The Pacific Institute and others have published a useful new study on “Incentive-based Instruments for Freshwater Management” which raises some interesting issues about the language we use to describe water policy instruments.

The farm district in Bard, California, is negotiating with urban water users to fallow cover crops like this and send conserved water to the city

Deep in Abrahm Lustgarten’s excellent new piece about water markets in the West is this description of the arrangement by which the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California pays farmers in Palo Verde (the deserts east of Los Angeles) to fallow fields so that water can be transferred for municipal use in coastal Southern California:

The arrangement is anything but a free market: To ensure that most of the water stays in the valley, the agreement limits the amount of land any one farmer can fallow in a year to 35 percent of his or her holdings. Still, farmers get added income without losing their rights to the water, and the Metropolitan Water District says Los Angeles and its other cities get reliable access to water, which helps them make it through drought years.

The distinction here is between “free market” and more regulatory approaches that specify in law who gets how much and for what, but I think what’s happening in Palo Verde has important market characteristics that matter. I think we’ve been getting wrapped around our axle in trying to fit this square peg into the round “water markets” hole. These things will never be like buying and selling oil. Water, as the Pacific Institute study notes, has a lot of characteristics that make normal markety stuff impossible:

It is heavy, unwieldy, and easily contaminated; it sometimes has dramatic seasonal and year-to-year variability; and it can be easily lost through evaporation, seepage, or runoff…. Further, these externalities may be borne by disparate parties, such as the environment or future generations, challenging efforts to compensate those injured by trading.

One of the points Robert Reich makes in his new book is that markets are at root institutions created by political systems, so by design if you do build a “water market” you end up with institutional arrangements that either do or don’t take the problem stuff into account.

Institutional arrangements are among the most important factors that determine the ultimate success or failure of water trading. Successful water trading requires secure and flexible water rights that recognize and protect users and others from externalities.

When we talk about “markets” in all this, the generic language prejudices us toward a specific notion of freeness of buying and selling, but really these things are always bound up with incredible institutional constraints that make very few of them look like buying and selling hog bellies*. That’s why I really like Cohen et al.’s language of “incentives” instead. It allows for a lot of the characteristics many people like about markety stuff, but allows for a lot of the kind of boundaries and constraints that Lustgarten argues make it “anything but a free market”.

Yes. Exactly.

Which brings us to Bard, the little irrigation district across the Colorado River from Yuma, in the far southeastern corner of California.

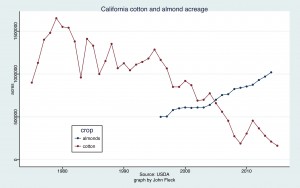

The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and the Bard Water District last month launched into a new arrangement in which Bard farmers can be compensated for fallowing fields during the hot late spring and summer months. Bard farmers do a lot of winter lettuce, for which they make a lot of money. Then, as is common for the winter lettuce trade, they plant the land in a cover crop – maybe cotton or sudan grass or something – that makes a lot less money. Negotiations are now underway on deals in which Met would compensate farmers $400 an acre to fallow instead during those months.

This has a lot of the characteristics of a market – willing buyers and sellers who have negotiated a price. But it is anything but a free market. There are a lot of constraints – limits on total acres involved, and it only applies to fallowing and water transfer during a few months of the year. Those are constraints intended to manage the externalities – keep agricultural land in production, protecting community of origin values.

I really like the language of “incentives” rather than “markets” here. It gets us past a hurdle that has hampered the conversation.

* I got “hog bellies” into a blog post. Achievement unlocked.