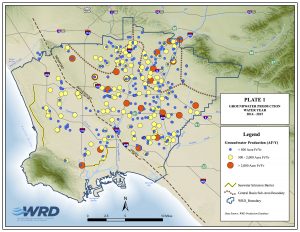

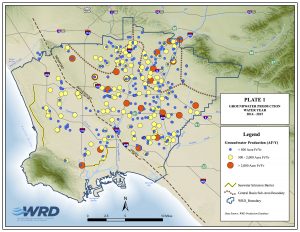

Steve Scauzillo wrote last week about the Water Replenishment District of Southern California’s decision to invest $110 million in a new wastewater treatment plant, that they might use 21,000 acre feet now discharged to the ocean to recharge regional aquifers instead.

Water Replenishment District of Southern California

Formed in the early 1960s, the WRD is the best example of one of the places where Californians do regulate their groundwater. In the rhetoric around California’s groundwater management failures, the Central Basin and West Basin agency, which spans the core of the Los Angeles metro area, is sometimes missed. I suspect that’s because they’ve been doing it for so long it’s just taken for granted. But as California struggles with setting up groundwater management in places it hasn’t done it before, there are lessons to be learned in the places that it has.

I’d love it if you could at this point just buy my book so you could read the chapter about the formation of groundwater governance in this region, but it’s not out yet (preorder now!), so at the risk of giving away important content for free…. Southern Californians created what Elinor Ostrom and colleagues might have called “covenants without a sword“, which is to say binding agreements among water users in the basin to regulate groundwater pumping and collectively act to manage the aquifer through an extensive recharge program along with creation of seawater barriers to prevent saltwater intrusion, but without the heavy hand of the state of California acting as an enforcer (the “sword”). Instead, the water user community polices itself.

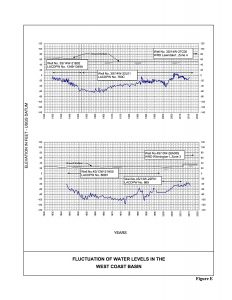

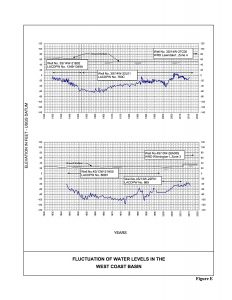

West Basin groundwater levels

This goes back to the 1930s and ’40s, when communities in West Basin, out near the coast, saw groundwater levels dropping and saltwater intrusion threatening their groundwater supplies. Ostrom’s doctoral thesis documents the struggle to create governance institutions that avoided a “tragedy of the commons”. By the 1960s and ’70s, the communities had set management goals for their aquifer that restricted pumping, managed recharge, and treated their aquifer as a valuable reservoir and storage reservoir that could be used as a sort of “working reserve” that fluctuates up and down in response to the availability of surface supplies. The aquifer is not off limits completely. Rather, it’s managed in conjunction with other supplies to ensure a sustainable water supply for the region.

The Albuquerque example

My own city of Albuquerque has been engaged in a successful aquifer management effort over the last decade (I’ve written a lot about this here at Inkstain, and of course pre-order my book for more, Albuquerque’s success is in some ways both the rhetorical starting point and ending point for the book’s argument) that has some similarities. John Stomp, our water utility’s Chief Operating Officer, spoke to my UNM Water Resources Program class last fall about the new Water Resources Management Strategy now in development, which looks increasingly like what they’ve done in West Basin. (disclosure: In my post-journalism career, I’ve recently begun working with the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority doing some technical writing on the WRMS. Disclosure 2: Some of my smart New Mexico water friends are less enthusiastic than I about Albuquerque’s approach, Dennis Domrzalski explains their concerns here.)

The new wastewater recycling Scauzillo writes about is not the first time they’ve done that. In fact, they’ve been doing that for decades, averaging 55,000 acre feet per year. But they also still use some imported water (Colorado River and State Water Project supplies, which come from Northern California). The new project will mean the replenishment is entirely weaned from that imported water.