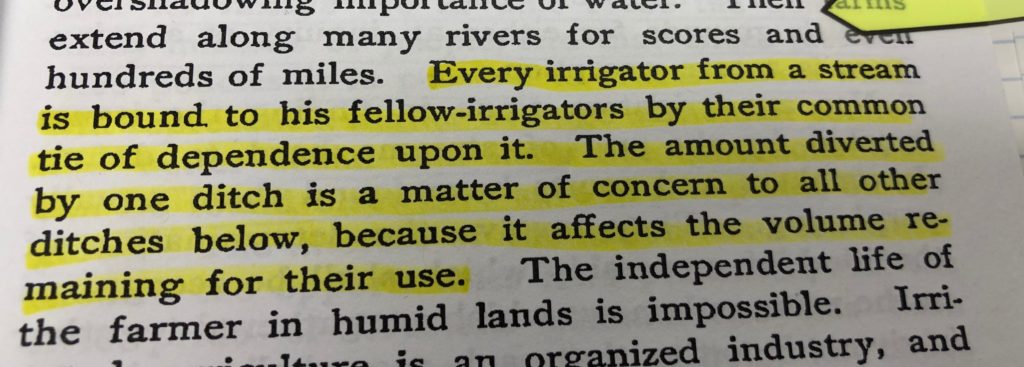

Mead, Elwood. (1903). Irrigation Institutions.

The tiny fragility of Hoover Dam

Looking for art for the new book, I ran across the above picture from the amazing Library of Congress collection of Carol Highsmith’s work. Hoover Dam as cultural icon is big and muscular, which is by design and also a function of the fact that it’s hard to get back and see the dam in context. Most pictures are taken from up close, and from that vantage point it really does look big and muscular.

But if you get back a bit to see its context, it looks tiny, and fragile. Which is a nice metaphor.

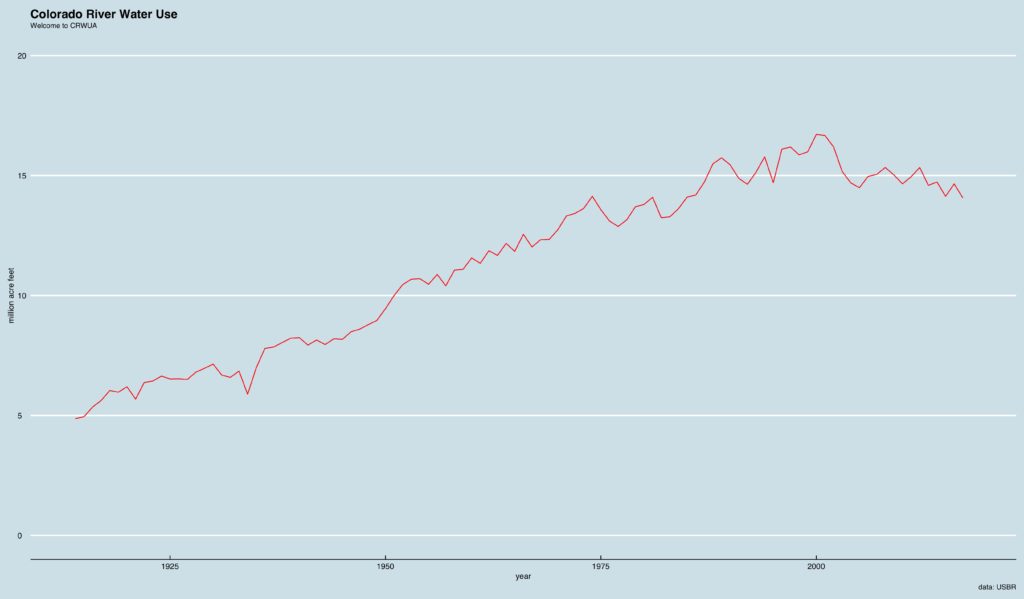

Colorado River water use keeps dropping

New data from the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation shows that total 2017 water use in the basin – 14.07 million acre feet – was the lowest since 1984.

The total here includes estimated consumptive use in the Upper Basin, Lower Basin, Mexico, plus reservoir evaporation and estimated evapotranspiration by native vegetation.

Another Arizona Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan sticking point?

A letter this afternoon from Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke to Central Arizona Project board members, also circulated to Arizona’s Drought Contingency Plan Steering Committee, suggests another hangup in Arizona’s efforts to agree on a plan to reduce its Colorado River water use. It involves the distinction between using water from on-river water users versus contributions from users in central Arizona, in regard to a proposal from CAP board member Karen Cesare:

Full letter is here.

1078.32

I think (?) there’s an Arizona Colorado River deal? Episode II

I’m moderating a panel on the Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan at this year’s meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association in Las Vegas (NV) in a couple of weeks. What shall we talk about?

Arizona’s water agencies, cities, farmers and tribes haven’t quite sealed a Colorado River deal. But they’re getting closer.

The outline of a new compromise proposal emerged this week and was presented at a meeting on Thursday. The plan would help Arizona join in a proposed three-state Drought Contingency Plan by spreading the impacts of the water cutbacks, providing “mitigation” water to farmers in central Arizona while paying compensation to other entities that would contribute water.

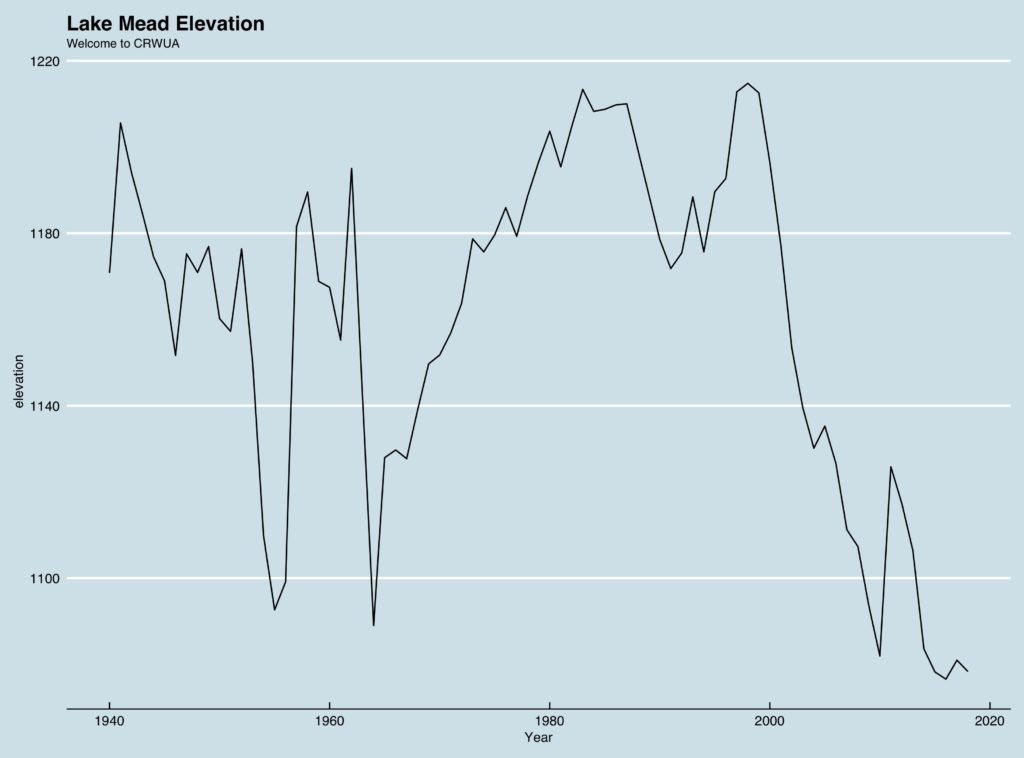

That’s the Arizona Republic’s Ian James on the latest in Arizona’s struggle to find a way to scale back its water use as Lake Mead drops.

Here’s some scene-setting data as the Colorado River brain trust prepares to converge on Caesar’s Palace:

- U.S. Lower Basin use is currently forecast to end 2018 at 7.13 million acre feet, below the Arizona-California-Nevada allotment of 7.5maf. Yay conservation! (source pdf)

- Upper Basin deliveries from Lake Powell are on track at 9 million acre feet this year, way above the 8.23maf “required” (lawyers don’t @ me) under the Colorado River Compact. Yay bonus water!

- Lake Mead is still 2.5 feet lower than last year at this time. Boo overallocation!

See you in Vegas.

I think (?) there’s an Arizona Colorado River deal?

Update: via Ian James from the Arizona Republic, here are the slides for today’s meeting.

Previously: With the announcement of a meeting this afternoon of Arizona’s Lower Basin Drought Contingency Plan steering committee, it appears we have the general shape of an agreement to settle the thorny issue of how to reduce Arizona’s use of Colorado River water.

Not a lot of details yet, but it appears that

- Pinal County farmers will get 595,000 acre feet of mitigation water over the next three years

- Pinal County farmers will get federal help to drill a bunch of wells to advance their efforts to replace Colorado River water with groundwate

- The Gila River Indian Community is on board, and will provide some of the replacement water needed to keep Lake Mead whole

- The Colorado River Indian Tribes may be also providing water to help prop up Mead

- The cities seem to be on board

With those three key pieces – GRIC/CRIT, cities, and Pinal County farmers – we seem to have the necessary agreement for a deal. But I have been wrong about Arizona before.

Not sure if the meeting will be livestreamed, and I’m in Albuquerque with a day job, so I’d be ever so appreciative if folks either in the comments here or on the twitters (#ColoradoRiver or the far less poetic #CoRiver) would add what they know.

the ghosts of water “resources”

Driving in a pickup down a ditchbank on Albuquerque’s valley floor some years ago, Joey Trujillo pointed off to the west, to a line of trees snaking away into what is now a tony suburban neighborhood. It was the neighborhood we now call “Dietz Farm”, named after the Dietz family, affluent interlopers from the east who came to the area during the early decades of the 20th century. Like much of that era in Albuquerque’s history, the people who had the land before the Dietz’s have been erased, but the line of trees has not.

It was a late winter day. Joey was the head ditchrider for the valley, the people who keep the water flowing through the network of irrigation canals that have been here “forever”. I was watching as Joey’s crew carried out a version of a seasonal ritual that dates in this part of the valley to at least 1706, bringing the first water of spring to the valley floor. I say “at least”, because on the old irrigation system inventories maintained by the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, there are a bunch of ditches with a 1706 date attached. The implication – this is not the date the ditches first ran, but rather our first surviving inventory of their presence and use.

Walk or ride your bike down the ditchbanks today, and you’ll see modern amenities, as in the concrete intervention in the picture above, often needed to get the old ditches under roadways. You’ll see gates to meter and measure the water’s flow, aptly called “control structures”. But the ditches often still follow routes laid out centuries ago. They are lined with trees tapping into the water seeping into the shallow aquifer from their unlined sides and bottoms. And if you look closely, you can still see the lines of trees left behind when old laterals were abandoned in succeeding waves of suburban development.

I am grateful to the geographer Jeremy Schmidt, who in his fascinating book Water: Abundance, Scarcity, and Security in the Age of Humanity introduced me to the work and ideas of William John McGee, one of the 19th century “naturalists” who, alongside the likes of John Wesley Powell and Gifford Pinchot, framed a bunch of stuff in ways mostly unexamined by me. Until I’m forced to examine them.

I’m in the midst of three projects right now that are converging simultaneously on the questions raised by McGee and Joey Trujillo’s line of trees stretching out through that Dietz Farm neighborhood. The first is the book I’m writing with Eric Kuhn about the use and misuse of the science of the Colorado River, which has prompted a dive into the question of what we mean by “science”. The second is a University of New Mexico project focused on thinking about the “Grand Challenge” of sustainable water. The third is my endless delight in the ideas my students bring to me, in particular a group of students with fresh ideas about what the water problem is that we’re trying to solve. (Wisely, these students are not leaving it to Prof. Fleck to define the problem.)

McGee was secretary of the U.S. Inland Waterways Commission, appointed to the position by Teddy Roosevelt, when he wrote this in a 1909 essay called “Water as a Resource”:

Now is the time of conquest over nature in practical sense, of panurgy in philosophic sense – the day of prophecy made perfect in predetermined accomplishment.

“Panurgy” stumped me, and given the context I’m not sure McGee intended the sense I found when I turned to the Oxford English Dictionary for help: “Interference or mischief-making in all matters; knavery.” But the OED definition adds a nice flavor to our attempt to look back with our 21st century eyes to get a feel for what McGee was on about:

No more significant advance has been made in our history than that of the last year or two in which our waters have come to be considered as a resource – one definitely limited in quantity, yet susceptible of conservation and of increased beneficence through wise utilization. The conquest of nature, which began with progressive control of the soil and its products and passed to the minerals, is now extending to the waters on, above and beneath the surface. The conquest will not be complete until these waters are brought under complete control.

When I took over two years ago as director of the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources Program, one of my colleagues stopped by to congratulate me, talk about our shared passion for water, and to make a longstanding request: Could I please drop “Resources” from my program’s name? Putting water into the conceptual “resource” box constrains our thinking about it, she argued, in ways that are an injustice to the many other conceptual frames that suggest values for its own sake rather than the “conquest” envisioned by McGee a century ago.

I didn’t change the program’s name. But the seed planted has been growing, which I’m guessing was her point.

The university’s “Grand Challenge” risks putting water into the “resource” box again, but after two years teaching and working with my amazing watery colleagues – geographers, landscape architects, historians, economists, hydrologists, engineers, political scientists, artists – I’m beginning to get a feel for the plasticity required to navigate the interdisciplinary nature of thinking about water.

I’m particularly indebted to one of my smart students who’s thinking really hard about those valley ditches. They are rooted in a long tradition of resource exploitation in the style of McGee, turning water out of the Rio Grande and across the otherwise parched spring and summer valley floor, a “conquest of nature” in the 1600s as sure as McGee’s early 20th century conception.

We can ship soy milk in from Iowa now. Those ditches thread through the valley floor in a way no longer needed for the conquest. But they have become something far more than a “resource” in the sense McGee was talking about, something much closer to the broader conception my faculty colleague was getting at when she came to me asking that “resource” be dropped from my program’s name.

Joey Trujillo died a few years ago, but it seems reasonable that the ditches he so carefully helped tend will be here for a long time yet.

20 years and 5,767 posts on, a thank you note to Inkstain readers

Thanks, y’all, for 20 years of stopping by to read stuff here.

There’s a game we used to play back in the day called “googlewhack”. It involved searching for a two-word phrase that was unique – that had never before been catalogued in Google’s even-then-vast archive of humanity’s digital use of written language. We’d stick it in a blog post, claiming the phrase, and revel in the strange wonder of the diversity of language.

Thus it was that in late 2003, I came to own “orbitally aardvark”. Remarkably, I still do. Perhaps not so remarkably? It’s admittedly hard to imagine a sentence in which the phrase might do actual useful work.

On the occasion of Inkstain’s 20th birthday – Rob Browman and I registered the domain name, according to ICANN records, on Nov. 18, 1998 – we’ve been waxing nostalgic.

Rob, always the photographer even as his skills have wandered through the evolving communication technologies of the last few decades, found a wonderful picture of the Albuquerque Journal’s web team from around that time. On film.

It was a crazy wonderful time of experimentation, naive optimism with little adult supervision. We went all in on the 50th anniversary of the Roswell Incident, and Donn has lovingly curated the Comet Hale-Bopp page through all the server moves that have followed.

Inkstain was nothing more than a little side project then, a spare Unix box wired up to a fledgling Internet so we could experiment, mostly writing bad Perl code, one further step removed from adult supervision. Once we got the domain name registered, we compiled an Apache web server, and Inkstain.net was born.

Its name came from our profession. We were inkstained wretches, passionate about the task of, and opportunity presented by, the privilege of newspapering. We were on fire with the wonderful new opportunities the Internet offered for us to communicate with new people in new ways.

Most of what we did happened on the Journal’s web site – my first blog, Roswell, Comet Hale-Bopp, the news. But we didn’t really want to prank, at least not too much, on the Journal’s production server.

The first prank happened the day after we got the web server up and running. Within minutes, we started getting traffic. Puzzled, we looked at our newfangled logs, learned how to read the “http referer”, and found incoming traffic from Spanish Altavista. (Altavista was a “search engine”.) A bit more sleuthing, and we found that prior to our claiming it, the domain name “inkstain.net” had been registered to a porn site.

This seemed, to us, an opportunity. Audience! Rather than giving the disappointed wankers a standard “404” error page, we offered this. It doesn’t seem to fully work any more – the NSA has changed its web address, I think. But in its day, as our first Internet prank, it seemed a doorway to something special.

Thus began a pattern. The serious newsy experimentation happened on the Journal’s web site, while we played on Inkstain. Scott Smallwood, now at the Chronicle of Higher Education, built a web site devoted to narrative journalism. Rob and others began building photo sites, stuff done outside their journalism work. And in the spring of 2003, I started writing this blog.

I’d already been blogging in several other places and ways. But each of them fell under someone else’s intellectual architecture. As I explained in the first post, I wanted something that was all mine:

By no longer hiding behind the skirts of an existing publisher, I lose built-in audiences, but that seems fine. I’ll still do the other blogs when my whim suits their audience (and in the case of ABQJournal, I get paid for that, which still amazes me). But if Tim Berners-Lee’s original idea of the web as a medium for both reading and writing has any meaning at all, this is it, so my Inkstain web site must reflect that.

By that point in my life, I’d already been typing strings of words professionally for more than 20 years. But it was here, beyond the constraints of any particular publisher or platform or audience, that in partnership with you I found my own voice.

It was here, ten years ago next month, that I began chronicling the decline of the inkstained wretches. There is irony here that needs no further comment, but it was with those “elephant diaries” that I finally felt like I had found a voice that was fully mine.

I also wrote what I judge my finest post:

It is frequently suggested that there are important parallels between the changing business models of the news and music industries, and that there is much we can learn from one another.

I am currently brainstorming ways to get someone to pay me to perform journalism in bars.

I turned my attention to water, something I’d been fascinated with since the beginnings of my journalistic career. Here on Inkstain I could write about it loudly and often, sketching out the ideas that led to a book, which led to a position on the faculty of the University of New Mexico standing before students yammering about water, which it occurs to me is not that far from my suggested business model of performing journalism in bars.

None of this would have worked without you. A writer without readers is, if not nothing, at the very least something very different than what I would be.

So, with this, my 5,767th Inkstain post, I offer my thanks.

Bruce Babbitt: Pinal County Farmers and CAP Risk Setting Off a Colorado River Water War

Wow.

Bruce Babbitt, former Arizona governor and Secretary of the Interior, has a striking op-ed in tomorrow’s Arizona Republic placing the blame for Arizona’s current Colorado River failures squarely on Pinal County farmers and the leadership of the Central Arizona Project.

Ultimately the responsibility for approving Arizona’s part of the critical Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan lies with the Arizona state legislature. But the two groups now stand in the way of that, Babbitt argues.

Behind this legislative impasse are two groups threatening to block ratification.

The first is the Central Arizona Water Conservation District (CAWCD), a local elected body that distributes our Colorado River water throughout central Arizona.

CAWCD is now reaching beyond its proper role by attempting to intervene in the interstate Colorado River negotiations….

The second threat to legislative ratification of the DCP comes from the Maricopa Stanfield Irrigation and Drainage District, the Central Arizona Irrigation District and several other agricultural districts located in Pinal County….

In exchange for giving up long-term rights to Colorado River water and pumping more local groundwater, the districts bargained for and received heavily subsidized Colorado River rates to be paid for by property taxes levied on landowners in Phoenix, Tucson and throughout central Arizona.

Now they’re trying to wriggle out of that bargain in a way that threatens the entire Colorado River Basin, Babbitt argues.

As this controversy drags on in successive legislative sessions some are asking, “Why the urgency? Does it really matter that it goes unresolved?”

It matters a lot. If the Drought Contingency Plan is not ratified soon California and the other Basin states may decide to proceed without us. That could be the beginning of another Colorado River water war.

Arizona has blundered into Colorado River wars in the past, and we usually lose. We must not go that way again. It is up to the Legislature and Gov. Doug Ducey to promptly ratify the Drought Contingency Plan as negotiated by the Department of Water Resources.