.

.

great blue heron, Rio Grande Bosque, Albuquerque, New Mexico, December 2019

The first bird I formally identified, as in “sat down with the book and then wrote down the result” was a great blue heron.

The entry in the old family Peterson Field Guide to Western Birds, red ball point pen:

11/86 Sat on tiny island in Colorado River all morning, picking at its feathers

The book dates to the 1960s. Per the inscription in the front, it was a Christmas 1968 gift from my father to my mother. When Lissa and I were married it was passed down to us.

I cannot remember the November 1986 Colorado River blue heron campground with precision. It was on the Lower Colorado, the Blythe stretch I think (North of Blythe? South?) on the Arizona side, I think. There were a few tent spaces, but it was mostly RV’s. We were poor, and tent campers, and went often in the winter months from our home in South Pasadena to the deserts of the Lower Colorado.

When I was young and imagined being a writer (which is almost certainly what I was imagining on that trip in November of 1986 as I sat looking out at that river), I had a character in mind who lived in the desert – out near Joshua Tree, in a mobile home – and learned the names of birds. The naming of things has always seemed important to me:

And out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.

The heron, if you believe in such things, has always been a spirit animal for me, following me on my travels. One swooped up into a cottonwood this morning as my friend Scot and I were riding our bikes up through the woods along the Rio Grande, kindly posing, that I might take their picture and remember their name.

New Mexico has dithered long enough in its efforts to build a federally funded Gila River diversion, Interior Assistant Secretary Tim Petty said in a letter to state officials today:

Feds say “no” to Gila project

Bret Jaspers at public radio station KJZZ in Phoenix did a two-part piece starting with a nice overview of our new book, followed by a good dive, from the Arizona perspective, into the options we have for extricating ourselves from the Colorado River’s overallocation problems.

I returned to a message I’ve been hammering on regarding what’s going on in Arizona right now:

“In 1968 when the Central Arizona Project was approved, Arizona knew that there was not sufficient water to keep that canal full year in and year out,” Fleck said.

He points to testimony from then-Reclamation Commissioner Floyd Dominy, who told a House of Representatives subcommittee that “sooner or later, and mostly sooner, the natural flows of the Colorado River will not be sufficient to meet water demands, either in the lower basin or the upper basin, if these great regions of the Nation are to maintain their established economies and realize their growth potential.”

Fleck said Arizona knew that without augmentation, the water available for CAP canal customers would fluctuate.

“And somehow that was forgotten, and Arizona grew to depend on a full CAP canal every year,” Fleck said.

As John Berggren pointed out when I pushed on the same point last summer at a conference in Boulder, banging on this point may not be helpful at this point. Arizona did what it did over the last half century, and is where it is now, mistake or not.

It’s hard to disagree with him on this, but I still keep saying it.

I could see the reporters at last week’s Colorado River Water Users Association meeting chafing at the rhetoric we were hearing regarding climate change. In my strange new role (kind of a reporter, I am writing another book, and kind of not – I have this crazy university gig) I was invited into the news events, but tried to hang at the metaphorical back, letting the folks with daily deadlines and immediate needs ask most of the questions.

And regarding climate change, ask they did. Here’s how the Arizona Republic’s Ian James characterized the scene as he explained the comments made by Interior Secretary David Bernhardt:

He didn’t mention the words climate change during his speech at the conference. But during a press conference afterward, reporters asked Bernhardt about the role of climate change.

“I certainly believe the climate is changing,” Bernhardt said. “I spend a lot of time with our scientists, and I spend a lot of time with our models. And you know, what the scientists tell me is that the best thing we can do is make sure that if we’re using a model, we use multiple models and multiple ranges within each model. And so that’s what I’ve insisted on when we’re looking forward to the future.”

In projecting the river’s flows into the future, he said, “we absolutely follow best practices all the time.”

After Bernhardt’s news “gaggle”, I put on my university professor hat, echoing in part an argument I’ve been hearing articulated with increasing clarity by Brad Udall:

John Fleck, director of the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources Program, said Bernhardt’s comments reflect a dichotomy within the federal government in which officials are taking steps on climate adaptation but not on combating planet-warming emissions.

On the one hand, water managers at the Bureau of Reclamation are working with scientists and using climate models to assess risks and project the river flows into the future, Fleck said.

“They’re absolutely taking climate change seriously. It’s built into the modeling work they’re doing,” Fleck said. “You don’t find water managers doubting the reality of human-caused climate change and its effects. They’re seeing it in the flow in their systems, and they’re dealing with it.”

On the other hand, he said, there is a “disconnect” in that the Trump administration isn’t taking steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

“So that increases our risk,” Fleck said. “That’s a problem because we need to reduce greenhouse gases to mitigate the effects on the Colorado River.”

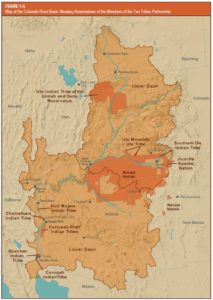

One of the central themes of last week’s Colorado River Water Users Association annual meeting was the was the role of the basin’s Native American Tribes in the many decisions that will guide and manage water use on the Colorado River over the next several decades (for example, the post-2026 Guidelines). CRWUA attendees heard a report on the Water and Tribes Initiative co-facilitated by Matt McKinney and Daryl Vigil.

Tribal Water Study

Tribal Water StudyWhile our book, Science Be Dammed, is primarily about the science (hydrology) of the river – What did we know, when did we know it, and how did we use it? – the research John Fleck and I did has given us some interesting insights on the how the basin states and federal agencies that dominated the development of the river viewed the water needs and rights of the Tribes.

Those familiar with the Law of the River know that the 1922 Colorado River Compact addressed the Indian questions with a single sentence. Article VII states “nothing in the compact shall be construed as affecting the obligations of the United States of America to Indian Tribes.” The provision was put in the compact at the insistence of Chairman Hoover. His original suggested language was “nothing in the compact shall be construed as affecting the rights of Indian tribes.” The minutes give scant reason for the language change that Hoover himself suggested. (Hundley, Water and the West, pages 211-12).

Based on the compact minutes and Hoover’s 1923 report to Congress, he considered the federal obligations to Indians as similar to future treaty obligations with Mexico. He considered both as core federal interests. Before the compact negotiations began, Mexico requested that it be formally represented on the commission. At the request of the State Department, Hoover responded that the compact was solely a domestic matter, but Mexico need not worry. Its rights could be determined by a treaty and “such treaty rights” he noted “will override interstate arrangements” (Hundley pages 175-6). During the negotiations Hoover cautions that without Article VII, Congress would include a reservation to protect tribal rights under treaties (Minutes of the 21st Meeting). In his analysis of the compact for Congress he notes that the provision disclaims “any intention of affecting the performance of any obligations owing by the United States to Indians” and “it is presumed the that the States have no power to disturb these relations” (The Colorado River Compact: Analysis by Herbert Hoover, January 30, 1923, answer to question #24).

In Water and the West, Hundley is critical of the commission, concluding that “no attempt was made to discover how many Indians were in the basin and what their water needs were. The Commission simply assumed that the water rights of Indians were ‘negligible'” (pages 211-12). Here, as with our message in Science Be Dammed, reality is more complicated. While there is no reason to disagree that the commission assumed the rights were negligible, the available technical reports suggest that, at least in the Lower Basin, the future needs of Indian tribes were well recognized and far from negligible. The 1922 Fall-Davis Report, the Reclamation Service report that shaped both the compact and the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act, identifies over 140,000 acres of tribal lands adjacent to the river below Hoover Dam that could be irrigated, including the Colorado River Indian Tribes and Ft. Mojave Projects, very similar to the Indian rights that were finally adjudicated in Arizona v. California.

The conclusion of the recently completed Tribal Water Study that the water rights of the tribes exceed 2.9 million acre-feet might have surprised some, but it should not have. By 1944, when the Bureau of Reclamation’s comprehensive report on the development of the Colorado River was being finalized, the Bureau of Indian Affairs identified existing and future Indian projects that would divert (not consume) over three million acre-feet per year of water, including over 800,000 acre-feet in New Mexico (Proceedings of the Committee of 14/16, November 10-11, 1944). Because it acknowledged that Indian rights would be “superior” to non-Indian rights, the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact Commission gave New Mexico an 11.25% share of the Upper Basin’s apportionment (New Mexico provides <2% of the river’s yield) so that it would be large enough to cover the future needs of its Native and non-Native Americans.

For most attendees, the convention’s attention to the basin’s Tribal needs was a welcome and perhaps overdue step. The message I heard was that the basin’s Native American communities are fully engaged and expect that they will be given the opportunity to meaningfully participate in the decision-making processes that will shape the future of the Colorado River. In his remarks, Secretary Bernhardt appeared to offer them a seat at the table. Even so, history suggests, they will still have many challenges ahead of them.

The Boulder Canyon Project Act, carved in stone

Touring Hoover Dam Friday afternoon, a friend deeply embedded in the “Law of the River” asked if I knew that Section One of the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act was carved in stone on one of the Dam’s iconic towers:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That for the purpose of controlling the floods, improving navigation and regulating the flow of the Colorado River, providing for storage and for the delivery of the stored waters thereof for reclamation of public lands and other beneficial uses exclusively within the United States, and for the generation of electrical energy as a means of making the project herein authorized a self-supporting and financially solvent undertaking, the Secretary of the Interior, subject to the terms of the Colorado River compact hereinafter mentioned, is hereby authorized to construct, operate, and maintain a dam and incidental works in the main stream of the Colorado River at Black Canyon or Boulder Canyon…. (emphasis added)

The carving (or maybe it’s cast concrete? further research needed) sits atop the Nevada side elevator tower, and as we were finishing our tour, we lingered on top of the dam, thinking about the implications.

I apologize for the picture. The light wasn’t great. I tried going back early Saturday morning, hoping sunrise light would highlight it better, but alas I think I need to return in spring or summer, when the rising sun might cast the shadows that would better highlight this institution carved in stone. (I do not view a need to return to Hoover Dam as a problem.)

I’ve got a couple of working titles for the next book on which I’m starting to work. “The Ghost of Water” has been my go-to in the last few months as I begin to sketch out the ideas, but as I toured the dam with old Colorado River friends Friday I added one to the mix: “Hoover Down“.

The idea is that we create institutions, and then those institutions shape the land. In between institutions and land sits Hoover Dam.

By “institutions” here I mean not government agencies, but the more expansive definition we teach University of New Mexico Water Resource Program students:

Institutions – the rules of the game, both formal and informal, that both liberate and constrain behaviors in repeated interactions

It’s wonky language, and it took me a while to get my head around the distinction between this expansive definition and the more traditional “institution = government agency” idea. At Hoover Dam, the institution in question is in significant part the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928. (The more traditional idea of what people mean when they talk about institutions, the Bureau of Reclamation, is in this case the tool we use to carry out the rules written down by Congress in 1928.)

In retrospect, there’s a thread in the three books I’ve written that leads in this direction:

During our tour Friday, the kind folks at the Bureau of Reclamation took a group of us down on the power plant floor, where in our post-9/11 world tourist tours no longer go. Standing amid the massive generators on the Arizona side, it was weirdly quiet. There was very little water flowing through Hoover Dam. Why?

friends with the keys gave us a tour of the place

Part of the reason is the changing nature of the power grid. Hydroelectric power plays an increasing role in filling in behind renewable resources when they go off line, so Hoover’s generators tend to ramp up when the sun sets in California.

But part of the reason involves the shifting nature of water management uses and rules downstream. There is simply less water moving through the dam than there used to be. The complex tangle of rules – institutions – is successfully encouraging folks downstream to bank their water in Lake Mead rather than taking it out and spreading it across the land.

Mexico’s water agency notified the U.S. government that it wanted to cut its releases this month and store water in Mead, something that would have been impossible under the rules ten years ago. As I’ve written before, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California will take less water out of Mead in 2019 than it has in any year since the 1950s.

The result is that the Bureau’s current operating plan calls for releasing just 225,000 acre feet of water from Lake Mead in December 2019. I went back through a decade of USBR records (more research clearly needed, this is fascinating!) and that is by far the lowest December release I found.

The idea behind “Hoover Down” is that the dam acts as a funnel that translates rules into moving water. Downstream, that water spreads out across the landscape. As the rules change, the volume of water flowing through the dam changes, and the landscape from Hoover down – not just the river corridor itself, but all the places beyond that use its water – changes as well.

There are a lot of places I could tell this story. I’m thinking about “Hoover Down” in significant part because of my love for that part of the Colorado River Basin – the basin of my childhood.

Friday’s tour was a coda to last week’s meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association. Rules were the primary focus of the discussion, and a part of the work for “Hoover Down” will involve a close examination of the work over the next “n” years on a new, or newly revised, set of rules for how much water enters and leaves Lake Mead. The value of “n” itself is an interesting uncertainty in the whole thing. This book may take a while.

It was a “no big news” CRWUA, the kind where I was glad I wasn’t a beat reporter any more having to gin up a quick story. Ian James (who also joined the tour) turned a nice daily that focused on the key element. Rather than quickly going on to the next phase of “Law of the River” negotiations, Interior is hitting the “pause” button for a year long review of how the current river rules are working.

Speaking on the day’s final session, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt emphasized some interesting points, including the need for the next round of “Law of the River” negotiations to include Native American and environmental NGO interests. An Interior Secretary CRWUA speech is about signalling – that was a particularly important signal. How it translates into action remains to be seen, but the marker has been very publicly placed on the board.

As I think back to book two in “the series”, about how the network functions both formally and informally, I’m intrigued by the way the pause creates some space for informal discussions about what folks want the next round of rule discussions to look like and include.

Where are the fountains?

As has become my December tradition, I’m in a Las Vegas hotel room preparing for this year’s meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association/finishing up grading my University of New Mexico Water Resources students’ final papers for the just-finished semester.

This year’s class – our introductory course for graduate students in our Masters of Water Resource program – focused on “The Value of Water in Alternative Uses”. That’s the title of a 1950s-era study attempting to put valuation numbers on New Mexico’s transbasin diversion of Colorado River water, which was then in the just-being-cooked-up stage. We used the paper as a jumping off point for a lot of discussion about how we use water, and how we might use it differently, and how we decided about such things.

Our students did some terrific work exploring the questions in ways that really stretched all of us:

(Note: If you like to think about such things, we’re accepting applications for fall 2020!)

One of the things we’ll be talking about in the CRWUA panel I’m moderating Thursday is the question of how we incorporate values and interests and communities that have traditionally been left out of water management decision making. That question was at the heart of the work our students did this year to such good effect.

We’re saddled with institutions (and by this I mean both the more traditional sense of agencies and actors, but also the “institutionalists'” sense of the underlying rules themselves) developed around other dominant values that aren’t so good at incorporating new or evolving ones.

The UNM water students did a great job of thinking and talking about what sort of new institutions we might need to incorporate the values they wanted to think about. It’ll be interesting to see how this year’s CRWUA feels when I approach it with that in mind.

Maybe that’s what my next book should be about.

So happy to be a part of this.

Preparing for a panel I’ll be moderating at next week’s Colorado River Water Users Association meeting on the next steps in negotiating river management rules, I went back to a similar panel held last summer at the University of Colorado’s Getches-Wilkinson Center. (the session starts at around 3:23:00 here)

Lake Mead’s “bathtub ring”

John Entsminger of the Southern Nevada Water Authority offered a concise summary of the questions to be resolved (John’s comments, short and worth a listen, begin at about the ~3:34:00 point on the video linked above). Among them:

John’s list includes other bits as well (those interested in what happens next on the river are encouraged to watch the video). But the three bullets are important because there are some folks who are beginning to argue for a litigation approach. Clearly, the argument goes, a proper interpretation of the Law of the River favors “us” on this important question (where all values of “us” have a legal argument for why they will win such a dispute).*

Eric Kuhn and I, in the conclusion of our new book Science be Dammed, think such litigation is unlikely because the principals understand what a terrible idea it would be:

In many ways, the basin states are in a similar position to that of the late 1920s. In 1927, six states chose to continue the ratification process of the imperfect compact they had negotiated rather than reopening the negotiations to appease Arizona and face an unknown future. One of the more likely outcomes was a future without a compact, an unacceptable situation to all of the states but Arizona. Today, the choices are to continue with the 1922 compact as written, with its embedded flaws but open to broad interpretation by the parties, or to engage in major litigation at the United States Supreme Court. The outcomes of litigation could include a future without a compact, a future where the compact has been so narrowly interpreted limiting future cooperative and innovative solutions, or even a future where the river is “federalized” far more than it is today.10 All of those are unacceptable to most, if not all, of the basin states. This means that while litigation is always possible, the inherent risks and ensuing chaos are so great that its chances are much diminished.

For those attending CRWUA, the panel will be at 11 a.m. Thursday. John Entsminger will be one of the panelists, along with

* To be clear, because on re-reading after posting I saw how this could be misinterpreted, John Entsminger wasn’t arguing for a litigation approach at all. He was merely pointing out the unresolved legal questions.