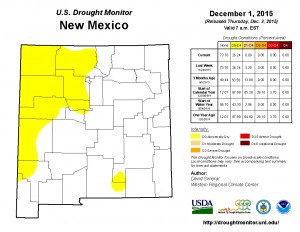

For the first time since Nov. 30, 2010, New Mexico has been categorized as entirely free of “drought” in this morning’s federal Drought Monitor. 26 percent of the state remains “abnormally dry”, but none of the state is in any of the monitor’s formally designated drought categories.

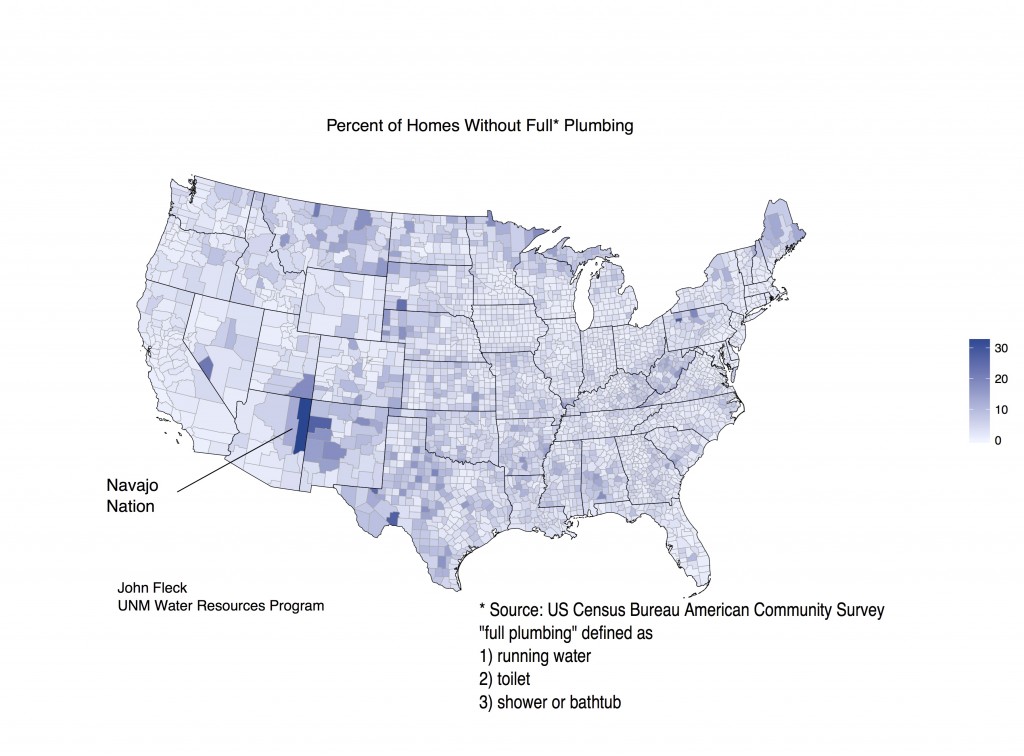

This does not mean that we are free of the sort of problem that one might normally label as “drought”, because it is a word with no one meaning, which is one of its difficulties. It depends entirely on how you use and perceive your need for water. If you are a farmer dependent on snowpack and reservoir storage to water your Hatch chiles, “drought” is not over. If you are a piñon in the low mountains of northern New Mexico sapped of soil moisture by warming temperatures, “drought” may never be over. If you are me, sitting in Albuquerque with a full reservoir of banked water upstream, a backup supply of groundwater in an aquifer that has been rising despite a long term precipitation deficit, and water demand that continues dropping because of conservation success and population growth that has nearly stopped because of a tanked economy, “drought” may be an increasingly unhelpful conceptual category.

Defining drought’s end

Some good numbers:

- The Albuquerque National Weather Service gauge has received 10.5 inches of precipitation in 2015 to date, 17 percent above the long term mean.

- The aquifer at Jerry Cline Park, near my house, has risen 18 feet since the winter of 2008, which is the turning point for Albuquerque groundwater management.

- Flow on the Rio Grande through Albuquerque this morning is 1,830 cubic feet per second, more than double the mean for this date.

Some bad numbers

- Elephant Butte Reservoir remains extremely low, at 11.5 percent of capacity. This is the reservoir that serves the most economically productive farmland in New Mexico.

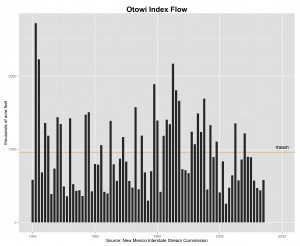

- Since 2000, we have had just two years of above-average flow in the Rio Grande.

- The average temperature in the state’s forested northern mountains in 2010 has been 2.5F above the long term average. The last year that was below the long term average (as measured by a bit more than a century of records) was 1991.