I’ll be at the Nevada Water Resources Association meeting in Las Vegas next week, talking Wednesday morning about what we need to do to avoid running out of water. If you’re there, say “hi”.

Does Pasadena, Calif., need more water?

Pasadena, a suburb of Los Angeles, is in the hunt for more water:

A recycled water project started in 1993 moved forward Monday night as the Pasadena City Council approved the environmental review of a plan to funnel water from Glendale.

The $50 million project could take 20 years to complete, with a pipeline running from a proposed reservoir in Scholl Canyon in Glendale to one at Sheldon Reservoir near the Brookside Golf Course. It would increase Pasadena’s local water supply by about 10 percent, officials said.

Pasadena, part of one of the earliest California efforts to regulate groundwater pumping, gets more than half its water from Metropolitan Water District imports, water from Northern California via the State Water Project and the Colorado River. The rest coming from the local groundwater basins. It’s always been of interest to me because it’s where I started writing about water in the late 1980s, as a newspaper reporter for the Pasadena Star-News.

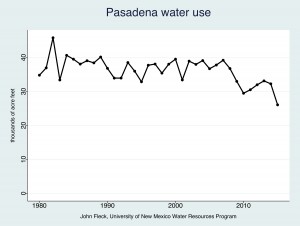

When Emily Green this morning linked to Jason Henry’s story on the new Pasadena water plan, it prompted me to pull the latest data on the community’s water use. The results are unsurprising. Like nearly every community I look at, water use is down.

Since we left 25 years ago, Pasadena’s population has risen 10 percent. Its total water use has declined 29 percent. Per capita use is down 35 percent. Water use in 2015 was by far the lowest in the 35 years for which I have data.

This graph represents total water use, the combination of local groundwater and imported supply from Met.

You can see the big drop in 2015, as Southern California water users respond to the drought-tinged regional conservation initiatives. But even before that, Pasadena was part of the overall trend toward reduced water use in the metropolitan western United States.

Everyone’s using less water.

Will Utah take more water from the Colorado River Basin?

Sarah Tory at High Country News has a nice summary of one of those classic western water issues worth watching – the Lake Powell Pipeline proposal:

The project would pump 86,000 acre-feet of water from Lake Powell 140 miles across the desert through a 69-inch buried pipe and then 2,000 feet up and over the mountains into the Sand Hollow Reservoir, 13 miles west of St. George.

For nearly a decade, the pipeline has provoked intense debate, pitting two visions of water management against each other. On one side are those who think the project is not only an outdated solution to water needs, but unnecessary. On the other are those who believe the pipeline is an essential part of addressing southwestern Utah’s future growth.

I’ve been thinking of this as one of the West’s “zombie projects”, relics of a past approach to water management that won’t move forward because of the reality of its enormous cost relative to the amount of water it would provide, and the steady reductions in per capita water use pretty much everywhere. But it keeps inching forward. I could be wrong about zombies.

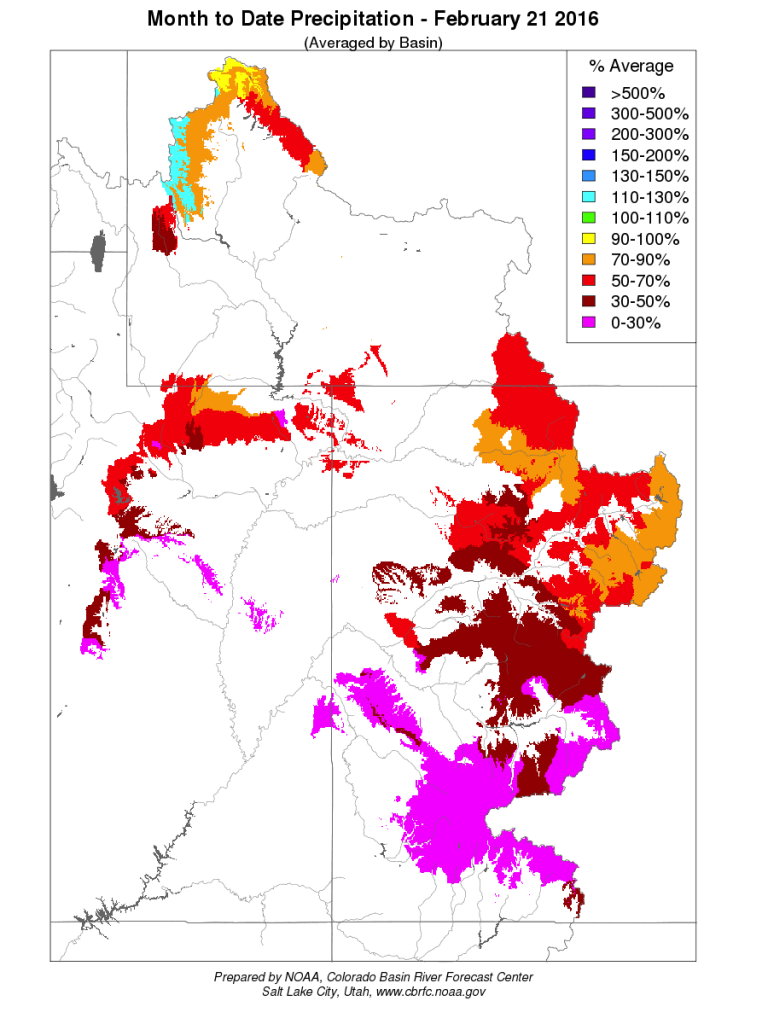

A bad February in the Colorado River Basin

The Sacramento Delta-Colorado River farming nexus

I was talking the other day about California’s struggle to solve its Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta problems with a friend who grows food with Colorado River water in California’s southeastern desert. The delta’s more than five hundred miles and three or four watersheds away as the crow flies from his farm. Why such a keen interest?

Here’s the map. My friend’s farm is near the Colorado River in the appropriately colored brown blob down in the bottom right corner. The Sacramento Delta is in the green bit in the center left, near the coast.

The problem lies in the political geography of California water. The Los Angeles-San Diego metro area (the lower green coastal blob on the map) gets large supplies of imported water from both places – the Sacramento Delta and the Colorado River. To the extent that supplies from one of those two places become smaller or less reliable, it places enormous pressure on Southern California to trade that problem off against increased supply and/or reliability from the other. (Both variables, supply size and reliability, are crucial.)

The Sacramento Delta is a mess, both in the plain English sense of the word (“a state of affairs that is confused or full of difficulties”) and in the more subtle framework of Berkeley policy scholar Emery Roe in which policy messes are things not to be cleaned up so much as managed. The Sacramento Delta mess involves a plumbing system that needs to pump vast quantities of water through an ad hoc network of old sloughs and channels ill-suited to the task, completely rejiggering the natural and human environment in a way that creates all sorts of reliability problems along conflicting dimensions – distant human water needs, local human water needs, environmental water needs, local and distant cultural values and needs. Building the big plumbing systems of the 20th century has created interconnections across social and governance boundaries that our 21st century institutions remain poorly equipped to handle.

AroundDeltaWaterGo

One proposed solution is to build ginormous tunnels beneath the damn thing, bypassing the water. California keeps changing the name of this project – it was once a Peripheral Canal rather than a tunnel system, it was the Bay-Delta Conservation Plan, I tried to name it Peripheral Thingie but failed, it’s now California WaterFix, my favorite new name is OtPR’s AroundDeltaWaterGo. More importantly, California keeps not quite deciding to build it, but also not deciding to not build it.

Water behind Imperial Dam is currently headed for desert farms. But will L.A. need it? photo by John Fleck

I am agnostic about whether AroundDeltaWaterGo is a good idea or not. I haven’t spent the time to form an informed opinion (do jump into the comments and explain what an idiot I am for not seeing the obvious merits of your argument for/against). But sitting out here in the Colorado River Basin I am acutely aware of the regional implications of how California handles this mess.

Jeff Kightlinger, head of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, has been on a public tear lately arguing the merits of the tunnel scheme:

California WaterFix proposes to build three new intakes in the northern Delta that are outside of the typical migrating range of adult delta smelt. The intakes since January could have been capturing as much as 9,000 cubic feet per second of supplies in addition to what we have been diverting from the existing south Delta facilities.

How much water are we talking about? Every day we cannot capture 9,000 cfs in supplies because we don’t have California WaterFix on line, the lost supply is roughly six times the daily demands of the cities of Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco combined.

To the extent that Met can’t grab that water from Northern California, it increases the pressure to look elsewhere. And my farmer friend and his neighbors in the agricultural communities of the deserts of southeastern California – the Imperial Irrigation District, Bard, the Palo Verde Irrigation District – are that “elsewhere”. The ag districts have Colorado River water rights, and Met has an aqueduct that could bring some of that water to the vast metro areas of the coast.

Met right now looks like it has to play a zero sum game. I can see why a farmer in California’s eastern deserts might have some enthusiasm for construction of giant tunnels 500 miles away that will bring him zero water.

Water insecurity: think poverty, not climate

I’ve recently become acquainted with interesting research by Texas A&M geographer Wendy Jepson, who has studied household water insecurity along the U.S.-Mexico border. There’s a tendency to look for a technological fix (“Look at this cool new filter we invented!”), but Jepson found this less than effective (“HWS” is “household water security”):

We evaluated the efficacy of a novel water engineering technology (point-of-use water purification system) designed to improve access to potable water. We used the HWS metric to argue that these devices exacerbate water insecurity in some cases because they increase risk of household water contamination and require more money, time, skill, and labor to adopt and maintain that other forms of water provision. These “mediating” devices not only mask the slow violence of chronic water insecurity behind technological hubris, they undermine colonias residents’ vision of themselves as political actors in water governance.

And I said “poverty” in the post’s headline, because that’s an obvious variable in this. The poor communities along the U.S.-Mexico border, (like East Porterville in California or the Navajo Nation here in New Mexico) are more likely to face water insecurity. But Jepson’s work points to an important nuance:

The HWS security metric also allowed us to run binary and ordered regression models to determine what demographic characteristics are likely to result in household water insecurity. Surprisingly, our study determined that immigration status of households not household income was the most significant predictor of water insecurity. (emphasis in original)

What does it mean to have “drought” in Yuma?

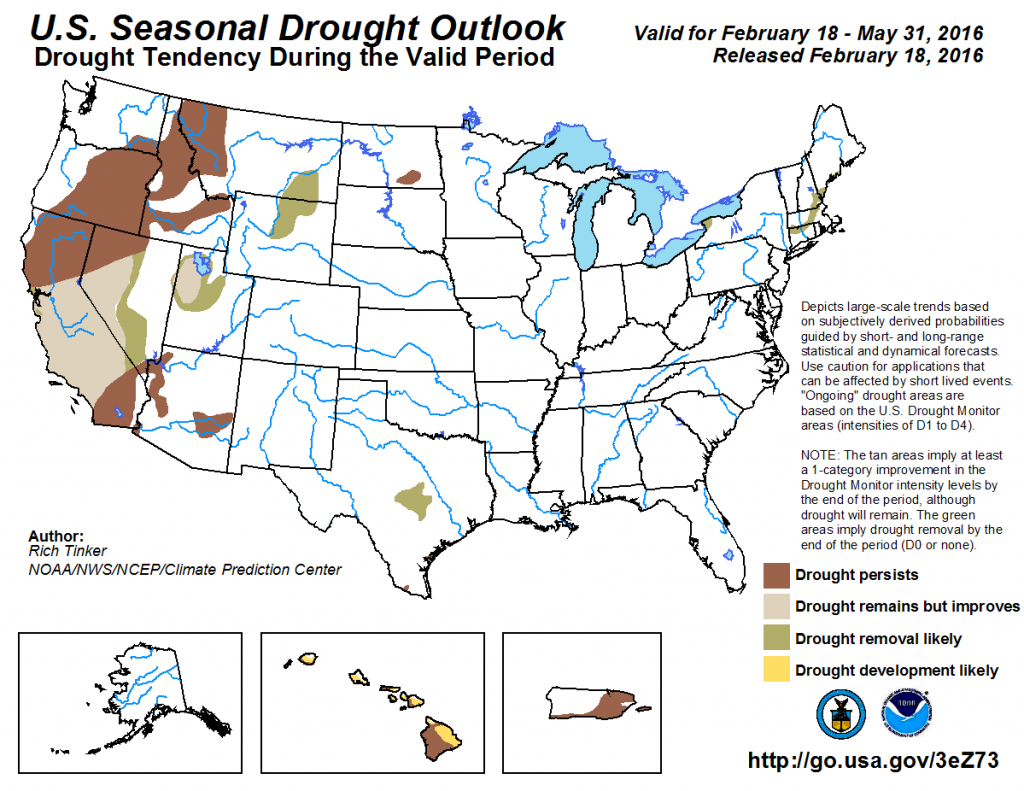

In my endless puzzling over the meanings we attach to the word “drought”, there is this, from yesterday’s Climate Prediction Center seasonal drought outlook:

What does it mean to talk about “drought” in places like Yuma or the Imperial Valley that average less than 4 inches (10 cm) of rain a year, and that get all their human-meaningful water from someplace else?

On the Colorado River, the environment is the junior user

Members of the Colorado River Research Group, scholars who study the basin, have a useful new report out today (pdf here) urging a more unified approach to the currently fragmented environmental management initiatives on the Colorado River. It describes “an incomplete patchwork of largely uncoordinated efforts, existing in some cases to facilitate compliance with environmental laws that might otherwise constrain users from withdrawing additional water from the river system.”

In other words, the driver isn’t really the environment, so much as managing the problem of environmental values getting in the way of taking water out of the river. This is where the strange accretions of our water management law have left us.

At the heart of current Colorado River management are laws, policies, dams, and aqueducts that divide the flow of the river into many discrete allocations and rights. The current strategy is politically motivated by the desire to minimize interstate and binational competition for limited watersupplies, while simultaneously empowering states and local water managers with the legal certainty and autonomy necessary to support the management of their water allocation. Environmental programs evolved later around this pre?existing framework, with most efforts focused on modifying the operations, or mitigating the impacts, of the basin’s physical infrastructure. An unintended result is a framework that often impedes the search for coordinated management strategies.

The key takeaway message from the “Law of the Colorado River” conference I attended a couple of weeks ago in Las Vegas: it sucks to be the junior user on an over-appropriated river system. Under the doctrine of prior appropriation, the guiding principle for western U.S. water management, “senior” water uses/users – those that have been extracting water the longest, have the highest priority when water gets scarce. Those are usually farms. “Juniors” – those who came later, primarily cities – have a share that is generally smaller, and that is at greater risk as supplies run short.

In California, for example, the Metropolitan Water District, which has a smaller share of water that is also junior to the big farm districts of Palo Verde and Imperial. Met is rich and politically powerful, but this is one of the great examples of how water doesn’t simply flow uphill toward that money. It sucks right now to be Met.

Arizona is junior in a bigger way, because the cities of central Arizona came to the party even later, so they’re junior to all of California’s uses.

A lot of the jockeying right now involves coming to terms with that problem.

But the CRRG report is a reminder that the environment is the ultimate junior.

Awaiting our May miracle in the Colorado River Basin

It was 72F (22C) in Albuquerque yesterday, a record, and our decent snowpack is already starting to melt out. It’s early for that. And February (see PRISM map at right) has been dry, which hasn’t helped.

In the Upper Colorado River Basin, snowpack measured across all the river’s main tributary systems above Lake Powell (the Upper Colorado itself and the Green) is just 92 percent of average, according to the CBRFC. The mid-February forecast for total runoff this year into Powell is just 90 percent.

And yet, if you’ll permit me to mix anecdote with my data….

We had a visit yesterday evening from our friend Nancy, who used to live around the corner and recently moved to Pagosa Springs in southern Colorado. She’s learning to live with four feet of snow, and the neighbors tell her it’s the most they’ve seen in a while. The latest forecast on the Rio Blanco, which is the nearest measurement point to Nancy’s new house, is 10 percent above average. Importantly for us, that’s one of the key tributaries that supplies San Juan-Chama Project water to Albuquerque.

And the new seasonal forecast from the Climate Prediction Center for March-April-May, out this morning, is promising:

Why did Flint happen?

We’ve got a ton of hero/villain narratives underway around the water contamination problems of Flint, Michigan. But there’s always a risk of post hoc storytelling here. As storytelling beings, we gravitate to narratives like that. But inevitably the heroes and villains are embedded in deeper institutional structures that are a necessary precursor to the problem, and fixing problems like this, broadly, requires fixing the conditions that allow this villainy to exist and require this heroism to fix it.

This is one of the important insights of the “solutions journalism” movement, and this is precisely what I love about the work Laura Bliss at Citylab, including this piece on Flint and the problems of places like it:

One crucial concept is environmental federalism, the basic enforcement structure underlying America’s big environmental protection laws. The federal government sets environmental standards, such as the Safe Drinking Water Act. States are the “primacy agencies” charged with implementing and enforcing those standards on a local level. Local governments and public water districts are supposed to comply with the state (and, by extension, the feds).

But environmental federalism creates some common trip-ups. First of all, “local and state politics always affect compliance,” says Teodoro. Local governments might determine that the cost of complying with federal and state standards is simply too high, too burdensome, or too politically onerous. For instance, compliance might require raising water rates, a risky move for local leaders seeking reelection. Or maybe the local population served by the water agency is politically marginalized, and thus deemed unworthy of the funding necessary for compliance.

Bliss is explicit in not excusing Flint’s villains. But her work shows why it’s important to go one step beyond and look at the institutional structures that push things in Flint’s direction.