try to keep Lake Mead from dropping further.

Here’s the data, with consumptive use in Nevada, Arizona, and California, plus reservoir evaporation in Lake Mead and the major reservoirs downstream – 7.858 million acre feet this year, compared to 7.806 maf in 1992. It’s a 17.5 percent decrease in water consumption since the 2002 peak:

Lower Colorado River Basin water consumption

Since 1992, the population in the major metropolitan areas served with Lower Basin water – LA-San Diego, central Arizona, and Las Vegas – has grown from 19 million to 26 million. That’s pretty striking – 7 million more people using essentially the same amount of water.

One of the central arguments of my new book Water is For Fighting Over is that when people have less water, they use less water – that we have the ability to significantly reduce our water use in the arid West and still thrive, and that we are in fact already making significant progress. That’s what’s happening in the graph above.