Up close with Lake Mead’s bathtub ring

LAS VEGAS – With Commissioner of Reclamation Brenda Burman’s ultimatum to the Colorado River Basin States at the just-completed Colorado River Water Users Association meeting in Las Vegas, it seems we’re going to get a Drought Contingency Plan, or something very much like it, in 2019.

This could be very messy, but it suggests that either voluntarily (through interstate agreement) or imposed by the feds, we’ll have new shortage guidelines in place by 2020 to slow the decline of Lake Mead. While the messiness will occupy a lot of our attention over the next year, we shouldn’t lose site sight of what comes next. DCP is a bridge, providing some stability while we launch the round of discussions needed to shore up the Law of the River.

Importantly, however, the messiness of the DCP discussions have provided some useful new clarity about what will be needed to solve the longer term problems, and also are building some of the tools we’ll need to solve them.

In broad terms, I see two big long term problems.

Long Term Problem One: Malfeasance of the Past

The malfeasance of the Law of the River’s framers in ignoring science (the subject of the new book Eric Kuhn and I are writing) left us with a web of water allocation rules based on a fictionally large supply of water. Part of the malfeasance was a failure to build tools to help manage downside risk, to cope with reallocation if and when the supply wasn’t that large.

Now, whether through ignorance or, again, malfeasance, we now have communities that have come to expect that fictionally large supply, and few rules to determine who gets less, and how much.

Long Term Problem Two: Climate Change

So yeah, climate change means less water. That makes solving Problem One harder.

Short Term: The Ultimatum

The basin leadership came at us with a crisp talking point that I heard over and over again at CRWUA: “Close isn’t done.” Yes we’re close to a DCP, but we’ve been that way for a while. The longer we wait without getting to “done”, the bigger the risk gets.

Burman signaled that the federal government’s patience has run out. She gave the states of the Colorado River Basin until Jan. 31 to sign off on the DCP. If the deal’s not done, Burman said, the federal government will begin steps to take action of its own. “We will act if needed to protect this basin,” Burman said during an extraordinary Thursday morning address to a packed Caesar’s Palace ballroom.

This raises the question of “the secretary’s discretion” – under what conditions can the U.S. Secretary of Interior step in and reduce deliveries from Lake Mead under its Law of the River authorities? It is a huge unresolved legal question, and we now have the prospect of testing its boundaries in 2019.

Five of the seven Colorado River Basin states have essentially committed their states to the DCP, California is largely there save some last-minute hesitation regarding the perennial and largely unsettled question of mitigating impacts on the Salton Sea. Once Arizona’s ready, there’s little question California will fall in line. But Arizona? There was an unusually large contingent of Arizonans at CRWUA. I hope they noticed us all tapping our feet impatiently, arms folded, glaring at them.

Short Term: The Other Ultimatum

Meanwhile the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has increased the pressure with an ultimatum of its own. Absent a DCP, Met is at risk under the current rules of having its banked water stranded in Lake Mead. DCP would relax those restrictions, but without a DCP, Met has made clear it has no choice but begin taking that water out beginning in January. (Daniel Rothberg explains all this here.) This means Lake Mead drops faster, increasing everyone’s risk, but especially Arizona’s. (Tapping foot, glaring, arms crossed, at Arizona.)

Short Term: DCP or Something Like It

If there’s no DCP come Jan. 31, Reclamation will begin a process aimed at coming up by summer with rules needed to slow the decline of Lake Mead. Given that the basic framework of DCP has general agreement, it’s easy to imagine that the Reclamation plan would not be that different:

- some sort of legal widget to allow Met to leave its banked water in Lake Mead without the risk of having it stranded

- deeper cuts, and sooner, as Mead drops

Short Term: The next few months

In the next few months, the chaos resulting from the lack of DCP and the hustle to either finish it or cobble together a Reclamation-imposed alternative will seem all-consuming.

Long Term: Renegotiating the Interim Guidelines

Given the number of brain cells being burned to exhaustion by the DCP process, one argument over the last year among basin insiders is the suggestion that we should just give up, let the current rules run while we begin the next step – renegotiation of what are called the “Interim Guidelines”.

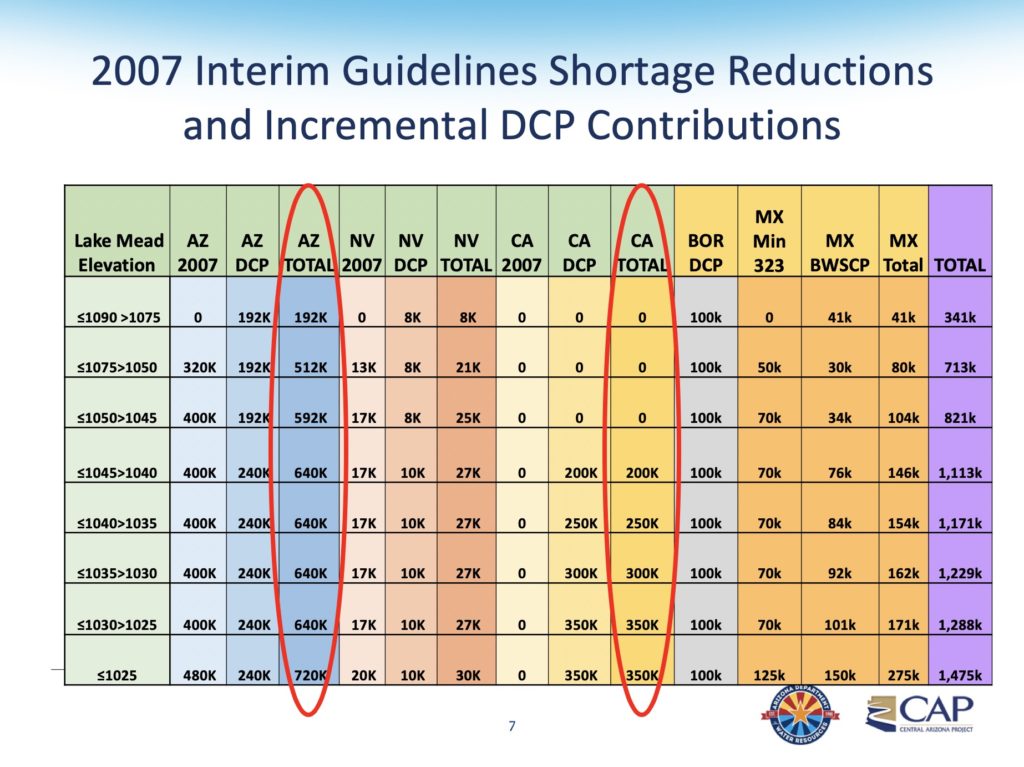

Negotiated from 2005-2007, the Interim Guidelines are the current rule set for managing Lake Mead and Lake Powell. They govern how much water is released from Powell, and when. They govern the depth of cuts taken by Arizona and Nevada as Lake Mead drops. That famous “Arizona faces a COLORADO RIVER SHORTAGE when Mead hits elevation 1,075” rule? That’s the Interim Guidelines.

The guidelines expire in 2026, and also include a provision requiring renegotiation to begin in 2020. The fear is that those negotiations would be exponentially harder if you had no DCP and a plummeting Lake Mead.

Speaking to the Arizona Republic’s Ian James, Arizona’s Sharon Megdal put it this way:

“We’ve got to get this done so we’re prepared in 2020 to start renegotiating the shortage-sharing guidelines, and that’s really the future — a future of less water use,” Megdal said.

“What’s happening in the environment is happening in the environment, and we have to adapt to that,” Megdal said. “We’ve got to plan for less water.”

There are a bunch of thorny unresolved issues in the current rule set that will have to be sorted – issues that, because of the overallocation of the river, would be hard no matter what, but that are made worse by climate change.

- How might climate change alter the interpretation of Article III(d) of the Colorado River Compact, which is typically interpreted as requiring the Upper Basin states to deliver 75 million acre feet of water every ten years? The compact doesn’t call it a delivery obligation, but rather an obligation not to deplete the river’s flow. What if it’s climate change depleting the river’s flow, rather than Upper Basin water use?

- What is the Upper Basin’s share of the U.S. obligation under Article III(c) to Mexico?

- How much water can be held in Upper Basin reservoirs as a hedge against dry years under section 602(a) of the 1968 Colorado River Basin Project Act?

On all these points and many more unsettled issues, everyone has clever lawyers with an interpretation that favors their interests. But clever lawyering won’t conjure water, which is the key to what Megdal is saying. We’ve got to plan for less water. DCP recognizes that, but the difficulties in coming to final agreement on the DCP suggests not all the basin’s water users grasp the new reality.

That, I think, is DCP’s most important lesson.

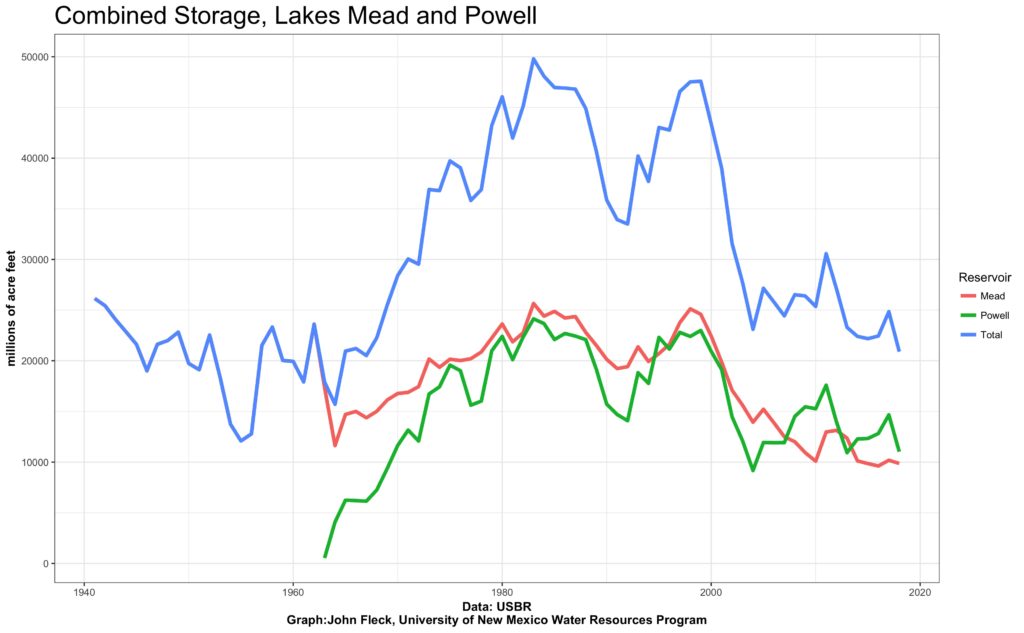

By the numbers, Lake Mead began 2019 at elevation 1,081.47 feet above sea level, down a foot in 2018. This comes in spite of yet another Upper Basin release of 9 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam last year, an extra 770,000 acre feet above the 8.23 million acre feet the Lower Basin can rightly expect under the Law of the River. Since 2000, the Upper Basin has delivered an excess of 9.8 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam above and beyond the 8.23 million acre feet expected every year under the current interpretation of the Law of the River. In that time, the level of Lake Mead has declined 115 feet.

By the numbers, Lake Mead began 2019 at elevation 1,081.47 feet above sea level, down a foot in 2018. This comes in spite of yet another Upper Basin release of 9 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam last year, an extra 770,000 acre feet above the 8.23 million acre feet the Lower Basin can rightly expect under the Law of the River. Since 2000, the Upper Basin has delivered an excess of 9.8 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam above and beyond the 8.23 million acre feet expected every year under the current interpretation of the Law of the River. In that time, the level of Lake Mead has declined 115 feet.