Hanak on the risk of groundwater regulatory overreach

It’s tempting during a drought to call for pumping restrictions, but this can worsen economic impacts, especially on the farm sector. Now is a good time to take actions that ensure groundwater is available for future droughts.

On the need for better water data

A student in one of our University of New Mexico Water Resources Program classes asked last week what the magic trick was to finding water data. We’d asked the students to do some really challenging modeling of the flow of water through New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande watersheds, and one of the biggest difficulties was finding usable data to plug into their models. My faculty colleague who’s helping teach the class (and who is one of the great data wizards of the Middle Rio Grande) didn’t have a good answer. Like all of us, he’s collected spreadsheets and bookmarks over the years that point in the right direction, but each question leads to a new data need. Water data is hard. Often it’s not collected at all, and when it is, it’s not standardized and connected up in ways that might make it accessible.

The result is that important policy questions – how might climate change impact agricultural acreage, or the need for groundwater pumping? what role might direct potable reuse of wastewater play? our students are smart, these are the kind of questions that interest them – are very hard to ask in any sort of a quantitative way.

My experience working with Western water data thus leaves me enormously sympathetic to the argument Charles Fishman made in yesterday’s New York Times about the need for better US water data:

Water may be the most important item in our lives, our economy and our landscape about which we know the least. We not only don’t tabulate our water use every hour or every day, we don’t do it every month, or even every year.

If you’re willing to put in the work, the problem can be tractable. On my hard drive is a precious collection of spreadsheets I collected over the last few years while working on my book – some provided by patient and helpful (and transparent! yay government sunshine!) water agency officials across the West, many built myself from old paper documents accumulated over the years. When a water district manager claims a reduction in summer irrigation, I now know where to go for the monthly totals through time to check it out. (Looking at you, Yuma County Water Users Association. And yes, the claim checked out.) But the current state of the data does not make this easy, and there are many, many geographies and categories of water use for which the data do not exist at all.

And even when the data does exist, it’s been collected in a particular way to meet a particular need, and comparisons across regions and water agencies trying to do the sort of apples-to-apples analysis that good regional<->national water policy requires is nigh impossible.

So yes, I’m in agreement with Charles – those of us trying to improve our nation’s water policies need better data to work with.

But I as I sit here in the midst of putting together a lecture for the students next week on the role of science in politics and policymaking, I am less clear than Charles about the direction the data<->policy arrows run.

Researching my book, I spent a lot of time trying to understand the places and the ways in which water governance has succeeded. My favorite example, which I spend a lot of time on in the book, is the West Basin regional aquifer in Southern California, south and west of downtown Los Angeles. (Here is the 628-page pdf of Elinor Ostrom’s PhD thesis on West Basin. Go ahead and read it, I’ll wait. It’s delightful.) There, the evolution of water governance and the provision of good water data went hand in hand. The evolving governance clarifies the need for data, and then better data feeds back into the evolution of better governance.

Simply collecting and providing good data runs the risk of what David Cash et al. call “the loading dock problem“, where science (in this case data) is collected by the sciencers and then handed to the policyers. This, they argue, is less useful than a two-way process in which those who would use the data help define the data that they need, and take ownership of and confidence in the results. What happened in West Basin very much involved the sort of “coproduction” of science Cash and colleagues describe.

Thus I am of a mixed mind about the usefulness of what Charles asks for:

Congress and President Obama should pass updated legislation creating inside the United States Geological Survey a vigorous water data agency with the explicit charge to gather and quickly release water data of every kind — what utilities provide, what fracking companies and strawberry growers use, what comes from rivers and reservoirs, the state of aquifers.

I fear that such a national effort, much as it might simplify my desire to have a better handle on the water consumed by the Colorado River Basin’s alfalfa farmers, is insufficient to spark the revolution Charles hopes for. So maybe call this “necessary but not sufficient”?

Despite drought, California agriculture adds 30,000 jobs

It’s increasingly clear that the lessons we’re learning from California’s drought are not those we expected. Far from the doom of so much of the rhetoric, Californians are adapting to scarcity with remarkable aplomb.

The latest data point, from Phillip Reese and Dale Kasler of the Sacramento Bee, may be the most interesting yet:

California’s farm industry kept growing in 2015 despite a fourth year of drought, adding 30,000 jobs even as farmers idled huge swaths of land because of water shortages.

Preliminary estimates from the state Employment Development Department show farm employment increased by an average 7 percent from 2014.

Reese and Kasler give a good accounting of how this happened, as farmers shifted out of low value crops and into higher value crops that both employ more people and return more crop revenue:

Chris Thornberg, an economist at Beacon Economics in Los Angeles, said the figures indicate the farm industry is exaggerating the effects of the drought on its bottom line. He said the fact that revenues keep growing proves that too much water has been spent on low-value crops such as hay. Take those field crops out of production and it barely touches revenue, and employment keeps growing.

Correction: It might rain in Albuquerque again after all

One of my journalistic tricks has always to pick my moments for grim weather stories – watch the forecast and write when it is at its worst. Because tomorrow the forecast will be different, and I’ll loose my window to write the “It could be the driest/wettest/hottest coldest since X” story. I am not proud, but the incentives are what they are.

Thus I am happy to report that, contrary to what I wrote yesterday, it might rain again in Albuquerque:

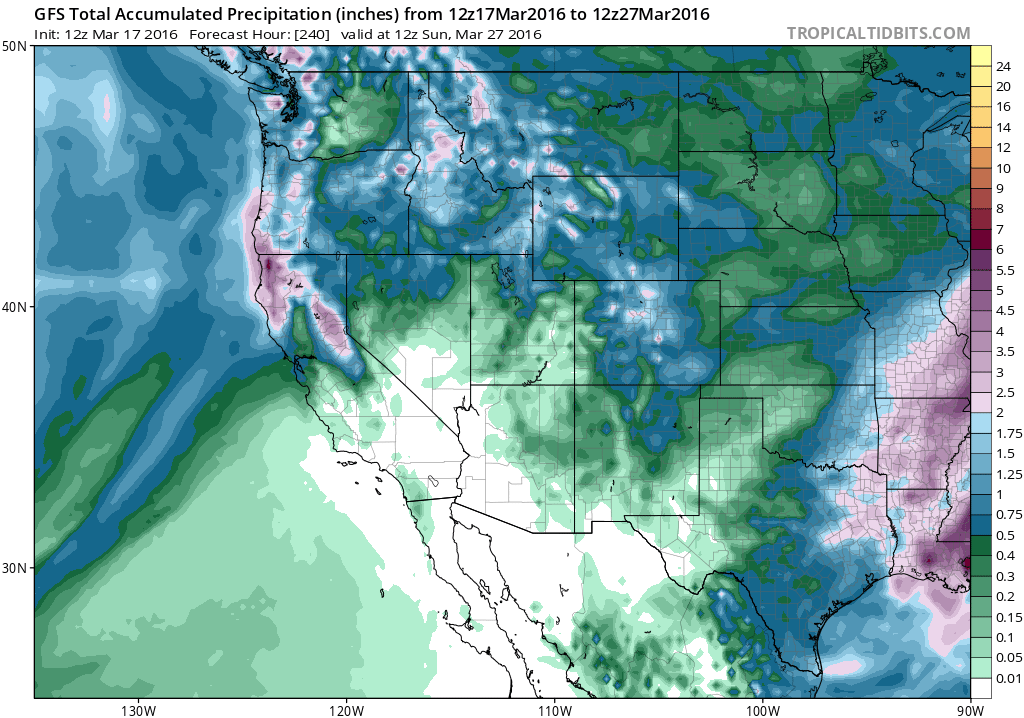

Accumulated precipitation through the end of March. Model by National Centers for Environmental Prediction, graphic by Levi Cowan.

So odds favor wet across the Colorado Basin over the next three months, or so the forecasters say

Fleck’s water news, March 16, 2016

My kindasortaweekly water news is out. Somehow drought shaming in California helped fill Lake Shasta, or something. You should click. Or subscribe for all the goodness delivered direct to your in box. This week’s includes a picture that’s prettier than I realized when I took it:

Colorado River, Black Canyon, by John Fleck

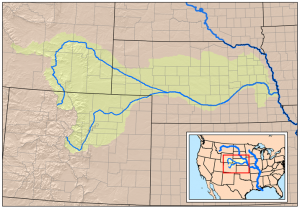

The South Platte-Colorado Basin linkage

Add the South Platte in the state of Colorado to my list of watersheds outside of the Colorado River Basin that I need to pay attention to in order to understand what’s happening inside the Colorado River Basin.

I’ve written here before about the linkage between the Sacramento-San Joaquin River system and the Colorado, because both are key watersheds for Southern California. The Rio Grande, where I live, is another river outside the Colorado Basin that’s integrally connected by human plumbing to what happens inside the Basin. Now a legislative discussion in the state of Colorado suggests a need for similar attention.

The South Platte flows out of the Rockies through the state of Colorado’s urbanizing Front Range communities and across the agricultural plains, providing a key water supply for both. There is a discussion underway now about adding storage on the South Platte, as Marianne Goodland explains in the Colorado Independent:

Millions of gallons of water flow into Nebraska, far exceeding the amount required under the Colorado-Nebraska compact that governs South Platte water use. And Colorado wants and needs to keep that water.

The question lawmakers have to answer now is how to store the water and more importantly, where.

Remember that this is on the other side of the Continental Divide from the Colorado River Basin. But the question of “transmountain diversions” is a hot one in the state of Colorado – should/could more water be taken from west of the divide and shipped across to the east? We already do a lot of this, but there’s pressure to do more.

Goodland’s piece raises this intriguing question – could additional storage on the South Platte increase pressure to move more water out of the Colorado River Basin, because now farms and cities on the eastern side of the divide have more places to put it?

The only opposition to Brown’s bill came from Trout Unlimited’s David Nickum, who said he sympathized with Western Slope residents who fear the water shortfall will require more diversions of mountain water into the Front Range….

The fear of another transmountain diversion prompted concerns from Rep. Diane Mitsch-Bush, a Steamboat Springs Democrat. She proposed an amendment to ensure the study wouldn’t look at mountain water as a way to fill a South Platte reservoir.

We’ve built at artificially vast watershed. I guess I need to start paying attention to water management on the South Platte, too.

One of the driest February-March’s in Albuquerque history

Correction (update?): As of Friday, March 25, 2016, it’s now not likely to rain in March after all.

Correction (update?): It might rain after all!

In 1934, the official Albuquerque weather station received 0.04 inches of rain in February and 0.01 in March.

This year, we received 0.05 in February. So far, we’ve gotten just a trace of precipitation in March. The latest forecast model runs suggest we are likely to get no more.

Weather records before the 1930s for Albuquerque get a bit sketchy. The official tally recorded just a trace of precipitation in February and March of 1902, and there are a few years for which we don’t have complete records. But it’s fair to say that we are on track to have one of the most depressingly dry February-March’s since people began measuring and writing stuff down.

update: I missed 2011 when I wrote this, which was also down in this same cellar, with 0.04 in February and just a trace in March.

Hitting “send” on my book’s manuscript, again

There’s no way to pin down the moment I started working on my book, because it happened in fits and starts that extend back in one form or another for more than a decade. But the first time I really went all in was in the spring of 2010, when I made a trip down to Yuma and then up the Colorado River over several days to Las Vegas. It was the first time I went beyond just saying I was working on a book and actually spent money on fast food and cheap motels.

There was still sunlight left when I dumped my stuff at the motel, so I did what I always do, wherever I go. I went down to the river. Below and to the right of where this old railroad bridge used to cross the Colorado, the good folks of Yuma have built a fine city park, and on that April Sunday it was hopping. I got the last space in the parking lot, most every picnic table was in use, the barbecue grills were fired up, there were tubers in the river.

I asked the first person I ran into whether there was a community festival or something going on. Why all the people? No festival, she told me. Just a nice Sunday at the river.

At that moment I bonded with Yuma, a community that in many ways for me captures the 21st century Colorado River. It’s a desert farm town, with all the dry and hot and poor that goes along with that. But more than any town as you head up the Colorado River until perhaps Moab in Utah, Yuma has embraced its river. Most of the West we built around the Colorado River has required moving water out of the Colorado River and using it elsewhere. And in fact Yuma does that too. Most of the Yuma County ag water is diverted 20 miles upriver at Imperial Dam. But Yuma emphatically remembers that it’s a river town. The network of canals that brings the water down is a marvel all its own.

But Yuma remembers the river at its heart, too. Last year I was there again on Easter, pulled in at dusk to the Hilton Garden Inn overlooking the park, and it was the same scene. The light was fading (it was darker than this picture looks, thank you Adobe photo modification products), but the people were still out at their river.

This is part of what motivates the project that my book turned into. I started the effort with a dismissive bias against desert agriculture. Does it make sense to grow alfalfa in the desert? By many measures, the water is more valuable in other uses. The economic benefits of urban water use dwarf those of desert agriculture, while at the same time environmental values press in from the other direction. But I’m unwilling to tell these folks, “Sorry, not enough water, we need it elsewhere.” I believe there is an alternative.

In the book I document three basic trends:

- farm communities like Yuma, growing their agricultural economies while using less water

- cities like Los Angeles and Las Vegas, growing their economies while using less water

- the growth of institutions needed to capitalize on those trends and develop the next level of water allocation and sharing rules to thread the needle left us by drought and climate change

There’s a fourth trend that’s not so clear, but about which I choose to be optimistic – a shift toward returning some water for the environment. In the book, I lay out an argument for how the institutions of that third bullet can leverage the first two. I am optimistic. I think we can do this.

I sent off the final copy-edited version of the book to the fine folks at Island Press this afternoon. There’s still one more wave of editing to come, proofing galleys in a couple of months. On the shelves, I hope, by September. Dying to share it with y’all. Soon.