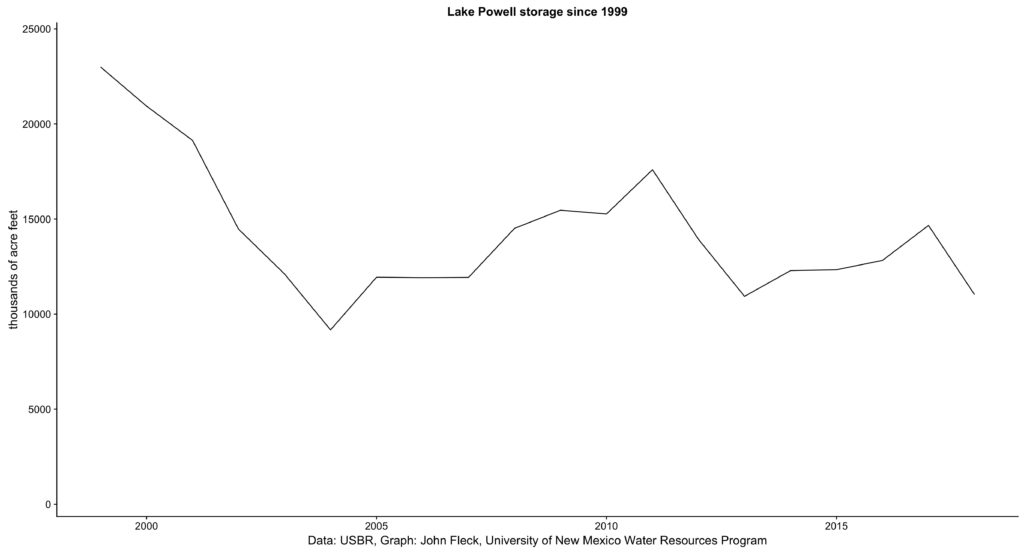

Here is some data about Lake Powell, the big Colorado River reservoir straddling the Arizona-Utah border.

- Since 2005, the average estimated “natural flow” of the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry has been 13.5 million acre feet per year, well below the 14.8maf average since 1906.

- Since 2005, releases from Lake Powell have exceeded the Upper Basin’s Colorado River Compact and Mexican treaty obligations by 9.4maf.

- So despite the fact that it’s been dry, we Upper Basin residents have had enough extra to deliver a bunch of “bonus water” to downstream water users.

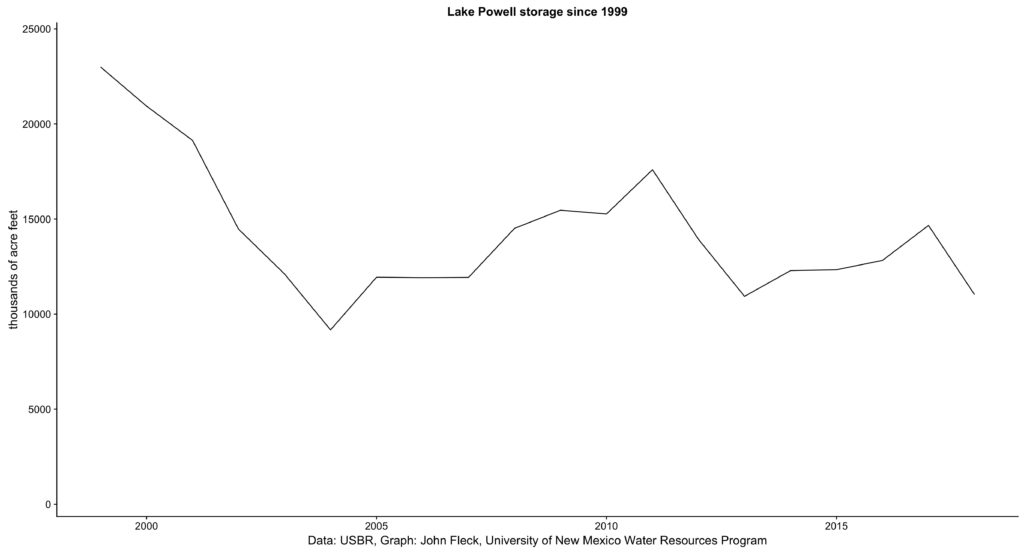

- Since 2005, the total volume of storage in Lake Powell has risen, from 9.169 million acre feet at the end of 2004 to 11.028 million acre feet at the end of 2018.

- So despite being dry, and delivering extra water downstream, Lake Powell’s elevation has been relatively stable.

This is straightforward empirical stuff.

Brian Maffly has a great piece in the Salt Lake Tribune about the challenges of Colorado River management, with a focus on Lake Powell.

But Maffly weakens an otherwise excellent survey of the river’s issues with the alarmist assertion that “without a change in how the Colorado River is managed, Lake Powell is headed toward becoming a ‘dead pool.'”

It is important when doing journalism about phenomena over time (and any other sort of analysis) to choose periods of record that accurately capture the thing you’re trying to understand and explain. Maffly, and the sources on whom he relied for the story, have cherrypicked a time window that supports the “OMG POWELL DOOMED” argument, but that is misleading.

In support of his argument, Maffly notes that Powell “has shed an average of 155 billion gallons a year over the past two decades.” That is correct, but it’s a troubling choice of time frame. Since 2000, Maffly writes, Lake Powell “has been steadily dropping.” This is false.

The entire loss Maffly describes happened during the first years of the 21st century, the driest five-year stretch on record. Yowza, Lake Powell dropped a lot during the drought!

From 2005 to the present, Lake Powell’s elevation has been relatively stable, not steadily dropping.

Lake Powell storage since the turn of the century

It certainly would be correct, and is important to note, that a repeat of the drought of the early ’00s would be disastrous. Absent changes in management, it would lead us to dead pool. It is important to have policies in place that are ready for that. Increased withdrawals from the basin increase the risk should that happen. But the years that followed the drought of the early ’00s, in which Lake Powell’s levels have been stable despite a river flow depleted by climate change and the crazy policies that continue to ensure excess downstream deliveries, also are important if we’re to assess the impact of current Colorado River operating policies on the risk of Lake Powell reaching dead pool.

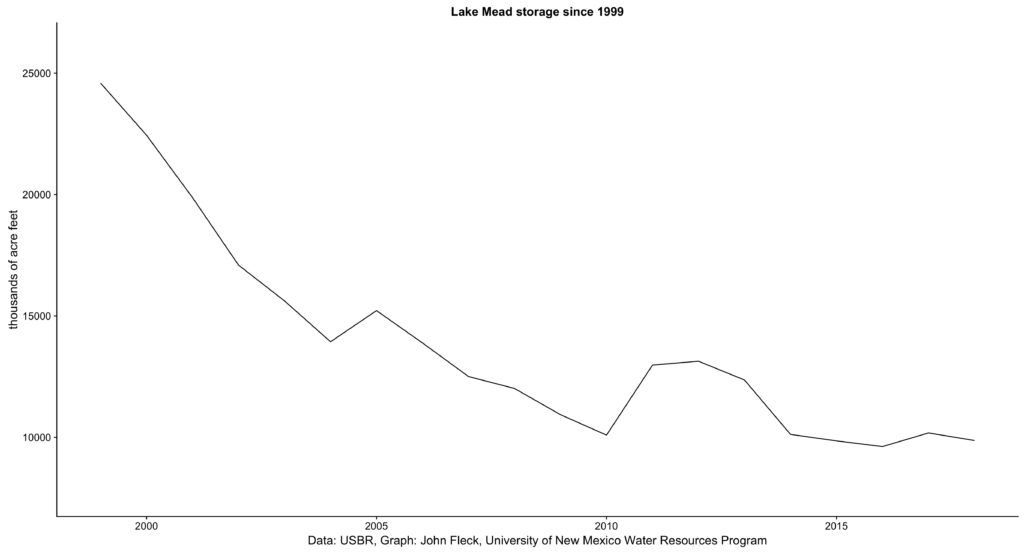

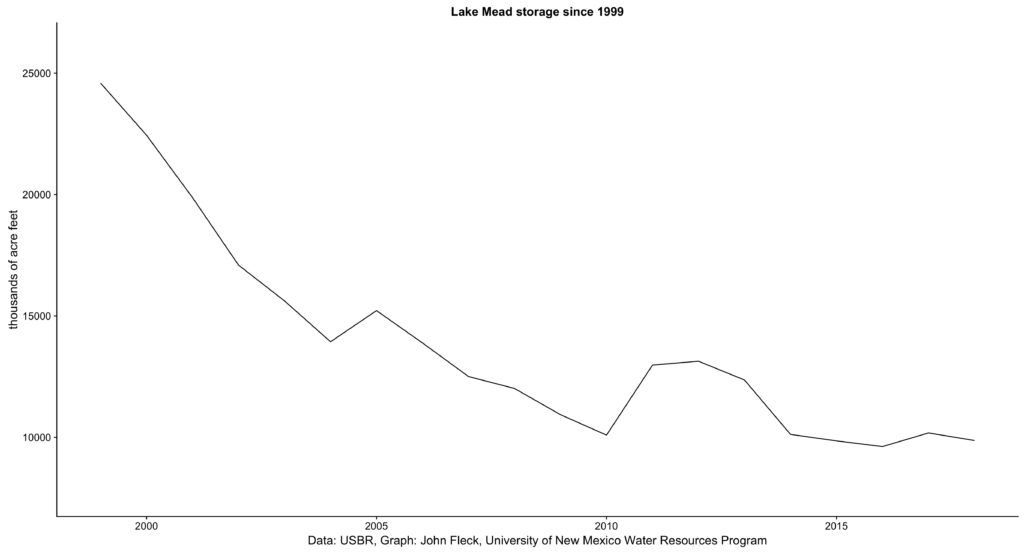

The reservoir that seems to be headed far more inexorably toward disaster is Mead, not Powell. That’s a lot closer to what I imagine when I hear “steadily dropping”. Remember that Mead is declining despite deliveries since 2000 of more than 9 million acre feet above the Compact-Mexico obligation of 8.23maf per year.

Lake Mead storage since the turn of the century

To be clear, I believe the Colorado River faces serious challenges. I agree with Doug Kenney, who told Maffly, “At some point, you can’t ignore reality anymore, and the reality is we need to use a lot less water in the Colorado Basin.” Yup. Doug’s right. This includes the Upper Basin. The Lake Powell pipeline and other efforts to take more water from the system seem ill-advised, guaranteed to increase the risk to existing users in both the Upper and Lower basins.

Much of the challenge right now, though, is in the Lower Basin. The ability to maintain Lake Powell’s elevations over the last ten-plus years despite drought and “bonus water” releases from Powell suggests the Upper Basin is in a far better position.

Much of Maffly’s discussion of the overall challenges is excellent. It’s important, especially for Utah water users to hear. But selling that message with “OMG LAKE POWELL DEAD POOL” is at odds with the facts, and undercuts the otherwise important stuff the story has on offer.

A note on data sources: