Mount Holyoke’s “Academic Minute” has a nice interview with Park Williams, who’s been using tree rings to flesh out the story of the current drought in the context of historic droughts, as it pertains to forests in the Southwest:

I study the year-by-year records left by these rings, and they tell a fascinating story more than a thousand years long, about life in a water-limited world. One of the most interesting chapters is a five-hundred year stretch ending in 1300 AD, when the Southwest was ravaged by a series of prolonged droughts. Climate scientists call them “megadroughts.”

Each megadrought lasted longer than a decade, and probably contributed to the abandonment of ancient cliff-dwelling cities such as Mesa Verde, in Colorado.

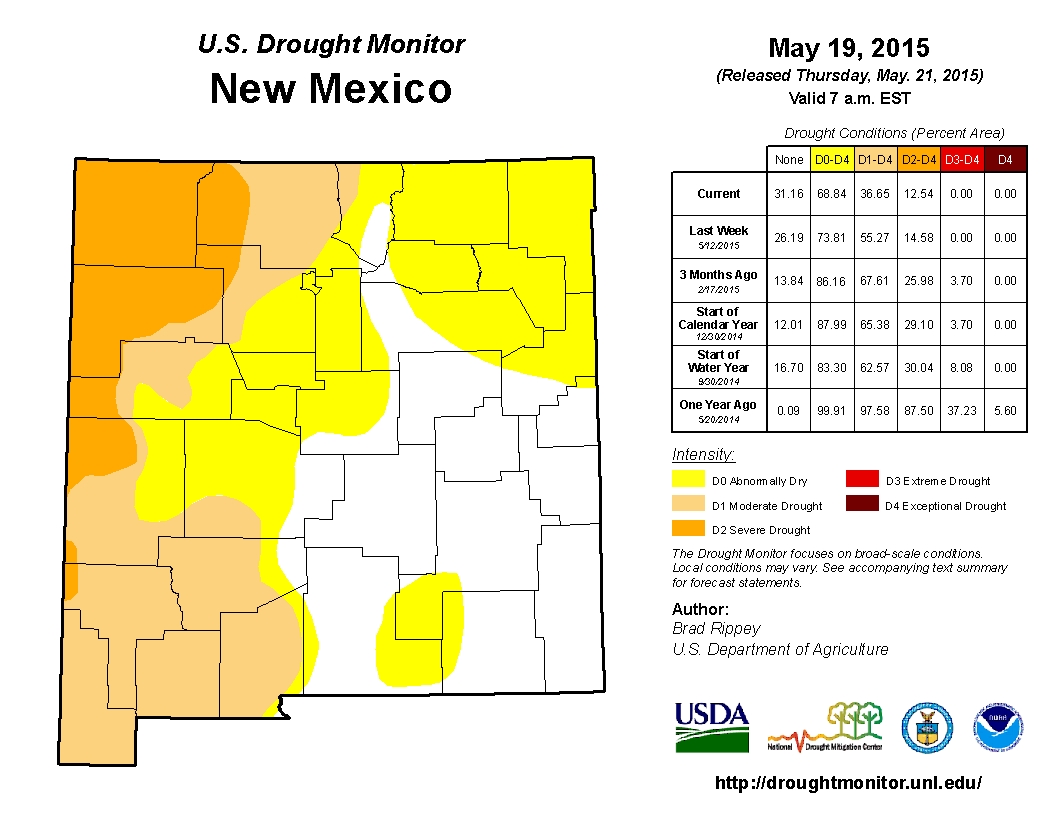

Currently, the Southwest is entrenched in a 15-year drought. Tree rings and climate data suggest that this ongoing drought is on par with some of the worst megadroughts of the past millennium.

Click through to listen to audio of Park telling the story himself. And just FYI, if you think this stuff is interesting and want to share it with a youngster you know, I wrote a book a few years back called The Tree Rings’ Tale for middle school-aged kids.