on a bridge, looking down

When you cross a bridge, Craig Childs said at an American Rivers gathering in Santa Fe Friday evening, stop, and look down.

A couple of llamas stared in what I imagine was puzzlement this morning as I dropped my bike and walked out onto the planks bridging one of the irrigation ditches in Albuquerque’s South Valley. Today is my 60th birthday, and I took a long morning bike ride that (metaphor alert) included a lot of stopping on bridges and looking down.

for example, a llama pasture

This is a common feature of the valley ditches – a control structure that can be used to raise the water level to reach irrigation turnouts to divert water into, for example, a llama pasture. This particular ditch is nameless to me, part of the complex system through which the Rio Grande splays out across Albuquerque’s valley floor to irrigate, for example, llama pastures.

Sitting on a panel next to Craig Friday was humbling and a little intimidating. When I was first starting to write what became Water is For Fighting Over, floundering to find a voice, I visited Mesa, Arizona, and this 2007 High Country News Piece of Craig’s:

Phoenix seems either on the verge of unparalleled success or catastrophic failure. At this point, it might be hard to tell the difference between the two.

On Mesa’s mesa you can see the remnants of old Hohokam canals, and I lingered at a modern water drop from one of the Salt River Project concrete behemoths into some of the remnant citrus groves up against the now-mostly-dry Salt River’s bed.

What was quite literally the first draft I wrote was voiced in response to Craig’s piece, and I set out to try to answer the question he had posed – about Phoenix and all of the West. Which are we on the verge of?

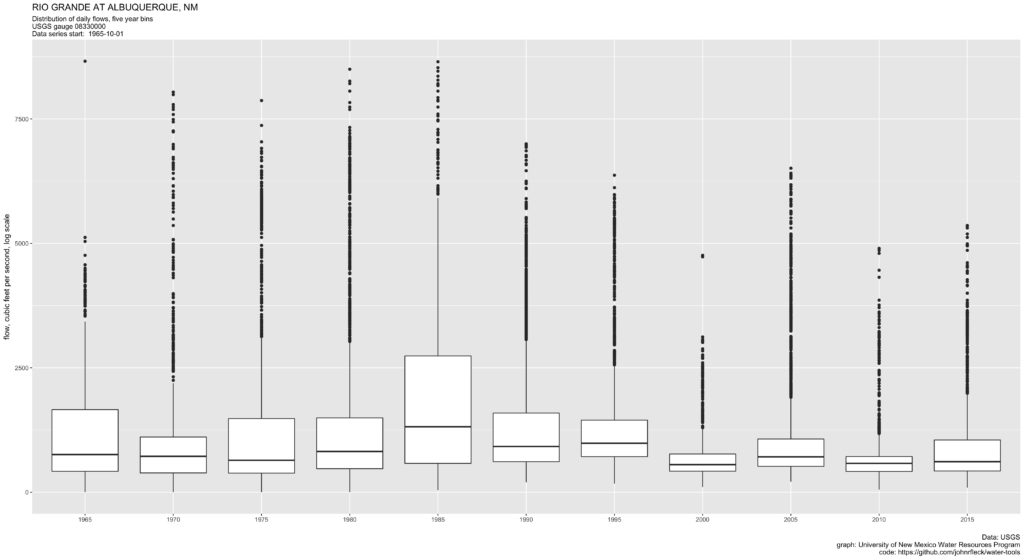

I am not the poet, my gifts if I have them more technocratic. As I carried out Craig’s advice this morning (“When you cross a bridge, stop, and look down….”), I tried to smell the river. (“My earliest memory is the smell of water in the desert,” Childs has written.) I feel prosaic and not at all the poet I imagined I would become when, as a substitute for smell, I stand on the Central Avenue Bridge and look up the Rio Grande’s flow on my iPhone. (5,050 cubic feet per second, the highest flow on my birthday since 1993.)

But as I cross over into my 61st year (metaphor alert) I am comfortable with what I see beneath the bridge, the voice I have finally found.